Changes in global value chains and reshoring trends brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic represent an opportunity for sustainable and inclusive economic development of the Mediterranean region. While the region has increased its participation in trade and global value chains, it remains below its potential due to limited connectivity and the lack of adequate investment in infrastructures. To boost competitiveness and attract near-shoring investments, an upgrade of the Mediterranean region’s logistic facilities as well as an integration of its supply chains is essential. Such goals would be best achieved through significant international cooperation, relying primarily on fora to set common standards for infrastructure investment, private sector co-operation and development banks to provide the financial resources for the deployment of infrastructure.

Challenge

Infrastructure can facilitate investment, promote industrial development and economic diversification of the economies in the MENA region. It can lower logistics costs, facilitate trade, enhance export diversification, and boost competitiveness. Yet, such potential outcomes can materialise with a high quality of infrastructure in the form of effective delivery of public goods and services, increased safety, and low environmental impact. The Covid-19 pandemic is also creating the need for technologically advanced, sustainable, and resilient infrastructure that can support the economic recovery.

Investments of at least USD 100 billion annually to 2030 (or 7% of GDP) are required to maintain existing and create new infrastructure in the MENA region (World Bank, 2020). This represents an opportunity to promote quality infrastructure investments that incorporate elements of economic efficiency, in addition to limiting the environmental and social costs. The 2019 G20 Principles for Promoting Quality Infrastructure Investments also reaffirm the critical importance for stakeholders to work coherently to bridge the existing global demand-supply gap of infrastructure investment for strong, sustainable, and balanced growth, and to enhance resilience in the societies.

There is no denying that the choices MENA economies make, and the approaches they take with respect to infrastructure delivery will have a long-term impact on the Euro-Mediterranean integration. Countries should identify good practices and develop guidelines on infrastructure quality, considering the principles and related issues agreed by international fora. As such, there is a need for a platform to facilitate a multi-stakeholder dialogue in the Mediterranean around the issue of promoting quality infrastructure investments and by sharing good practices from G20 and other relevant countries.

PRIVATE FINANCING IN THE MENA REGION IS LIMITED

The MENA region needs to invest over 7% of its GDP in the next five to ten years in order to fill the current infrastructure gap. These needs span large, but are more important in the sectors that are closely related to economic integration, namely, transport, energy, ICT but also the ones that provide basic infrastructure like water and sanitation (World Bank, 2020). These investments are needed to create new resilient infrastructure as well as to ensure the sustainability of existing infrastructure. Since the early 2000s, private investment in infrastructure has been increasing steadily across most regions with the exception of MENA. The region experienced a sharp decline in private sector participation in infrastructure investment in many countries in the region during 2010-12, particularly due to political instability of the Arab Spring.

While investment has since recovered to pre-2010 levels, this is primarily due to a few large energy projects in Morocco, Egypt and Jordan, while the transport and water sectors have seen very limited private sector activity. The principal sources of infrastructure project finance in the MENA region over the past three years have been multilateral and bilateral lenders, mainly been in the form of debt. International banks have also participated in a number of projects though always in conjunction with a multilateral lender or a major bilateral lender, while local commercial banks have only played a marginal role (OECD, 2017).

Proposal

A COORDINATED APPROACH FOR INFRASTRUCTURE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

To foster trade and investment and ensure a coordinated transition towards carbon neutrality in the two shores of the Mediterranean, a regional platform for co-operation and dialogue on investment for infrastructure connectivity is essential.

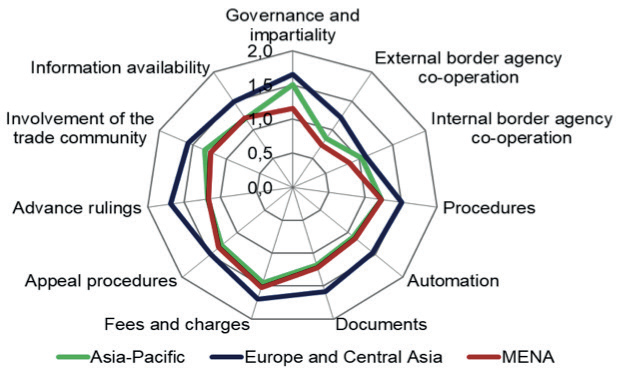

Such a platform should allow countries to work together to improve the regulatory and business environment necessary to attract more private investments in infrastructure. It should also entail co-operation on adopting common operational standards for infrastructure development to increase the quality and inter-operability of such infrastructure across the two shores. Such a regional platform would allow countries to define infrastructure in a more integrated and structured way taking into account regional integration as part of the design and development of infrastructure. An integral part of this is also the issue of policy harmonisation for trade facilitation in the region, which will only gain importance as the African Continental Free Trade Agreement will come into fruition and reduce cross-border tariffs to zero on many traded commodities. As viewed from the figure below, MENA region has a long way to go to ensure a fair and efficient intra-regional trade and a deepened trade symbiosis with Europe (see Figure 1).

A network of logistic platforms integrated in a cooperative framework should also be established when considering ports and special economic zones either in North or South Mediterranean, considering the comparative advantages between the two shores (such as differences in labour costs) and discrepancies in the quality of infrastructure. It is crucial to establish economic and cooperation agreements between ports and Special Economic Zones, to boost synergies and ensure an infrastructure development in those areas.

TOWARDS AN INTEGRATED LOGISTIC PLATFORM: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The rapid change in the configuration of global value chains in recent years could shortly turn into a game changer for the industrial development of the Southern Mediterranean region. Thanks to its geographical proximity, industrial potential and a young population and labour force, the region could make itself an attractive destination for companies looking to re-shore production from East Asia back to Western Europe and carry out near-shoring investments in the Mediterranean basin. This will require not only improving and upgrading infrastructure endowment of the region but also adapting its infrastructure networks and logistics to evolving global value chains dynamics.

One successful example of a country in the region that has adapted to such changes with investments in large infrastructure projects is Morocco. More particularly, the Al Boraq high-speed railway project has helped the country improve the connectivity of its main economic and commercial regions, rendering the country a Mediterranean corridor. The total investment has so far amounted to USD 7 billion.

Other projects in the Maghreb could also create a breakthrough for Mediterranean connectivity. For example, the on-going transportation network that revolves around Turkey-ItalyTunisia, creates an opportunity for an extended commercial connectivity that spans the wide area from the Maghreb to the Wider Black Sea. Despite these efforts, the region still faces some bottlenecks in transport infrastructure, a lack of multi-modal transport, and a fragmented port system.

Recent progress has improved transport infrastructure performances, but the level remains relatively low, causing higher trade costs and delays (see Table 2, which provides an analysis of the quality of trade, and transport-related Infrastructure). Such bottlenecks are a major constraint to trade and investment, limiting the growth of domestic and foreign manufacturing firms more than the lack of actual infrastructure. On average, 24% of firms in the MENA region identify transport issues as a major constraint to their business operations. In North African economies, the costs of port facilities are around 40% above the global norm, with long container dwell times, lengthy documentation processing, and delays in vessel traffic clearance (AfDB, 2019).

Currently, there are two maritime trends that will affect the competitiveness of Mediterranean ports and will have implications on the way infrastructure is developed. First, the concentration rate of the top four container carriers increased from 25% in 2002 to 50% in 2016, meaning that fewer big players would control most of trade flows, determining the competitiveness of Southern Mediterranean ports according to their location and ability to capture trans-shipment cargo (OECD, 2017). Second, the increase in the size of the ship (also called mega containerships) driven by the declining transports costs per ton, will put ports able to service large vessels at a competitive advantage, while also posing risks to global supply chains, such as the blockage of the Suez Canal by a 20,000 TEU container ship in March 2021 (OECD-ITF,2021).

Many ports in the region offer significant opportunities for foreign manufacturers looking for locations near markets in Europe, Middle East and Africa, but this potential is not realised in many countries. According to the IMF (2019), only a few ports are competitive by international standards, with Morocco leading the way with its Tangier port, which became a logistical hub for the region and is considered the biggest container port in Africa in terms of turnover. In Egypt, the Suez Canal is also expected to capture up to 25% of containerised Mediterranean trade (ibid). Such ports continue to facilitate internal and cross-border transport and trade and have an important role not only for the economic development of Egypt and Morocco, but also for the Mediterranean region (OECD, 2021a).

Case study 1: Reinforcing Egypt’s position in global trade through the Suez Canal Economic Zone

The expansion of the Suez Canal in 2015 to enhance Egypt’s position in global maritime trade was also followed by the creation of the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone) to exploit its potential for investment attraction and export-oriented growth. Such megaprojects are part of Egypt’s Vision 2030 to create jobs and achieve sustainable growth. The SCZone was established on 461 km² of land and six maritime ports strategically located along the international waterway with direct access to ports, to serve as an international logistics hub and areas for light, medium and heavy industry as well as commercial and residential developments. To effectively manage and supervise the zone development, a special autonomous authority called the SCZone Authority was subsequently formed.

The SCZone enjoys an autonomous legal framework with a business-friendly regime to attract international investments. The Authority has the mandate to manage and promote the SCZone, through state-of-the-art facilities and services as well as a variety of financial and non-financial incentives for investors willing to set up in the SCZone. It has executive powers of regulation and approval including the full authority to oversee all areas of operation, staffing, budget and funding, partnerships with developers and business facilitation services. Relevant ministries are also part of the SCZone Authority’s board (OECD, 2020).

The SCZone has recently developed a Strategy for 2020-25 to become an international investment hub and an export platform with a distinctive access to African markets. To support the implementation of this Strategy, the SCZone relies on several value propositions, namely the set-up and the ecosystem readiness, the regulatory framework, financial incentives, provision of services, and the cost advantage. The SCZone has four industrial zones (Sokhna, Ain Sokhna, Port Said, and Qantara West industrial zones), targeting various types of manufacturing investments within a wide range of industrial clusters. It does not have a sole focus on maritime-related services, but more generally on providing an attractive investment environment for medium, light and heavy manufacturing industries as well as higher value-added services such as renewable energies and information and communication technology. Other sectors that are targeted include pharmaceuticals, agribusiness, textiles and consumer electronics.

Case study 2: Tanger Med, an ambitious platform and a regional hub

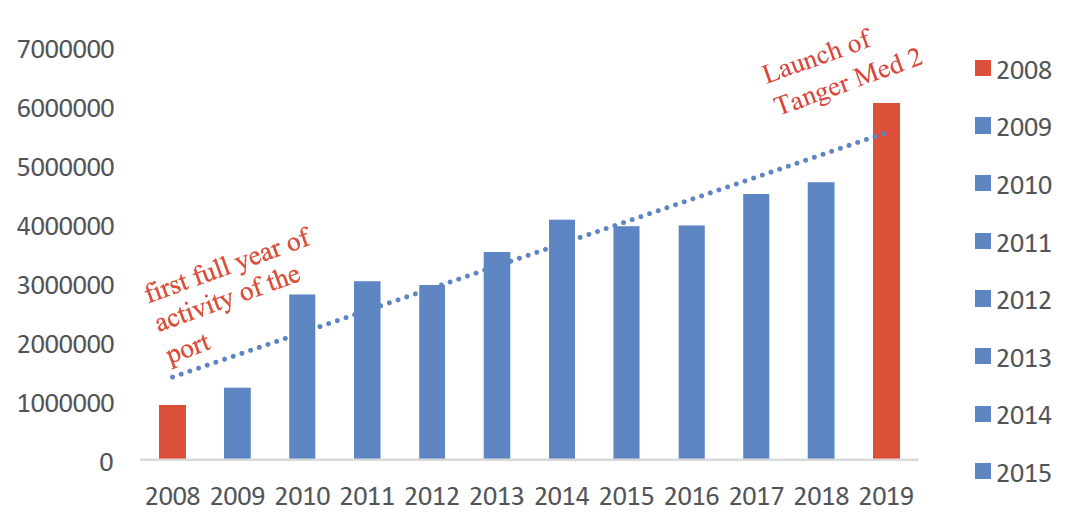

Situated 40km east of Tangier, Morocco, Tanger Med is the largest cargo port in the Mediterranean and in Africa by capacity. The port represents a major logistics and industrial hub and a gateway for Morocco’s imports and exports, connecting to 186 ports worldwide. It has a capacity of up to 9 million containers, a million cars and 7 million passengers1 (see Figure 2). It consists of a maritime port, Export Free Zones, a logistics platform and an industrial zone. A year after starting its activity in 2007, it had become a major platform in the Mediterranean Sea and in Africa. It has benefited Morocco through improving its logistics and its ranking in the UNCTAD Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, and has also extensively driven up the overall container traffic of Morocco (See Annex 1). As a result of the project, job creation in the region of Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceima grew three times faster than in the country as a whole, with an average employment growth of 2.7 per cent since its creation (World Bank, 2015).

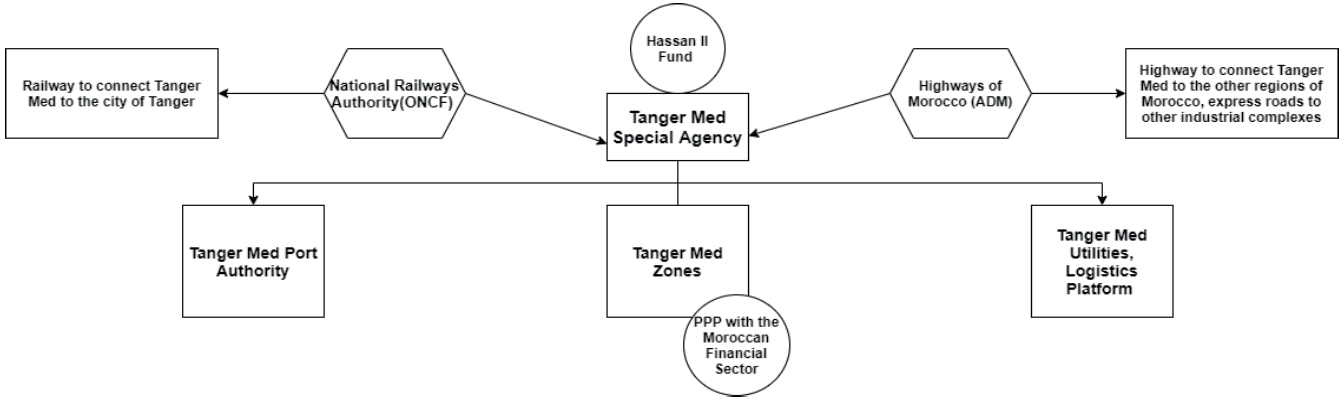

The project was handled by the Tanger Med Special Agency, a state entity. To attract the private sector, the Moroccan government also offered proper guarantees, adapting the contracts aligned with the objectives of all the stakeholders. Two of the subsidiaries of TMSA, namely Tanger Med Zones and the logistics platform operate closely with the private sector, through concessionary contracts. The container operations have also been subject to a public procurement for 30 years, won by two worldwide leading operators (Eurogate and Maersk). With simplified procedures, the free zones and the logistic platforms attracted more than a thousand operators, both nationally and internationally based (e.g. DHL, Bolloré logistics etc.). Such success has been due to several factors:

– Local development promoting national development. By choosing the north of Morocco as a hub for Morocco and Africa, Morocco has enacted a strategy of local development that helped create economic activity in the Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceima region. Investments have focused on extending highways and railways to improve the connectivity of the region, with a direct connection to other industrial hubs like Casablanca and Kénitra, as well as to the administrative capital of Morocco.

– Infrastructure as a vehicle of development. Morocco has built a strong expertise in large projects that allowed it to upgrade the quality of its infrastructure and better connect its different regions. With the ongoing and future projects, the country will reinforce its status as a Mediterranean hub and as a corridor of choice that will improve connectivity and business opportunities at the regional level and between Europe and Africa.

– Free Zones. Morocco improved its business climate to attract FDI by means of exemptions on the registration fees for land acquisitions, exemptions on license and urban taxes, temporary exemptions on corporate taxes (which is no longer the case) and no taxation or reduced taxation of dividends for foreign and domestic investors. TFZ is a designed one-stop-shop for investors. Morocco stands today as the main destination of foreign funds in Africa.

– Regulatory framework. The creation of TMSA by the means of a specific law has certainly signalled the strength of the project to the private sector. Indeed, as discussed above, the decree-law defined the exact prerogatives and delimited the space of action of TMSA, and set specific objectives for the agency (see Figure 3). Furthermore, the legal framework for public-private partnerships adopted by the parliament in 2014 strengthened the credibility and viability of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as public contractors backed by the underwriting of the state.

– An open project with foreign operators. With the means of the free zones and the regulatory framework, Tanger-Med could attract foreign expertise. This will have important spillover effects on the quality and the knowledge of the Moroccan product and the Moroccan know-how through technological transfers. The process of public procurement has also become more fluid and stronger, and serves as a vector of development.

THE POTENTIAL FOR ENERGY COOPERATION

Another fundamental field of cooperation between the two shores is energy. Despite being a peripheral demand market for energy, the MENA’s energy demand is expected to almost double by 2040 (Zelt et al., 2019). The region has one third of global oil and gas production and resources, as well as growing energy connections with Europe, particularly power interconnections and natural gas and hydrogen infrastructure (International Energy Forum, 2020). The European Commission estimates that total final energy consumption in the Southern Mediterranean could increase by 37 per cent by 2040, with one-half being driven by an increase in electricity consumption (SRM, 2020).

Currently, a number of sub-regional initiatives are in place to interconnect the electricity networks and allow for electricity trade among the MENA economies.2 Such initiatives have the potential to substitute for power generation and provide stability to the energy system of a country. While some of these electricity interconnections have existed for some time, their utilisation remains low particularly in the MENA and has only led to a modest electricity trade. Challenges include not only the lack of proper infrastructure but also the lack of a harmonised regulatory framework at the national and sub-regional level that would encourage competition and entry of private investors in the energy market (OECD, 2021b).

The electricity sector is largely dominated by SOEs, often with subsidies that make the price of electricity too low for investors to have any incentive to enter the market (World Bank, 2020). Numerous countries rely on line ministries as regulators, even if they often operate in the sector through SOEs. Separate regulators can help promote confidence about the regulator acting objectively and in a transparent way. Jordan and Morocco have been among the first to reinforce enabling conditions for investment in renewable electricity generation.

Today there are three important energy developments in the Mediterranean, which together can inaugurate a dynamic Mediterranean energy market. First, Morocco has become a renewable energy production powerhouse; second, the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum was established in Cairo in September 2020 with several countries striving to position themselves as regional gas hub. In this initiative, Egypt is currently the frontrunner. Third, hydrogen has emerged as an energy vector and it is now destined to complement electricity in the energy transition.

The recently released European hydrogen strategy will rely in part on electrolysis capacity in North Africa for the export of green hydrogen to Europe. In many aspects, hydrogen could become a game changer for the Mediterranean, and European financial support is clearly present to fund important projects of common European interest. However, North Africa should not only be considered as a source of abundant solar, wind and natural gas to be exported to Europe to satisfy its low-carbon energy requirements.

Unlocking North Africa’s huge energy potential will require much more than building and financing the requisite production and transportation infrastructure. To realise the vision for an integrated Mediterranean energy market, concrete policies and investments are needed:

– Energy carriers should not from being constrained by physical infrastructure: AI, pipelines, transmission cables have their own geopolitical baggage. To avoid this, it is necessary to promote well-functioning markets and price benchmarks for LNG, electricity, and low-carbon hydrogen.

– It is essential to empower energy-exporting countries to develop their own local energy ecosystems and competitive local end-use markets.

– Policies and incentives are required to enable local private sectors, including SMEs, to acquire three main skills: the capacity to develop projects in partnership with international private project developers; the capacity to deploy, operate, adapt, improve and reproduce imported technologies; and the capacity to invent new technologies and commercial solutions.

– It is necessary to create an incentive framework linked to the European Green Deal by which all Mediterranean economies can meet net-zero carbon emissions targets by 2050: this could include establishing a shared emission-trading system.

– There must be support for the development of open access multi-carrier energy hubs, facilitating energy trade within North Africa and the Levant and facilitating price interplay between natural gas and electricity.

– Finally, consideration could be given to the establishment with the G20 support of a Mediterranean energy infrastructure exchange or, at the minimum, a new energy infrastructure fund to be managed jointly by the European Investment Bank and regional financial institutions, to facilitate access to debt and equity capital for project developers and industry players and provide a mechanism for commercial lenders and institutional investors to recycle their capital.

WHICH REFORMS ARE NEEDED?

In order to promote investments in infrastructure that would help improve the economic partnership and bilateral trade between the two shores of the Mediterranean, a clear regulatory framework with broader governance reforms should be established in MENA countries. The G20 and international and regional development banks could provide investments and technical assistance to strengthen the regulatory context, increase the attractiveness for investments and make the procurement system more transparent and efficient. Addressing investment restrictions and competitiveness reforms is also urgent to unleash the potential of energy and digital market in the region, attracting new private investors. It is also crucial to blend public and private resources to attract more private investors and de-risk investments in infrastructure, which are characterised by high risks and low investment returns. Moreover, it is crucial to harmonise industrial and trade policies across regional countries and enhance higher education systems to develop the necessary skills to improve the business and regulatory framework.

Improving the regulatory framework for investment in infrastructure

One of the main challenges for developing infrastructure in MENA relates to the existence of administrative and legal bottlenecks that hinder the proper execution of projects and induce reluctance on the part of the private sector. Many countries in the region (e.g. Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt) have introduced specific PPP legislation that reduced the uncertainty faced by the investors (see the Moroccan Case study for example). They present different interesting models of how large projects could be built around the public and private sectors, and hence, help close the gap in infrastructure finance. While these improvements have led to a growth in PPPs in recent years, the region has also experienced and still facing periods of social and political unrest, which increase risks and reduce private investment.

Investment policies and the need for openness

Even though several economies in the MENA region are open to foreign investment, the level of restrictions remains higher than the OECD average, especially in infrastructure services and constructions. Algeria has the highest level of restrictions in all relevant sectors (except for surface transport). Jordan maintains fairly high restrictions in the transport sector, while the Moroccan economy presents restriction to foreign ownership in different domains, including air and maritime transport. In Egypt, the only framework allowing foreign investments in the maritime sector are joint ventures where the foreign equity does not exceed 49% (OECD, 2017a). In transport, provision remains dominated by the public sector, with some private concessions in ports and airports. Overall, such restrictions affect competition in the market and limit the quality-of-service provision.

Improving the governance of infrastructure could also attract more private investment

Good governance and strategic vision can improve the management of infrastructure projects and create the basis for increasing private sector participation in funding, construction and operation. For a number of countries in the region, developing infrastructure has come at high levels of capital expenditure, while the efficiency of public investment could be improved. Areas of public management improvement include strengthening the procurement, transparency, and appraisal and selection processes. Planning infrastructure development in a holistic way can help ensure efficient use and allocation of resources.

Cooperation on common standards to ensure better quality, compatibility and inter-operability of infrastructure networks across the region

Infrastructure cooperation is currently hindered by different national standards in the Mediterranean area, including among neighbouring MENA countries. Besides removing restrictions to investment and improving the regulatory environment, countries should cooperate to improve the quality, compatibility and inter-operability of infrastructure networks based international tools and instruments. While adhering to best-practice principles may be expensive in the short term, because infrastructure projects will have to meet higher standards of efficiency, safety and sustainability; however, they incur lower lifecycle costs than infrastructure with various standards at the country level, which could impose long-term costs.

Improving the capacity and efficiency of ports and ensuring connectivity with the inland areas

This includes reducing capacity bottlenecks and waiting times while also linking ports with rails and other multi-modal transport for better connectivity with large inland areas (OECD, 2021a). Successful policies have also focused on linking ports with well-developed special economic zones or research centres and universities, as well as building on trade agreements with local and external partners to facilitate movements of goods and services and develop linkages with global economic hubs.

Encouraging competition and entry of private investors in the energy sector

Many countries in the region are rich in renewable energy sources but have not sufficiently diversified their power supply. Although many have set up national renewable energy targets and the deployment of related projects is well under way, they expect to rely on gas and oil to generate electricity at least until 2030. Challenges include not only the lack of adequate infrastructure but also of the absence of a harmonised regulatory framework at both national and sub-regional level. The European Union could play a crucial role in providing technical support to its southern neighbours on harmonisation of regulations in the renewable energy sector.

Cooperation at the G20 level and with the EU

Cooperation in transport facilities has recently been enhanced through the revised EU Partnership for Southern Neighbourhood, which recognizes transport as a key component of policies and instruments supporting the development of the Southern Mediterranean. This is highlighted by the Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy, which aims to link transport infrastructure in the region through interoperability of rules and standards with the final goal of promoting transport policy reforms and creating maps of a future trans-Mediterranean transport network (TMN-T). This effort will boost investment and contribute to linking up Sub Saharan Africa, North Africa and Europe. In the energy sector, the EU Commission proposal for a Regulation concerning the revision of the TEN-E networks clearly considers the Southern Neighbourhood, when it fosters to link the Union’s energy networks with third-country networks, while at the same time ensuring shared standards for network interoperability. In particular, the Regulation proposal is intended to boost the identification of the cross-border projects and investments across the Union and its neighbouring countries that are necessary for the energy transition and the achievement of climate targets. It is important that the EU moves in this direction, possibly involving also other G20 countries, providing a set of shared environmental policies and standards that are adopted in both the shores of the Mediterranean, and ensuring sustainable logistics and investments in the region.

Drawing from the experience of regional and multilateral investment facilities, such as Invest EU, as well as with the support of initiatives such as the G20 Compact with Africa, a new common fund shared by the willing development banks of G20 countries could be created to attract private flows, and boost quality infrastructure investments in North Africa. This fund must be functional to achieve the priorities endorsed by the G20 summit, in the areas of climate resilience and sustainable transition, infrastructure maintenance and renewal, energy security, digital development and social inclusion.

ANNEX 1

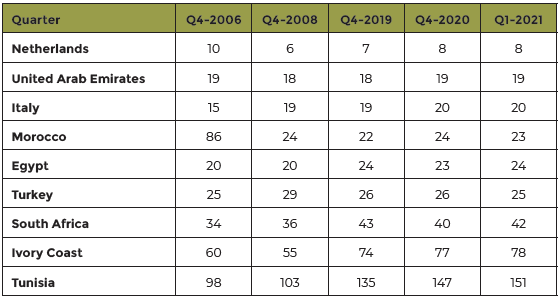

Table 1: Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, Selected Economies

Source: UNCTAD

Figure 1: OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, Regional Comparisons (2019)

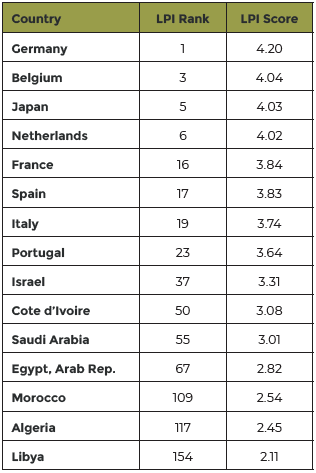

Table 2: International Logistics Performance Index, World Bank 2018

Figure 2: Container Port Traffic, Morocco Source: UNCTAD Stat, 2008-2019

Figure 3: Overview of TMSA Structure

NOTES

1 For a thorough presentation, see https://www.tangermed.ma/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Fiche-Clef-TANGER-MED-VENG-2020-1.pdf.

2 This includes the Maghreb regional interconnection project between Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia; and the Eight-Country and Territories Interconnection project between Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey and the Palestinian Authority.

REFERENCES

AfDB (2019). African Development Bank: African Economic Outlook: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/2019AEO/AEO_2019-EN.pdf

European Commission (2021). Renewed partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/joint_communication_renewed_partnership_southern_neighbourhood.pdf

European Commission (2020). Proposal Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on guidelines for trans-European energy infrastructure and repealing Regulation (EU) No 347/2013

IEA (2020). Data and statistics on renewable energy share in final energy consumption https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics?country=ALGERIA&fuel=Renewables%20and%20waste&indicator=SDG72

IMF (2019). Economic Integration in the Maghreb; An Untapped Source of Growth, IMF Departmental Papers / Policy Papers 19/01, International Monetary Fund.

International Energy Forum (2020). https://www.ief.org/_resources/files/events/4thief-eu-energy-day-the-green-new-dealand-circular-economy/03.-ivan-marten.pdf

Kulenovic, J.Z. (2015). “Tangier, Morocco: Success on the Strait of Gibraltar”. World Bank Blogs

OECD-ITF (2021). Stuck in the Suez Canal: Lessons from the Logjam. https://transportpolicymatters.org/2021/04/01/stuck-inthe-suez-canal-logjam-lessons/

OECD (2021), Middle East and North Africa Investment Policy Perspectives, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6d84ee94-en

OECD (2021a), Regional Integration in the Union for the Mediterranean: Progress Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/325884b3-en

OECD (2017) Supporting the Development of the Suez Canal Economic Zone: Suez Canal Needs Assessment Report and Action Plan. https://sczone.eg/uplibrary/Supporting-the-Development-of-the-SCZoneNeeds-Assessment-and-Action-Plan.pdf

Secrétariat Général du Royaume du Maroc, Décret-loi n° 2-02-644 du 2 rejeb 1423 (10 septembre 2002) portant création de la zone spéciale de développement Tanger-Méditerranée. Bulletin Officiel n° 5040 du Jeudi 19 Septembre 2002.

SRM (2020). Italian and MED Energy Report 2020. https://www.srm-med.com/p/meditalian-energy-report-2019

WEF (2019). http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-report-2019/competitiveness-rankings/#series=GCI4.A.03

WEF (2017). https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/05/what-you-need-toknow-about-the-middle-easts-start-upscene-in-five-charts/

World Bank (2020). Jordan: A pioneer in investing in its PPP capacity. https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/jordan-pioneer-investing-its-ppp-capacity

World Bank (2019), MENA Economic Update: Reaching New Heights: Promoting Fair Competition in the Middle East and North

Africa, World Bank, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1504-1

Zelt, O.; Krüger, C.; Blohm, M.; Bohm, S.; Far, S. Long-Term Electricity Scenarios for the MENA Region: Assessing the Preferences of Local Stakeholders Using Multi-Criteria Analyses. Energies 2019, 12, 3046.