This article is a pre-publication from the next issue of the Global Solutions Journal, which will be published in January 2021 on the occasion of the beginning of the Italian G20 Presidency

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for a new form of digital governance to support consumers around the world. Digital consumer policy has to be fit for a more digitalized and sustainable world and tackle inequality in the post-COVID world.

Governments around the world have been showing strong and decisive action to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides numerous measures to safeguard public health, policymakers have focused on supporting firms to prevent large-scale insolvencies. Central Banks’ monetary policies as well as special spending programs add to macroeconomic stability in the crisis and cushion the freefall of the global economy.

Yet, besides firms and production, COVID-19 has brought massive disruption to everyday life and hit one group particularly hard: consumers. Many are suffering from straitened budgets – stemming from unemployment or short-time work schemes – and are struggling to meet credit charges or to pay rents. Many countries have taken measures to mitigate the consequences of the pandemic for consumers, such as reductions in value-added tax or prosecution of consumer infractions – like unfair competition, for instance.

But while such measures are helpful, the rise in global inequality will be significant – and persistent – for several reasons. In terms of persistence, the duration of the crisis is evident: case numbers have been climbing due to a “second wave” in many countries at the end of 2020. In terms of rising inequality, one thing is clear: unlike most of Western Europe and other highly developed economies, developing countries do not possess the fiscal space to boost the economy with expensive stimulus programs and shield consumers from job and income losses at large scale. Thus, between-country inequality will likely rise sharply due to the pandemic.

But also within-country inequality between consumers could increase quite significantly, one reason being the digital transformation. As a consequence of the crisis, many employers – private and public alike – are already or will be investing in their digital infrastructure. This development will probably come mostly to the benefit of highly educated, urban consumers, as several major cities have become hubs for digital business models. More vulnerable consumers, like those living in rural areas or in less-affluent cities will not be exposed to heavy investment in digital capabilities around them. And moreover, many of those vulnerable consumers may fear that their jobs could become obsolete with digitalization on the rise.

The rise of digital platforms and market power: A burden for consumers

Finally, there is a further remarkable development that is related to the pandemic-induced acceleration in the use of digital services: the ever more important role of digital platforms. Clearly, platforms can work well for many consumers given their potential for better transparency, lower prices and more convenience. Moreover, platforms can certainly play a useful part during the pandemic when physical shopping should be avoided. But the digital economy also requires stronger consumer and data protection – where platforms with already staggering market power have become even more dominant and successful with the coronavirus.

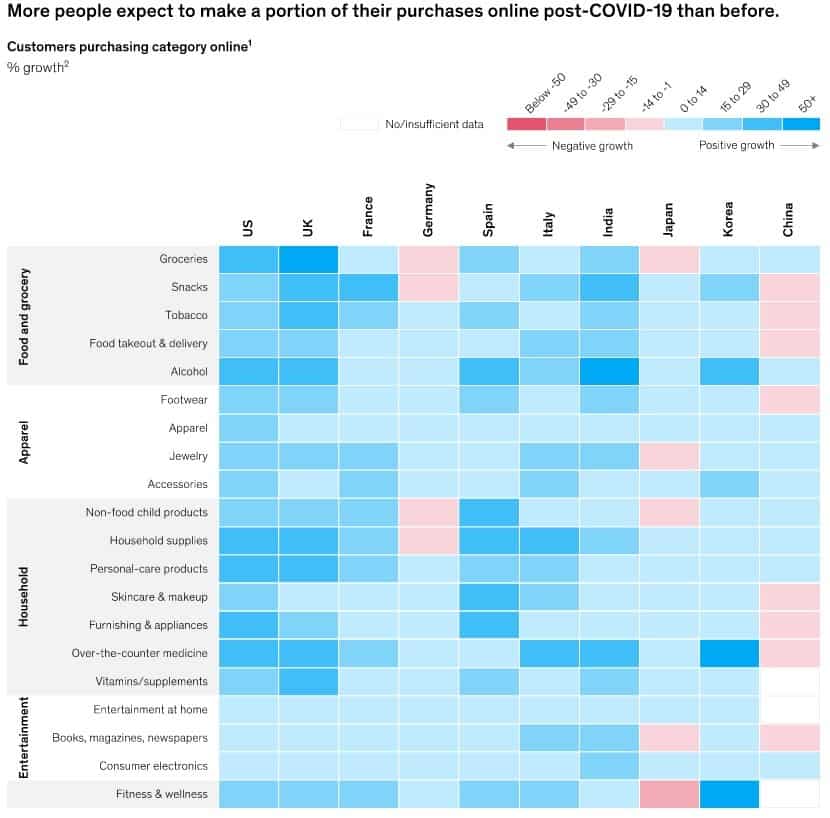

Indeed, Figure 1 suggests that most consumers around the world will shift consumption patterns to the online arena, which is likely to strengthen online platforms. Apart from digital data protection we also need to enhance transparency and the digital literacy of consumers, especially when it comes to the – often opaque – use of data in digital services. This observation comes at a time when digital platforms and tech firms have gained very significant market power, mainly through network effects. The surge in dominance of the firms commonly known as “GAFA” (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon) are prime examples of this development.

While there appears to be a strong focus on digital platforms in the public debate, we should also focus on the offline world. Value chains of firms in sectors such as logistics, food and health have become increasingly digitalized, which appears to have helped the already dominant firms in these sectors. Novel research finds that market concentration and market power across industries has increased in many sectors, as “super star firms” have taken a larger share of the economic pie in their respective markets.

It is clear that increasing market power of platform firms can prevent new, innovative firms from entering markets, and thus suppress competition and innovation. This is not just bad for consumer prices. When single firms become too dominant, they can set the sole standards for consumer protection when it comes to the increased use of digital data in business models.

It is becoming clear that both digitalization (partly accelerated by the pandemic) as well as lower incomes and job losses due to COVID-19 are putting severe pressure on consumers. In our view, first and foremost, more consumer confidence can pave the way out of the crisis. There are several important points to consider from a consumer confidence viewpoint.

Confidence is key

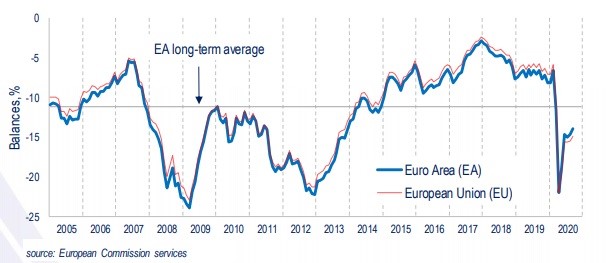

First, consumer confidence will be key to a swift recovery. Only with rising consumer trust will firms and the overall economy be able to recover promptly. The European Union’s single market (the world’s largest economic area) provides a good example. Figure 1 indicates that consumer confidence in the EU has not yet returned from its low point after the outbreak of the pandemic and remains well below its long-term average.

Second, consumers are a not a monolith. Some have been hit particularly hard: solo self-employed people, single-parents, artists, those living in the worst-affected countries or who themselves work in services such as tourism. So generous support for consumers will be important to keep already-rising inequality at bay.

Against this background, we should ask how a suitable consumer-oriented policy framework can combine digital governance and consumer protection to make consumers a top policy priority. One example of “good practice” could be the EU’s framework on consumer policy, commonly known as the Consumer Agenda.

Focal points: Recommendations by the EU Trio pPresidency can serve as an example

Recently, the trio presidency of the Council of the EU – the Netherlands, Slovakia and Malta – presented a joint paper, “Lessons Learned from the Covid-19 pandemic”. It highlights important areas in which consumer policy requires immediate action as an antidote tothe pandemic.

The recommendations pick up on the focal points of the Consumer Agenda process in the EU. They recommendations of the three countries include:

- Improvement of consumer protection within financial services. The review and improved rules of the Consumer Credit Directive (2008/48/EC) should be adjusted to the digital era while ensuring a high level of consumer protection. The review should also examine the risks of over-indebtedness in the time of crisis.

- Addressing consumer vulnerability. Many consumers in the European Union lost their jobs or faced a considerable reduction of their income. As a consequence, consumers are facing difficulties in complying with credit / financial obligations, and many find themselves in a vulnerable situation and are experiencing indebtedness. This problem needs to be addressed in order to share best practices and information, and to find a common solution for European consumers. Possible approaches could include promoting inclusion, empowering consumers regarding their rights through consumer-supporting awareness campaigns, and developing common tools that improve consumer experiences. Studies by the European Commission on consumer vulnerability should be taken into account in the process of designing these measures. We intend to support research on the differences in quality of life for consumers across European regions and the welfare effects of EU Regional Policy.

- Consumer protection on platforms. Due to the considerable increase in fraudulent, misleading and legally non-compliant offers in e-commerce and on online sales platforms and “fake shops,” such platforms should assume greater responsibility to tackle legally non-compliant offers. The Trio considers it therefore of central importance that the Digital Services Act announced by the Commission will introduce a higher level of responsibility in particular for large online platforms. In addition to these regulatory measures, an expansion of quality-based information and educational offers for consumers could be useful. Furthermore, administrative and regulatory measures to strengthen competition between platforms so that consumers also have freedom of choice should be considered. However, the responsibility of platforms and sellers should remain clearly distinguishable.

- Promoting sustainable consumption. Some consumers changed their lifestyle and consumption patterns in the face of the crisis – often with environmentally friendly effects. Beyond times of crisis, consumers should be encouraged to become actors in the green transition. This requires innovative solutions, an adequate legal framework promoting long product lifespans and reparability, appropriate information and consumer education. Sustainable consumption should not be dependent on income, but should be accessible for everyone.

- Travel and passenger rights. In the past, consumers have repeatedly endured painful experiences with corporate bankruptcies and inadequate bankruptcy protection. Thus, it should be examined whether and how insolvency protection could be improved in the area of transport, especially for air carriers.

- Review of the Directive on General Product Safety. The review of the Directive on General Product Safety (2001/95/EC) should be conducted with a view to the challenges brought by new technologies and online sales to ensure the safety of non-food consumer products, better enforcement and more efficient market surveillance.

The full list of areas identified by the Trio Presidency also includes joint research on vulnerable consumer groups and the monitoring of consumers’ rights during the COVID-19 crisis – both of which would also be of great value for other G20 countries.

Empowering consumers for a better digital governance

Overall, the Consumer Agenda of the European Commission is a good example of how policy frameworks should combine the benefits for consumers from digital business models and the high level of protection needed to empower consumers. Only this way will countries around the world manage to help consumers – and thus determine how well all of us can make it out of the crisis. In a broader sense, it will thus also determine G20 citizens’ sentiments post-pandemic – in particular, whether they feel that policymakers balance the interests of consumers and businesses.

Thus, it should be noted that consumer policy is also a matter of social cohesion and thus relevant to the state of civil society across the globe. On a wider horizon, the focus of consumer policy should be on empowering consumers – above all, giving them a say and adequate influence in shaping digital governance, which will in the end be conducive to liberal democracy and open societies. Such empowerment in the digital sphere will be ever more important as the world becomes much more focused on digitalization and a sustainable environment in the aftermath of COVID-19. With the right strategy, the “new normal” could be most beneficial to consumers – and the overall economy.

Bibliography

Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2017). Concentrating on the Fall of the Labor Share. American Economic Review, 107(5), 180-85.

De Loecker, J., Eeckhout, J., & Unger, G. (2020). The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 561-644.

Trio Presidency Paper (2020). Consumer protection in Europe – Lessons learned from the COVID-19-pandemic. Available at www.bmjv.de .

Christian Kastrop currently serves as State Secretary, German Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection

Dominic Ponattu is Private Secretary to the State Secretary, German Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection

The Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection is a cabinet-level ministry in Germany. The ministry creates and changes law in the classic core areas related to Constitutional law and also analyzes the legality and constitutionality of laws prepared by other ministries. Moreover, the Ministry is also responsible for the area of consumer policy and consumer protection in the digital sphere, the goals of which are to establish the conditions for safe and self-determined consumer activity.