Global value chains (GVCs) offer new opportunities for SMEs to integrate into the global economy. The benefits of GVC participation depend on the nature of inter-firm linkages and their position in global production networks. The digital transformation is reducing trade costs, increasing SME involvement in trade, and spawning a new breed of born-global enterprises. Nevertheless, trade costs and restrictions remain, which impact SMEs disproportionately. The increasingly complex trading environment requires whole-government approaches to address SME constraints in internationalising, including access to information, skills, technology, finance, trade facilitation, and connectivity.

Challenge

Relative to their weight in the economy and share of employment, SMEs account for only a small proportion of exports (OECD-WB 2015). In most OECD economies, SMEs account for upwards of 95% of all firms, around two-thirds of total employment, and over half of business sector value-added, but their contribution to overall exports is significantly lower – between 20% to 40% for most OECD economies. In most economies, more than 90% of large industrial firms export, compared to 10%-25% of SMEs.

Trade and global value chains (GVCs) create opportunities for SMEs to absorb spill overs of technology and managerial knowledge, broaden and deepen their skillsets, innovate, scale up, and enhance productivity (Lileeva and Trefler 2010; Caliendo and Rossi-Hansberg 2012; Wagner 2012; OECD 2018). International exposure, whether through imports, exports, or foreign direct investment (FDI), frequently goes hand in hand with higher productivity and can be an important driver of employment growth (Wagner 2012). SMEs integrate GVCs as direct exporters (trading), upstream suppliers of exporting firms (supplying), or importers of foreign inputs and technologies (sourcing). They can also partner with multinationals (partnering) or become multinationals themselves (investing) (OECD 2018). The type of SME engagement in GVCs also varies across types and sectors of activity, such as manufacturing and services.

The rise of global value chains (GVCs) and the digital transformation offer new opportunities for SMEs to integrate into the global economy. Greater flexibility and the capacity to customise and differentiate products can give SMEs a competitive advantage in global markets, as they are able to respond rapidly to changing market conditions and shorter product life cycles (OECD 2018).

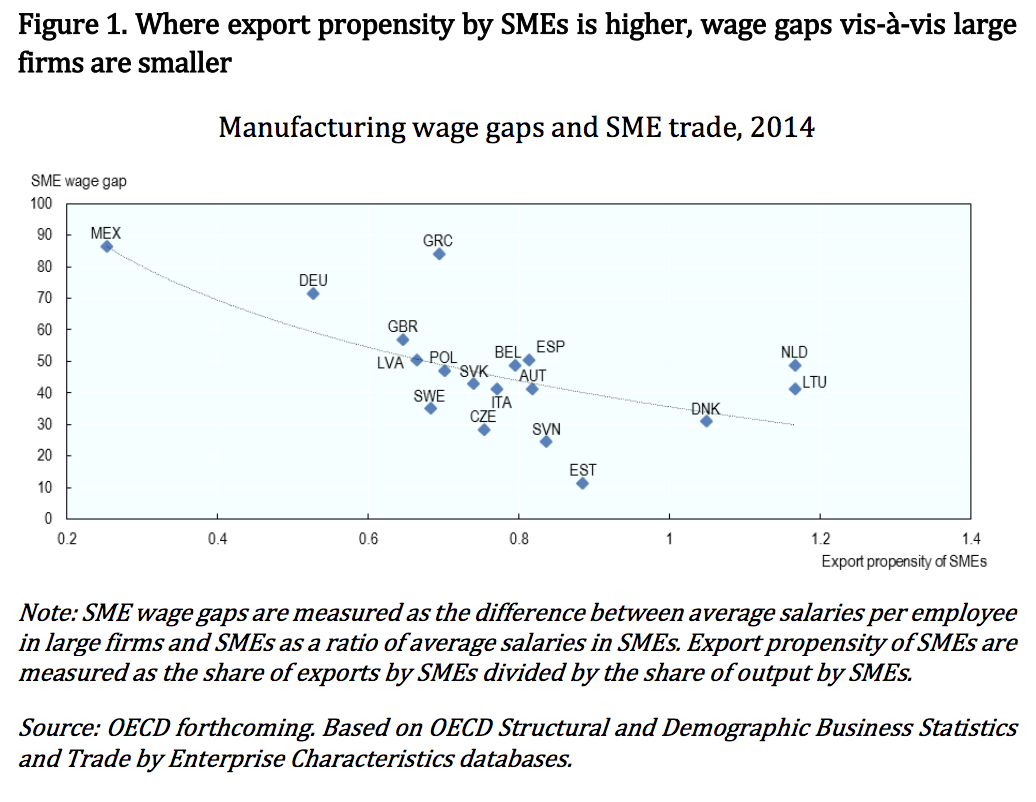

In fact, some niche international markets are dominated by SMEs, and innovative small enterprises are often key partners of larger multinationals in developing new products or serving new markets. For example, in Germany, small- and mid-size companies hold between 70% and 90% of global market share in some specialised manufacturing segments and account for the bulk of the German international trade surplus (OECD 2016; OECD 2018). In addition, in countries where SMEs have a relatively high share of exports, differences in average salaries between SMEs and larger firms are smaller (Figure 1).

However, while trade and investment liberalisation and the digital transformation have contributed to increased cross-border fragmentation, trade costs and restrictions remain and disproportionately affect SMEs.

Engaging in international markets can be expensive, and usually only the most productive firms can afford to do so (Melitz 2003; Bernard et al. 2007). Lacking economies of scale, trading costs represent a higher share of the value of an SMEs’ exports – meaning that they are disproportionately affected by tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade (WTO 2016a). Moreover, the impact of GVCs on SME upscaling and growth is dependent upon the position in the global production network, the quality of infrastructure, the policy environment, and access to strategic resources. In turn, SMEs face considerable challenges in accessing financing for new investments, information, skills, and technology, all of which reduce their international competitiveness and their ability to face trade costs (Jinjarak et al. 2014).

Proposal

Adopting an SME Lens When Considering Efforts to Promote GVCs

Barriers to SME integration into global markets affect SMEs disproportionately, and policy plays a key role in overcoming these barriers. The complex web of global production highlights that a broad range of policies can matter, from services trade to efficient domestic markets.

Global value chains amplify the importance of both goods and services trade policies. Modern production networks rely on two-way flows of imports and exports of goods and services. These intermediate inputs often cross borders multiple times, each time accumulating additional trade costs. These trade costs disproportionately affect SMEs, given their lower revenue base. Although tariffs for many goods are low in advanced economies, substantial barriers to trade in services remain. OECD work on Service Trade Restrictiveness Indicators reveals restrictions on foreign ownership, restrictions on the movement of people (e.g. quotas, stay duration limits), and barriers to competition even amongst advanced economies (OECD 2017a).

For cross-border service exports by SMEs, for example, an average level of services trade-restrictiveness represents the equivalent of an additional 12% tariff relative to large firms (OECD 2015). Establishing an affiliate abroad involves an even wider range of sunk and fixed costs. For a medium-sized firm of EUR 5 million in turnover, selling specialised services through foreign affiliates, the average level of services trade-restrictiveness can be equivalent to an additional 19% tariff compared to large firms. Opening up services markets would thus primarily benefit SMEs. Not just through greater market access, but also by reducing the costs of service inputs which are essential for the international operations of SMEs.

Trade Facilitation

While some trade costs fall, others remain. Goods still incur considerable tothe-border, at-the-border, and behind-the-border costs, underscoring the need for continued efforts to streamline trade facilitation. Promoting policies that streamline border procedures, simplify trade documents, and automate border processes can help (OECD 2015). There is no one-size-fits-all institutional arrangement for countries to implement logistics-related reforms. However, a collective framework that includes the private sector is important for consistent implementation. Canada, China, Finland, Germany, Malaysia, and Morocco have all introduced councils or similar coordination mechanisms for this purpose (OECD-WB 2015). Reform of slow or cumbersome border procedures can cut trading costs by 12%-18%, depending on the country’s level of development (OECD 2015). Trade costs faced by SMEs also depend on applied de minimis thresholds (the value threshold), under which no tariffs or taxes are collected. Above this threshold a tariff must be paid and packages might be delayed for inspection at the border, increasing delivery time.

Putting in Place Competitive Domestic Markets to Foster GVC Participation

Lifting product market regulations encourages innovation and the growth of the most efficient SMEs via increased competition, enhancing their GVC participation. In addition, by providing easier and cheaper access to inputs, reductions in red tape can also lead to gains for downstream firms using these inputs (Abe 2013). But there is scope for further services liberalisation. Reducing barriers to entrepreneurship in the services sectors (such as telecommunications, transport and logistics, and professional services) are particularly important for broader GVC participation (OECD 2017a).

Supporting SMEs to Cope with Diverse Regulations and Standards

The diversity of regulatory standards can be a major barrier for SME integration into GVCs. Technical barriers to trade cover 30% of international trade and more than 60% of agricultural products are affected by sanitary and phytosanitary measures (Nicita and Gourdon 2013). However, standards are far from harmonised across countries, and complying with each destination market’s regulations and standards can require firms to make costly investments in adapting production processes, specific packaging and labelling, or force them to undertake multiple certification processes for the same product (OECD 2013). Providing technical support for SMEs to meet these requirements is therefore important (Gereffi 2018). Furthermore, mutual recognition and convergence of regulatory standards would reduce the burden of compliance for small-scale exporters (OECD-WB 2015).

Fostering SME access to finance for international activity

GVC participation often requires investment in product and process innovation to upgrade technology. It also requires working capital to finance exports and address needs that may arise from the delays between production and payment from foreign customers (WTO 2016b). However, access to finance is a challenge for SMEs and calls for policies that address credit market imperfections and support the broadening of financing instruments available to SMEs in line with the G20/OECD High-level Principles on SME Financing (G20/OECD 2015). This includes export credit guarantees and measures to develop supply chain finance (OECD-WB 2015; BIAC et al. 2016). For instance, in Mexico, the Production Chains Programme launched by NAFIN (the state-owned development bank) allows small suppliers to use their receivables from large buyers to access working capital financing; provides financial training an assistance to SMEs; and eases the interaction between large buyers, SMEs, and financial institutions through an electronic platform (OECD 2015).

Public Support to Overcome Information Barriers related to Business Opportunities, Foreign Product Standards, Trade Procedures and Contact with Potential Buyers/Suppliers

Providing information on rules and regulations, disseminating market information, international trade fairs, or supporting the identification of foreign business partners can help SMEs engage in international activity (European Commission 2010). The opportunity for firms to create networks and conduct exchanges with peers is a key element for international success (Solano Acosta et al. 2018). Spill overs can occur from nearby firms in the same industry and exporting to the same market and hiring workers with experience of that export market (Choquette and Meinen 2015).

However, many SMEs are not aware of the support available, not even SMEs that are internationally active (European Commission 2010). This is despite evidence suggesting export promotion agencies (which often provide a range of these information services) have a larger impact on exports by SMEs than larger firms (Cruz 2014). For instance, in Korea, the Export Capacity Enhancing Project (implemented by the Small and Medium Business Administration [SMBA]), offers SMEs a broad range of services, such as education, global market information supply, marketing, market research, strategy consulting, and global brand development. (Kim 2017).

Supporting SME Skill Investments for Internationalization and GVC participation

Upgrading technology and scaling-up production requires skills and organizational capital. Supporting investment in skills is critical, such as via policies that combine high-quality initial education with vocational education and lifelong learning opportunities, initiatives that support SMEs in attracting talent and appropriate skills to undertake international activity (OECD-WB 2015). In Portugal, the “INOV Contacto” programme matches young graduates with companies that seek high-potential human resources aiming for an international career. Programmes that support internal capabilities through training and skills development can also form a key element of the internationalization process of SMEs (OECD 2008). A comprehensive approach to improving SME expertise and strategic capabilities for navigating international markets can be found in programmes that combine training with coaching from consultants or export advisors. This is the case of Denmark’s Vitus programme (launched in 2010) which targets SMEs with particularly high international growth potential, offering counselling and one-year intensive coaching for developing and executing an export strategy.

Fostering Investment in Innovation

Policies that support investment in local innovation, such as through intellectual property protection, R&D fiscal incentives, and university-industry collaborations can play a role in developing SMEs’ capacity to absorb new technologies (OECD forthcoming). Policies that encourage stronger links between firms and research, educational and training institutions can facilitate the knowledge transfers required for upgrading in GVCs. In addition, research collaboration between firms positively impacts the quality of firms’ innovation, especially when spill overs take place with a foreign firm (Iino et al. 2018).

Policies that promote partnerships between SMEs and foreign firms can help develop or transfer technology, products, processes, or management practices (OECD 2008). For instance, in 2017 in Turkey, following the decision by the Ministry of Economy to provide support to the membership of e-commerce websites, the Turkish Exporters’ Assembly signed an agreement with ecommerce platforms Alibaba and Kompass, which is expected to foster SMEs participation in global e-commerce markets and create opportunities for new entrants, as previous experience from other countries shows. In New Zealand, SMEs operating on Alibaba were able to enter foreign markets a low cost and easily obtain market knowledge through business networks. However, online platforms were only the first step, as further internationalization often requires opening a foreign subsidiary and hiring local staff (Jin and Hurd 2018).

Creating a Supportive Domestic and International Operating Environment for SMEs through a Whole-of-Government Approach

The increasingly complex trading environment requires a greater focus on domestic whole-of-government approaches (OECD 2018). Many of the constraints that SMEs face in internationalizing relates to access to information, skills, technology, or finance, underscoring the importance of continued action to address them. In terms of trade policy, reducing the cost of importing, through continued liberalisation of goods and services and sustained support for trade facilitation and connectivity, will particularly help SMEs better exploit new opportunities. Improved export competitiveness can be achieved through broader policy measures that recognize the important upstream role played by SMEs. Policies should be adapted to reflect a holistic view of production, especially in sectors which require scale.

Programs that provide greater information to SMEs on new opportunities and help promote linkages and partnerships with larger domestic and international firms can enable SMEs to better exploit their comparative advantage in the production of intermediate goods and services (OECD-INADEM 2018).

SMEs seeking to engage in digital trade require cheap and reliable access to digital networks (OECD forthcoming). This means good physical infrastructure and appropriate regulatory frameworks. Here, restrictions on trade telecommunications services can inflate the cost of access to digital networks, disproportionately affecting SMEs’ ability to benefit from the new opportunities offered by digital trade.

Promoting digital connectivity by increasing the quality of digital infrastructure and decreasing the cost of access will empower smaller firms to take full advantage of the digital trade revolution (OECD 2017b). In this regard, it will also be critical for policy-makers to explore ways to meet key public policy objectives in a way that is least trade distorting and preserves the benefits of a free and open internet. This means engaging in greater international dialogue, involving different stakeholders, including firms of all sizes and civil society.

References

• Abe, M. (2013), Expansion of global value chains in Asian developing countries: automotive case study in the Mekong sub-region, In: Elms, D.K. and Low, P. (Eds.), Global value chains in a changing world, Geneva: WTO Publications, 385-409.

• Bernard, A., Jensen, J., Redding, S.J. and Schott, P.K. (2007), Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3), 105-130.

• BIAC, B20 China, World SME Forum, SME Finance Forum. (2016), Financing Growth; SMEs in Global Value Chains.

• Brynjolfsson, E. and Hitt, L.M. (2000), Beyond Computation: Information Technology, Organizational Transformation and Business Performance. Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (4), 23–48.

• Caliendo, L. and Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2012), The Impact of Trade on Organization and Productivity. Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(3), 1393-1467.

• Choquette, E. and Meinen, P. (2015), Export Spillovers: Opening the Black Box. World Economy 38(12), 1912-1946.

• Criscuolo, C. and Timmis, J. (2018), GVCs and Centrality: Mapping Key Hubs, Spokes and the Periphery. OECD Productivity Working Papers No. 12.

• Cruz, M. (2014), Do Export Promotion Agencies Promote New Exporters? Policy Research Working Paper No. 7004.

• European Commission. (2010), Internationalisation of European SMEs. Brussels: European Commission.

• G20/OECD. (2015), G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing.

• Gereffi, G. (2018), Global Value Chains and Development: Redefining the Contours of 21st Century Capitalism. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

• Iino, T., Inoue, H., Saito, Y. and Todo, Y. (2018), How Does the Global Network of Research Collaboration Affect the Quality of Innovation? RIETI Discussion Paper Series 18-E-070.

• Jin, H. and Hurd, F. (2018), Exploring the Impact of Digital Platforms on SME Internationalization: New Zealand SMEs Use of the Alibaba Platform for Chinese Market Entry. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 19(2), 72-95.

• Jinjarak, Y., Jose Mutuc, P. and Wignaraja, G. (2014), Does Finance Really Matter for the Participation of SMEs in International Trade? Evidence from 8,080 East Asian Firms. ADBI Working Paper Series No. 470.

• Kim, K.H. (2017), Korea seeks to boost SME exports. Korea Herald, January 30. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170130000253 (March 13, 2019).

• Lileeva, A. and Trefler, D. (2010), Improved Access to Foreign Markets Raises PlantLevel Productivity…for Some Plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(3), 1051– 1099.

• Melitz, M.J. (2003), The Impact of trade on aggregate industry productivity and intra-industry reallocations. Econometrica 71, 1695-1725.

• Nicita, A. and Gourdon, J. (2013), A Preliminary Analysis on Newly Collected Data on Non-Tariff Measures. UNCTAD Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities Study Series No. 53.

• OECD. (2008), Enhancing the Role of SMEs in Global Value Chains. Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD. (2013), Interconnected Economies: Benefiting from Global Value Chains. Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD. (2015), Implementation of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement: The Potential Impact on Trade Costs. OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate.

• OECD. (2016), OECD Trade by Enterprise Characteristic database. Retrieved from http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DatasetCode=TEC1_REV4 (March 13, 2019).

• OECD. (2017a), Services Trade Policies and the Global Economy. Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD. (2017b), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD. (2018), Fostering greater SME participation in a globally integrated economy. Discussion Paper for Plenary Session 3, the OECD 2018 SME Ministerial Conference, 22-23 February 2018, Mexico City, Mexico.

• OECD. (forthcoming), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook. Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD-INADEM. (2018), Workshop on Building Business Linkages that Boost SME Productivity. Workshop organised by the OECD in collaboration with the Mexican National Institute of the Entrepreneurs (INADEM), 20-21 February 2018, Mexico City, Mexico.

• OECD/The World Bank. (2015), Inclusive Global Value Chains: Policy options in trade and complementary areas for GVC Integration by small and medium sized enterprises and low income developing countries. Joint report prepared for submission to G20 Trade Ministers Meeting, 6 October 2015, Istanbul, Turkey

• Solano Acosta, A., Herrero Crespo, Á. and Collado Agudo, J. (2018), Effect of market orientation, network capability and entrepreneurial orientation on international performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). International Business Review 27(6), 1128-1140.

• Wagner, J. (2012), International Trade and Firm Performance: A Survey of Empirical Studies since 2006. Review of World Economics 148(2), 235-267.

• WTO. (2016a), Levelling the trading field for SMEs: World Trade Report 2016. Geneva: WTO Publishing.

• WTO. (2016b), Trade Finance and SMEs: Bridging the Gaps in Provision. Geneva: WTO Publishing.