Last year, under pressure from its own employees, Google announced that it would not renew a contract with the US Department of Defense on Project Maven – a project to use machine learning to improve surveillance and target identification by military drones. Google employees felt that the initiative was “in direct opposition to our core values” and that the company “should not be in the business of war.” Google executives eventually agreed not to renew the contract. Yet, while Google appears to have ended its direct participation, Project Maven itself is ongoing; other artificial intelligence (AI) researchers and firms are stepping in to do the work. What was deemed an unethical use of AI by Google employees appears not to present ethical red flags for others.

Although most agree that AI should be developed and deployed ethically, governments, industry and civil society organizations have struggled to agree on a shared set of ethical principles and how they apply. The non-profit organization Algorithm Watch has compiled an AI Ethics Guidelines Global Inventory of more than 80 different ethical frameworks and notes that the sheer number and length of the documents have made it impossible for them to identify anything but high-level trends and themes. Developing a common AI ethics framework is no small task.

Amid the cacophony of AI ethics initiatives, however, there is an emerging view that human rights frameworks could provide appropriate standards. Some organizations are recommending the use of human rights standards — enshrined in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) — to regulate the development and use of AI. And the idea is gaining traction. The United Kingdom has launched the Human Rights, Big Data and Technology Project to examine “the adequacy of existing ethical and regulatory approaches to big data and artificial intelligence from a human rights perspective.” Similarly, the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Project on Human Rights and Technology is exploring how AI can be harnessed to “advance human rights and make Australian society fairer and more inclusive” while recognizing and addressing the “threat that new technology could worsen inequality and disadvantage.”

A Human Rights Lens for AI Ethics?

A human rights approach to AI ethics has a number of advantages. By providing a shared ethical language, it can help to overcome the challenge of coordinating multiple, and sometimes incompatible, frameworks. Moreover, if properly implemented and enforced, a human rights approach could limit opportunities for firms to adopt self-serving codes that reinforce inequality and injustice. By intention and design, human rights put human dignity and welfare — not profit or political power — at the centre of moral concern. Finally, because human rights already enjoy widespread (although certainly not universal) legitimacy, gaining support for their use in the context of AI is a manageable feat.

Yet, if human rights standards are going to be a meaningful and effective part of AI ethics, advocates and policy makers will need to address at least three challenges.

Covenants Without the Sword

It is one thing to agree on a set of principles, but another for those principles to have real force in regulating behaviour. Advocates of human rights approaches will need to identify mechanisms and institutions that ensure respect for human rights and procedures and penalties for violations. As Thomas Hobbes noted in Leviathan, his 1651 essay on the social contract, “Covenants, without the Sword, are but mere Words, and of no strength to secure a man at all.”

There already exist a range of human rights monitoring and enforcement mechanisms that could be used to regulate state use of AI — although additional expertise and processes might be needed. However, a major challenge arises in the context of industry use of AI, given that human rights were intended, at least initially, to constrain the exercise of sovereign state power, not the behaviour of private business. How can standards intended for state actors be adopted and enforced among industry actors?

In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council endorsed a set of Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights for states and companies to “prevent, address and remedy human rights abuses committed in business operations.” And there are encouraging examples of industry monitoring and reporting — such as global efforts focused on labour standards in global supply chains — that provide lessons in the AI context. Still, there is much work to be done before human rights can serve as enforceable standards for firms developing and using AI. Even then, the history of human rights is arguably as much a history of violations without consequence for perpetrators as a history of wider application and stronger protection for vulnerable groups and individuals. It is not clear how human rights as ethical standards for AI will fare any better.

Interpretation

A second challenge concerns interpretation. Human rights provide a language for identifying and discussing a range of moral concerns, but, like all languages, there is room for different and sometimes conflicting interpretations — even among well-intentioned agents aiming at mutual understanding.

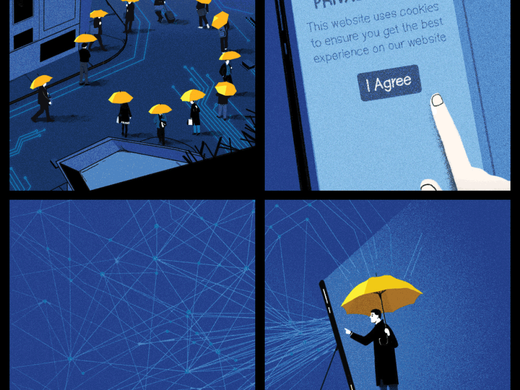

Article 12 of the UDHR, for example, holds that “no one shall be subject to arbitrary interference with his privacy.” But reasonable people can disagree about what “arbitrary,” “interference” and “privacy” mean. If an organization observes and collects data on individuals’ movements in public spaces, are they interfering with privacy? If firms or states somehow alert people that such data will be collected before they enter those public spaces — but don’t require explicit consent — is that an arbitrary or a non-arbitrary interference? That we can reasonably disagree about these questions highlights the interpretation challenge. A human rights approach will need to establish institutions and mechanisms that allow for broad, inclusive and meaningful deliberation about what rights mean and what is required to ensure their protection.

Moving beyond Minimal Standards

Finally, ethics requires more than human rights. Consider that while there are human rights that cover property and basic human needs, they are largely silent on questions of distributive justice, about how much inequality, if any, is permissible in a society.

As the philosopher Mathias Risse argues, “a society built around rights-based ideals misses out on too much. Over the last 70 years the human-rights-movement has often failed to emphasize that larger topic of which human rights must be part: distributive justice, domestic and global.” In short: AI can be used in ways that do not violate rights, but those uses might not fit with the kind of society that citizens want to create and sustain.

To the extent that AI systems can reinforce unequal distributions of power and wealth without violating specific human rights, a human rights approach to governing AI can be considered incomplete.

A Bridge Upon Which We Can Meet and Talk

Eleanor Roosevelt, the chair of the UN committee that drafted the UDHR, recognized that the Declaration was imperfect and incomplete. Nevertheless, as she once remarked about the United Nations itself, human rights constitute “a bridge upon which we can meet and talk.” Human rights provide a starting point and a shared language for respecting and protecting the dignity and well-being of human beings. Advocates for a human rights approach to AI ethics have identified a bridge — a shared language — upon which we can meet and talk. But, like Roosevelt, we must recognize that human rights provide only a starting point for the very difficult work of creating the conditions for a just and ethical world.