This Policy Brief is offered to the Saudi T20 process, as a recommendation to the G20 in 2020.

Digital financial literacy (DFL) is becoming an increasingly important aspect of education for the Digital Age. The development of financial technology (fintech) products and services creates greater opportunities for financial inclusion but requires greater knowledge on the part of consumers to understand their costs and benefits and to know how to avoid fraud and costly mistakes. The key challenge is that there are significant gaps in DFL between men and women, between urban and rural residents and between small and large firms, among others. Digital financial literacy education strategies need to be targeted to disadvantaged groups to narrow these gaps.

Challenge

Digital financial literacy (DFL) is likely to become an increasingly important aspect of education for the Digital Age. DFL overlaps with financial literacy and digital literacy but has its separate aspects as well. In particular, the development of financial technology (fintech) products and services creates greater opportunities for financial inclusion, but at the same time requires greater knowledge on the part of consumers to understand the costs and benefits of the various products and to know how to avoid fraud and costly mistakes. These developments point to the need to develop country-level digital financial education strategies to improve digital financial literacy, with a focus on skills likely to be critical for those participating in the Digital Economy.

The key challenge is that the literature has shown significant gaps in financial inclusion and financial literacy between men and women, between urban and rural residents and between small and large firms, among others. While digital finance has been expected to help reduce such gaps, in fact digital finance early adopters tend to be those with higher education, higher income and higher levels of digital financial literacy. This suggests that digital financial literacy education strategies need to target disadvantaged groups of individuals and firms in order to narrow these gaps and enable fintech contribute to more inclusive financial and economic development, rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach.

Proposal

Background

G20 leaders have already endorsed the High-Level Principles on National Strategies for Financial Education in 2012 (G20 2012). However, these principles have been limited to traditional financial education which focuses on the understanding of basic principles of finance such as understanding of compound interest, inflation and asset diversification. We recommend that these principles be augmented by additional guidelines specifically focusing on ways to promote DFL.

In particular, G20 leaders need to enunciate principles for developing targeted approaches to raising DFL of specific groups, such as gender, urban/rural and small/large firms, rather than a uniform approach. One promising avenue is to enlarge the group of private stakeholders in national financial education strategies to include fintech and bigtech companies. Fintech companies and bigtech companies should be required to provide a certain level of financial and digital knowledge education to their customers by using their platforms and technology. With the wide networks established through their platforms, fintech and bigtech companies can easily extend financial knowledge to large numbers of people with different ages, backgrounds, locations, and level of education. Given that bigtech and fintech companies know their customers’ experiences very well, they should be able to design attractive mobile apps that can help users to gain financial literacy in an easy, interesting and interactive way. This could be an important way to leverage financial technology to promote digital financial literacy.

Definition of Digital Financial Literacy

While some previous literature (e.g., OECD 2017) has described various aspects of digital financial literacy, there is still no standardized definition of it. OECD (2018) discusses the importance of DFL, but does not provide a definition, which indicates a lack of consensus at the level of international coordination. Morgan, Huang and Trinh (2019) propose that DFL includes knowledge in four main areas: (i) fintech products and services, their benefits and drawbacks; (ii) new kinds of risks associated with fintech products and services; (iii) ways to protect oneself from these risks; and (iv) methods of redress if losses or other damage from such risks arise. These products and services generally fall into four major categories:

- Payments: Electronic money, mobile phone wallets, crypto assets, remittance services;

- Asset management: Internet banking, online brokers, robo advisors, crypto asset trading, personal financial management, mobile trading;

- Alternative finance: Crowdfunding, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, online balance sheet lending, invoice and supply chain finance, etc.; and

- Others: Internet-based insurance services, etc.

Increasing Importance of Digital Financial Literacy

Digital financial literacy has become increasingly recognized as an important requirement for effective digital financial inclusion, along with consumer protection, and has gained an important position in the policy agenda of many countries. In 2016 G20 leaders focused on digital financial literacy and endorsed the High-level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion, which include Principle 6 on “Strengthen Digital and Financial Literacy and Awareness” (GPFI 2016). However, most national financial education strategies do not address digital financial literacy specifically, but instead focus on basic financial concepts. Moreover, the G20 has not yet developed guidelines for digital financial literacy or digital financial education. Also, digital technology can make financial services borderless, which would allow people to easily access financial products and services in other countries. This shows the importance of global coordination not only in regulating fintech, but also in improving the digital financial literacy of the public.

Evidence of Gaps in Digital Financial Literacy

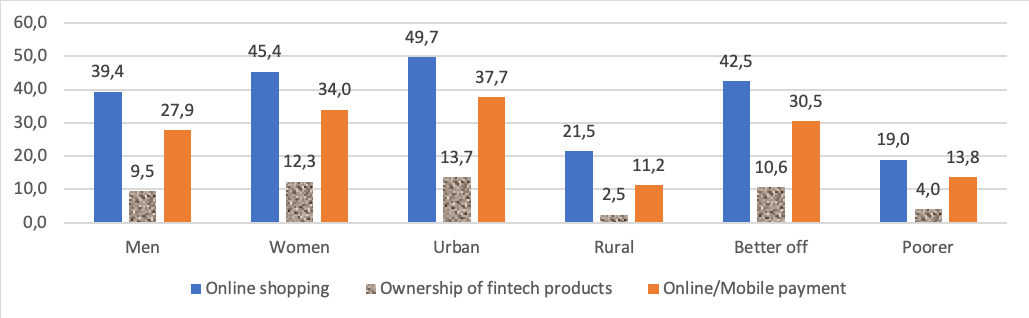

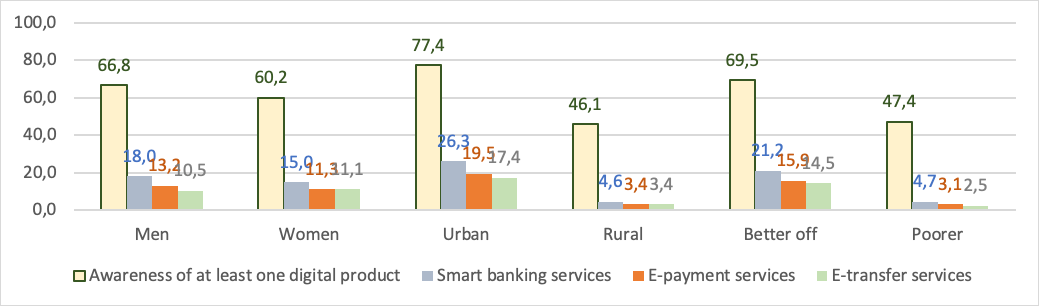

There is substantial evidence of gaps in DFL, especially among disadvantaged groups. Figure 1 shows the gaps in usage of fintech products by gender, location (urban vs. rural) and income group in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Viet Nam. In both the PRC and Viet Nam, gender gaps seem small, although many countries exhibit large gender gaps. In the PRC, the proportion of women adopting fintech products is actually higher than that of men. However, the gaps in fintech adoption among rural and urban residents and among income groups in both PRC and Viet Nam are substantial. For example, only 2% of PRC rural residents own fintech products while the figure for urban residents is 14%. The share of the poor (defined as those who live under the PRC’s poverty line [1] who hold fintech products is only about one third of the share of those with higher incomes. The same pattern is also observed in Viet Nam.

Figure 1: Gaps in usage and awareness of fintech products in the PRC and Viet Nam (% of total respondents)

PRC

Viet Nam

Notes: The poorer group in the PRC is defined as those who live under the Chinese poverty line. Viet Nam’s poorer group consists of those who lives in households with total income less than 85million VND (equal to 75% of the median household income in our sample).

Source: Authors’ calculations using ADBI’s Fintech Survey 2019 in the PRC and Viet Nam

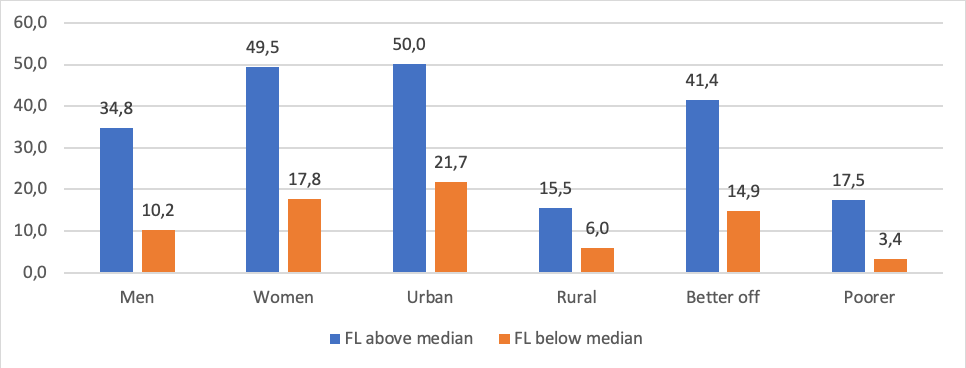

Fintech adoption has the potential vehicle to reduce gaps in financial inclusion, but it needs to be realized through higher financial literacy. For example, Figure 2 shows that those with higher financial literacy are more likely to use digital payments, even among disadvantaged groups such as rural residents and the poor. Since generally accepted measures of digital financial literacy are not yet available [2]. While Morgan, Huang and Trinh (2019) have proposed dimensions of digital financial literacy, developing such measurement is still in the nascent stage, we argue that gaps in financial literacy and digital literacy are likely to be correlated with gaps in DFL, since they are overlapping areas. Several studies have shown that gaps in financial literacy are rather high. For example, a recent survey showed that only 45% of Vietnamese rural residents are considered to have adequate financial literacy while the figure for urban residents is 61.1% (Morgan and Trinh, forthcoming). Similarly, only 44% of poorer individuals in Viet Nam have financial literacy scores above the national median score, while the figure for better-off individuals is 58%. The gaps in digital literacy also seem large between younger and older generations, between poorer and better-off groups and between urban and rural residents. The gap is partly attributed to the limited exposure to digital technology among the disadvantage groups. For example, in 2019, only 26.7% and 52% of Chinese rural residents have access to internet and own smartphones, respectively, while the corresponding figures for urban residents are 62% and 77.2% (Huang 2019)

Figure 2: Gaps in using online payment by level of financial literacy in the PRC and Viet Nam (% of total respondents)

PRC

Viet Nam

Notes: FL stands for financial literacy. The poorer group in the PRC includes those who live under the Chinese poverty line. Viet Nam’s poorer group consists of those who lives in household with total income less than 85million Vietnamese Dong (equal to 75% of median household income in the sample).

Source: Authors’ calculations using ADBI’s 2019 Fintech Survey in the PRC and Viet Nam

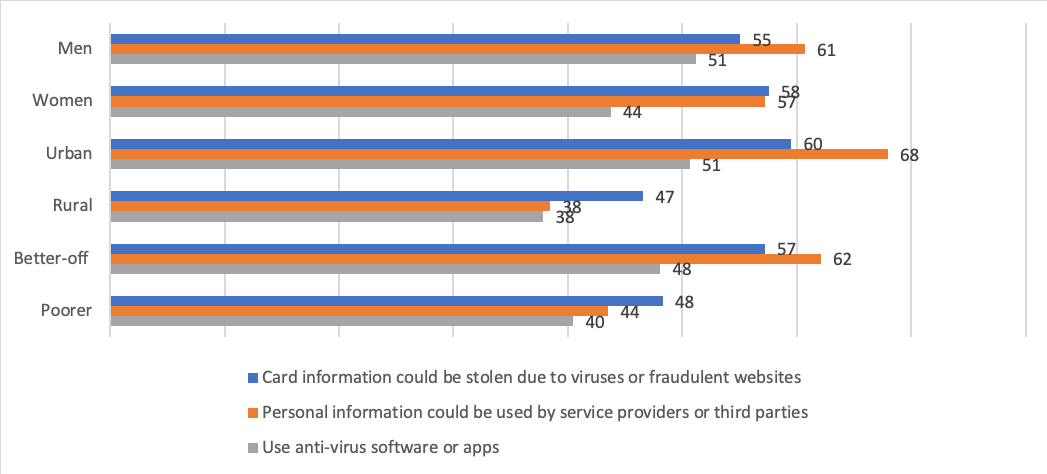

A recent survey conducted in Viet Nam in 2019 included several questions relating to digital financial literacy (Figure 3), and also showed significant gaps. Only 46% of eligible rural residents [3] aware that credit card information could be stolen because of virus and fraud website or apps while the figure for urban residents is 60%. Similarly, there is also 10 percentage points gap between poorer individuals and better-off individuals. Only 38% of rural residents vs. 68% of urban residents recognize that their digital information could be used by the service providers or by other parties. Only 51% of urban respondents and only 38% of rural respondents use any software or mobile apps to protect their computers and mobile phones. This evidence suggests that digital financial literacy is rather low in developing countries and that the gaps in digital financial literacy are large.

Figure 3: Gaps in some digital financial literacy indicators (% of eligible respondents)

Notes: Eligible respondents are those who use at least one fintech service, which accounts for about 45% of the total sample. The poorer group consists of those who lives in households with total income less than 85million VND (equal to 75% of median household income in our sample).

Source: Authors’ calculations using ADBI’s Fintech Survey in Viet Nam

Examples of Platforms and Related Firms Carrying out Digital Financial Literacy Programs

People’s Republic of China: With the rapid growth of the PRC’s fintech industry, hundreds of millions of financially underserved people and micro- and small- businesses now have access to a range of new digital financial products and services. However, advancing financial inclusion in rural areas is very difficult because a large proportion of rural residents have a very low level of financial knowledge.

The pilot financial education program implemented in Inner Mongolia by the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA), an NGO, and China Doorstep Finance (CD Finance), a microloan provider in rural area, with support from Visa, is an example of a promising approach that combines the provision of financial knowledge with the use of financial services. This case indicates that collaboration among the government, NGOs, fintech companies and rural financial institutions can achieve win-win solution. In 2016, the three organizations jointly initiated a three-year financial education pilot program in 10 poverty-stricken banners/counties in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region to advance financial inclusion and support poverty alleviation efforts through education and capacity building. CD Finance developed a series of financial education courses for loan officers and organized in-person financial education activities for farmers. Subjects included insurance, credit, financial management and fraud prevention. After training, CD Finance’s loan officers, most of whom were also farmers, became instructors. They visited the rural residents and taught them the financial knowledge and how to use financial services through their mobile phones. With the pilot program’s progress, loan officers at CD Finance not only helped others but also expanded their businesses and skillsets.

With better knowledge of loan repayment conditions, farmers not only abide by their credit agreements with CD Finance, but also pay more attention to their credit standings in their cooperation with banks, rural credit cooperatives, and other financial institutions. Following the publicity and explanation of digital finance tools, such as mobile banking transfers, increasingly more farmers are beginning to use these new technologies. This has greatly improved loan officers’ efficiency and connected them more closely with customers. CD Finance’s online-to-offline service model enables ordinary farmers to access the most advanced digital technology services, largely eliminating the digital divide. As of the end of 2018, a total of 209 financial education sessions had been held with 10,740 participants, of whom 63% were women and 95% were farmers. The program has benefitted more than 10,000 families and 44,000 farmers.

India: In 2016-2018, Sahyog Foundation, an Indian NGO specializing in empowering the powerless and educating the uneducated, collaborated with Indian fintech companies such as Oxigen World to carry out financial awareness campaigns in 22 rural areas in nine Indian states, where the share of the unbanked population is high. Reaching the most isolated villages was one of the major targets of its campaigns. In these campaigns, Sahyog Foundation and its sponsor companies made the villagers and semi-urban population understand that digital literacy is the ability of individuals and communities to understand and use digital technologies for meaningful actions in life situations. The participants also experienced various transactions through fintech apps. The awareness program covers best practices, tips, and tricks to be followed while conducting transactions through the digital channels. To promote digital banking, Sahyog Foundation associated with villagers, slum dwellers, schools and colleges to create awareness and educate various stakeholders such as employees, students, teachers, and traders on the benefits of going cashless to promote the use of digital banking channels for financial transactions. They also reached out to school students. To get target audiences involved, they made the activities very interactive, educative and entertaining by using street theater, drum beating, banking benefits and saving games, group gathering and announcements (Sahyog Foundation 2019).

Policy Recommendations

Extending DFL to disadvantaged groups is critical to achieve equitable financial inclusion in the Digital Age. Including various stakeholders such as fintech and bigtech companies, NGOs and financial institutions in national financial education strategies and seeking innovative means of collaboration for delivering digital financial education are promising avenues.

- The G20 member countries should establish guidelines for the inclusion of fintech and bigtech companies in national financial education strategies and promote recommendations that fintech and bigtech firms be required to provide a certain level of digital financial education to their customers, especially disadvantaged groups. With their wide networks and detailed user databases, fintech and bigtech companies can easily extend financial knowledge training to large numbers of people in targeted ways.

- However, online training along may not be sufficient. Given that disadvantaged groups are usually under-educated people, in-person training implemented by NGOs and financial institutions in their neighbourhood will also be needed to increase the effectiveness of such programs. The combination of online and offline education model has great potential to eliminate these digital gaps. Therefore, G20 member countries should also develop guidelines for such coordinated online and offline models to be included in national financial education strategies.

Footnotes:

[1] The PRC’s poverty line was RMB3,747 per year in 2019.

[2] While Morgan, Huang and Trinh (2019) have proposed dimensions of digital financial literacy, developing such measurement is still in the nascent stage.

[3] Eligible respondents are those who use at least one fintech service. All figures in this paragraph are for eligible respondents.

References

Huang, B. Forthcoming. Fintech and Financial Literacy in PRC. ADBI Working Paper Series.

Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI). 2016. G20 High-Level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion. Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion. Available at: https://www.gpfi.org/publications/g20-high-level-principles-digital-financial-inclusion

Group of Twenty. G20. 2012. G20 Leaders Declaration. Los Cabos, Mexico, June 19. Available at: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2012/2012-0619-loscabos.html

Morgan, P.J., B. Huang, L. Trinh. 2019. The Need to Promote Digital Financial Literacy for the Digital Age. T20 Policy Brief. Available at: https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-need-promote-digital-financial-literacy/

Morgan, P.J., L. Trinh. Forthcoming. Fintech and Financial Literacy in Viet Nam. ADBI Working Paper Series.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2017. G20/OECD INFE Report on ensuring financial education and consumer protection for all in the digital age. Paris: OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/finance/g20-oecd-report-on-ensuring-financial-education-and-consumer-protection-for-all-in-the-digital-age.htm

OECD. 2018. G20/OECD INFE Policy Guidance on Digitalisation and Financial Literacy. OECD: Paris. Available at: https://www.gpfi.org/publications/g20oecd-infe-policy-guidance-digitalisation-and-financial-literacy

Sahyog Foundation. 2019. Financial Digital Literacy and Awareness Programs (Including Nukkad Natak). Available at: http://www.sahyogfoundation.in/financial-digital