The authors call upon G20 leaders to recognize cities as active agents in managing migration, in recognition of the fact that migrants tend to settle in urban areas, when they arrive in their destination country. G20 countries need to strengthen institutional capacity at the city level, empowering cities to determine the legal status and protect the rights of all migrants (voluntary and involuntary). We urge G20 countries to focus on the key challenges cities are presented with, as a result of migration, particularly the provision of affordable housing, education and skills development, access to health services (including mental health services), access to transportation modes, additional stress on the natural environment and increased consumption and waste. We encourage G20 countries to make evidence based decisions rather than based on public opinion, perception and sentiments. To ensure inclusivity and integration, G20 countries should work with city leaders to engage migrants in their urban planning processes. We ask the G20 countries to consult with the private sector not only as potential migrant employers, but also as a catalyst of economic and social change by lending voices on formulating migration policies, contributing to multi-stakeholder partnerships involving all actors and as solutions providers.

Challenge

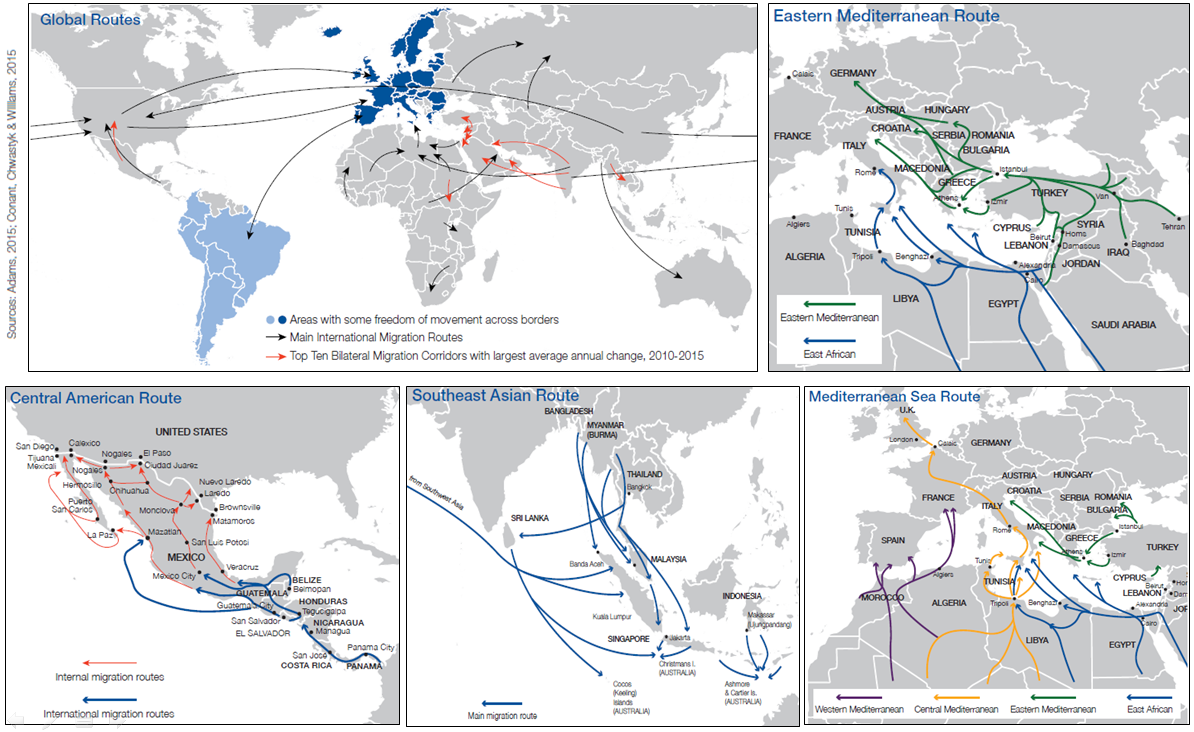

In 2015, mass migration affected nations across the world with routes cutting paths through Central America and Mexico, Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean Sea. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 – Some of the world’s many migration routes

Today, there are more than one billion migrants in the world, representing one seventh of the world’s population. This level of human mobility is unprecedented and continues to rise at a rapid rate. According to United Nations, this one billion is comprised of an estimated 258 million international migrants (19% of whom arrive in the US, followed by 14% in Saudi Arabia, Germany and Russia) (UN DESA, 2017) and 763 million internal migrants (UN DESA, 2013). Migration has been an ongoing trend for centuries with growth in annual international migration at twice the rate of annual natural population growth in the world.

Migrants continue to be drawn to cities in search of a better quality of life, greater job prospects and ease of access to urban infrastructure and services

Cities address the immediate needs of migrants and respond to some of the challenges related to their integration into society. The presence of migrant communities in cities also accelerates their chances of integration and draws further migrants towards cities. In addition, the projected increases in urbanization and migration indicate that cities will continue to play an integral role in human mobility in the coming decades.

And yet statistics on the number of migrants in cities are limited, particularly those pertaining to developing economies, where such information could inform urban planning processes and ensure that cities are better prepared to manage migration.

Approximately one in five international migrants are estimated to live in just 20 cities – Beijing, Berlin, Brussels, Buenos Aires, Chicago, Hong Kong SAR, London, Los Angeles, Madrid, Moscow, New York, Paris, Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Vienna and Washington DC.

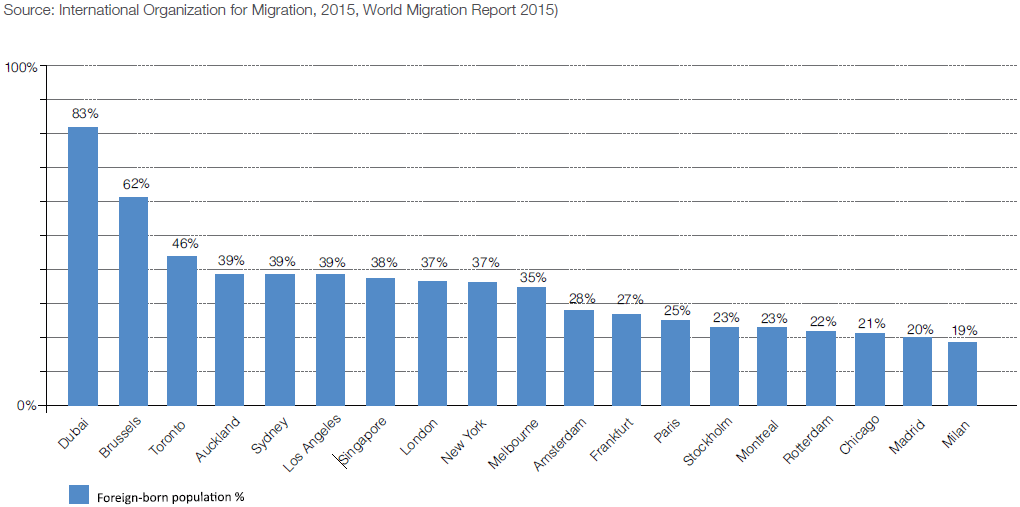

According to The International Organization for Migration, Dubai has an appropriate foreign born population of close to 83%, while in Brussels its 62%, in Rotterdam close to 49%, in Toronto 46%, Los Angeles 39%, New York 37%, Melbourne 35%, Montreal 33%, Amsterdam 28% and Berlin 18%. (Figure 2)

Figure 2 – Foreign Born Population in Major Cities (as % of Total)

The emerging drafts of Global Compacts on Migration and Refugees are emphasizing the role of cities as stakeholders and are encouraging them to form partnerships with other cities, to share best practices while also working towards policy coherence, at different levels of government, to address migration related challenges.

In 2017, the World Economic Forum collaborated with PwC, in order to understand the key challenges faced by cities that are most affected by migration. A collection of 22 case studies from some of the most affected cities across the world revealed challenges in the following areas:

- Housing – One of the biggest challenges cities face is providing adequate and affordable housing to migrants, which is often in limited supply even for the city’s existing residents. Internal migrants arriving from poorer parts of the country into cities are often unable to afford housing, which leads them to live in slums or squat. An estimated 881 million urban residents live in slums, the number having increased 28% worldwide over the past 24 years. Although the proportion of urban populations residing in slums has fallen over the past two decades, the number of slum dwellers continues to increase. The situation is equally grave for economic migrants who are unable to own homes either due to long housing waiting times (which can run into years) or because the exorbitant home prices have made homes unaffordable even for the middle income groups.

- Education and Language Skills – Soaring immigration directly affects the availability of places in primary schools, and inevitably pushes schools towards increasing class sizes and adding classrooms. A lack of such resources poses big issues for governments, undermining efforts to keep class sizes down and to provide school places for all children. The situation is further complicated when the medium of instruction is not in the native language of the immigrant. Language skills typically become an obstacle to entering vocational training. Cities often also do not have the competence for tertiary education or to recognize prior learning.

- Access to physical and mental healthcare – The presence of infectious diseases in migrants causes concern for cities, which in some cases have opted to screen for them, leading to debates on the human rights of migrants. Migrants with pre-existing health conditions can strain cities’ healthcare systems. In cities with a significant migrant population living in slums, migrants’ living conditions and other social determinants exacerbate the physical, mental and social health risks as well.

- Access to the city – Migrants depend on transportation to commute, creating increased demand for such facilities. Upon arriving in a new city, one of migrants’ primary concerns is how to avail of public transportation services.

- Stress on natural resources – The influx of migrants places increaed demand on water resources, followed by an associated increase in sewage generation which, in turn, creates demand for waste water treatment facilities. A lack of such facilities results in an increased risk of untreated waste contaminating water, rendering more sources of water unusable and depriving more people of an increasingly scarce resource.

- More waste generation – Migration can greatly exacerbate the challenges of managing sewage and waste in a city given the growth of the population, but the city cannot always meet the demand due to insufficient capacity. The influx of refugees catalysed better waste infrastructure for residents in Amman, where a comprehensive program is been developed to reform the solid waste sector that will lead to the generation of renewable energy, reduction of CO2 emissions, and creation of new jobs. In developing nations, poor migrants living in slums or informal settlements face increased risks from spreading communicable diseases especially when waste is dumped in open streets that are usually not accessible by waste collection trucks.

- Increased Energy Consumption – A study in Hanoi, Vietnam on CO2 emissions revealed that rural-to-urban migration is shown to have a significant and negative influence on residential energy consumption and CO2 emissions, while there was no significant effect on urban-to-urban migration. Cities are underestimating the impact of rural-to-urban migration, such that energy consumption estimates are lower when the population has increased due to this migration, than through urban-to-urban migration and natural population growth. These outcomes have imperative implications for the energy policy of developing-country cities in the context of population growth and energy utilization.

- Integrating Migrants – Migration involves complexities associated with diversity of race, religion, ethnicity, language and culture. It can lead to social tension associated with xenophobia and discrimination and to violence in neighbourhoods, workplaces or schools. Several cities in Europe have struggled to integrate their populations, and many African cities experience xenophobic and violent behaviour arising from differences between people’s tribes or clans. With migration policies mainly defined at the national level, cities are typically expected to develop their own strategy and policies to integrate people into the community. Emerging differences between the interests of migrants, city governments, and countries excessively controlling the movement of migrants has led to a misaligned outlook on immigration in such countries. In the United States, some sanctuary cities support legislation that relieves their police force from cooperating with certain federal immigration controls that are regarded as prejudicial to migrant communities.

Proposal

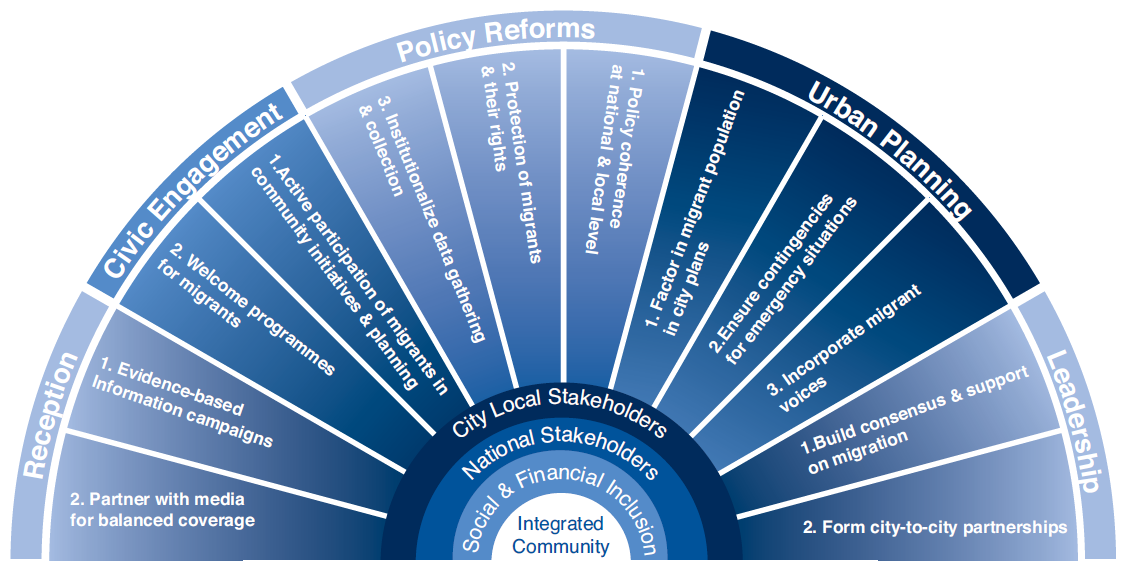

Cities in G20 countries need to accept more responsibility for managing migration and its impact. City leaders, private sector, civil society and migrants themselves would have a role to play in helping the city prepare for future immigrant flows. A migration preparedness framework was conceptualized in a report by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with PwC (Figure 3).

Source – Migration and Its Impact on Cities, 2017

Figure 3 – Framework for Migration Preparedness

The report further analyzed the impact of migrantion on 22 of the most affected cities in the world and identified key opportunities for each of the challenges aforementioned.

- Housing – Cities in G20 countries need to explore opportunities to repurpose vacant spaces or underutilized buildings for migrants. Innovations in alternate construction methods (3D printing, modular construction, etc.) and materials (recycled bricks, etc.) and microfinancing solutions can help make short term housing a reality for immigrants.[i]

- Education and Language Barriers – The private sector in G20 countries can help create a platform for educating and upskilling migrants in collaboration with city governments.Countries should facilitate partnerships with city administrations and the private sector encouraging the idea of employing migrants is in their long term self interest. G20 countries could carry out a needs assessment of skills that are in shortage and then develop training programs tailer fit to meeting these needs with immigrants.[ii]

- Access of physical and mental healthcare – G20 countries must ensure that cities are able to consult the private sector in developing insurance products and other migrant sensitive services that cover migrants for basic health care services. Similarly, access to mental healthcare services is particularly important for involuntary migrants who have been compelled to leave their homes and may need access to mental healthcare services.[iii]

- Access to the city – G20 countries need to ensure that migrants are able to secure easy and equal access to the public transit systems, as the city residents, by granting special or temporary access until their legal status is determined. Alternatively, a program that uses discarded vehicles can also help migrants navigate through the city.[iv]

- Keeping the neighbourhoods clean – G20 countries need to work with city governments in ensuring water and sanitation facilities are provisioned in areas that are deprived from access to formal urban services, especially in informal settlements where most poor migrants reside. Additionally, awareness campaigns on the benefits of safe disposal and maintaining high levels of hygiene can significantly help reduce chances of disease and illhealth.

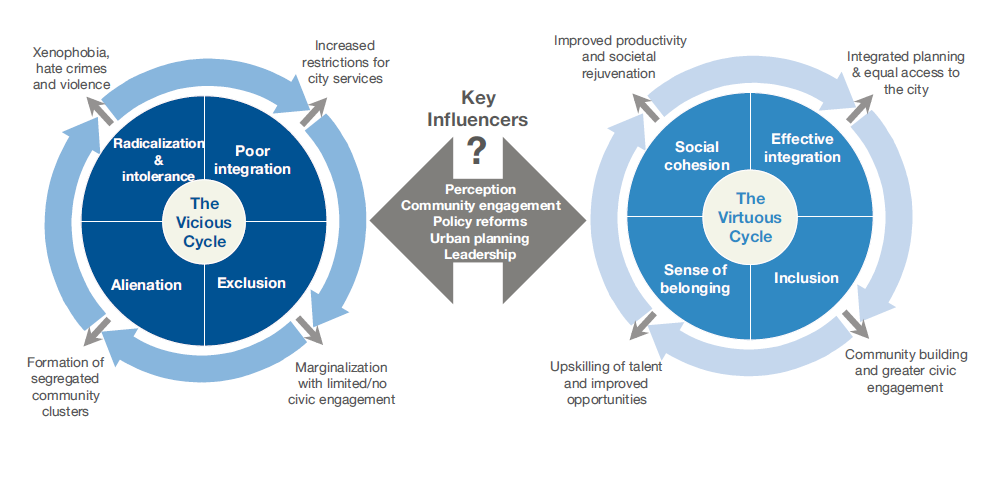

- Integrating migrants – Governments in G20 countries need to embrace the virtuous path of integrated urban planning recognizing the needs of migrants and natives collectively. Inclusive cities are able to solicit active engagement from all communities, and over time can create a greater sense of belonging among migrants, who will see potential benefits in investing their time, efforts and resources into improving their skills, and are therefore able to tap into better opportunities, which will improve their overall quality of life (Figure 4)

Source – Migration and Its Impact on Cities, 2017

Figure 4 – Migrant’s path at the destination – Vicious or Virtuous?

Further, governments in G20 countries need to ensure that there is policy coherence at different levels. Rather than impose sanctions on sanctuary cities, the government should consider the potential benefits in undocumented migrants being encouraged to report crime, seek healthcare and enrol in schools, all of which they would have avoided otherwise, for fear of deportation.

[i] In Austin, USA Technology startups like ICON and New Story have developed a 650 square feet home prototype that can be built in less than 24 hours, costing less than $10,000. In developing countries, the cost could go as low as $4,000 each. Similar technologies are being adopted in in Moscow, Dubai, Amsterdam, and other cities as well.

[ii] The Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council (TRIEC) facilitates active partnerships with the city administration to employ immigrants. Similarly, The Hague Process in Netherlands examines present and future structural labor shortages and skills gaps in cities and then develops tailored training programs to meet these needs and upskill the migrant talent pool.

[iii] Applications like X2AI – a Silicon Valley startup – have created an artificially intelligent chatbot called Karim that can have personalised text message conversations in Arabic to help people with their emotional problems.

[iv] The Bike Project in London acquires abandoned or discarded bikes, restores them to roadworthy condition and donates them to refugees.

References

- Migration and Its Impact on Cities, World Economic Forum in collaboration with PwC, October 2017. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/migration-and-its-impact-on-cities

- Adams, P., 2015. BBC News, “Migration: Are more people on the move than ever before?” Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-32912867

- Conant, E., Chwastyk, M. and Williams, R., 2015. National Geographic, “The World’s Congested Human Migration Routes in 5 Maps”. Available at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/09/150919-data-points-refugees-migrants-maps-human-migrations-syria-world/

- International Organization for Migration, 2015. World Migration Report 2015: Migrants and Cities: New Partnerships to Manage Mobility. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/wmr2015_en.pdf

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), 2013. Cross-national comparisons of internal migration: An update on global patterns and trends. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/technical/TP2013-1.pdf.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), 2017. International Migration Report 2017. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, September. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf