Efforts to monitor and regulate BigTech companies have been fragmented, both globally and across economic sectors. We advocate for a change in the regulatory paradigm to create a framework that will accommodate the different priorities of countries, support inter-jurisdictional coordination, and minimize the risk of regulatory fragmentation.

In this policy brief, we identify the main issues listed by regulators from developed and less developed countries and group them around three dimensions:

- Capital access, which includes financial inclusion and financial stability

- Market structure, which includes market efficiency and antitrust regulation

- Consumer experience, which includes consumer welfare and data usage

These classifications help reframe the policy discussion, showing how the issues are related and how they are, or will be, relevant for most countries, depending on their level of economic and infrastructure development.

Challenge

Understanding and monitoring BigTech activities in finance or as third-party service providers is a looming challenge for financial authorities. The global reach of these firms underscores the importance of international coordination. Debates on financial stability, competition, and data rights, will soon converge, crossing national jurisdictions such as China, Japan, the E.U., and the U.S. That is why we urge the G20 to define a comprehensive vision and agenda to coordinate global monitoring and regulatory efforts regarding BigTech.

Financial technology (FinTech) has had no impact on financial stability thus far, but this could change quickly as large, established technology companies (BigTech) become more deeply involved in the industry. The BigTechs are the U.S.-based technology firms Google, Amazon, and Facebook, and the Chinese-based firms Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei (GAFTAH). While each company is well known for dominating at least one market—be that e-commerce, social media, or online searching—their role in the economy is greater still. Following the definitions proposed by the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund, and the Financial Stability Board (BIS 2019; IMF 2019; FSB 2019), the platform-centric business models of BigTech distinguish them from other businesses. These digital platforms are themselves facilitated by an inordinate amount of user data, and they are reinforced by strategic investments outside of the company’s primary economic sector.

The BigTechs offer many potential benefits: their low-cost business structure can easily be scaled up to provide essential financial services, especially in places where a large portion of the population remains unbanked. Using big data and analysis of the network structure in their established platforms, they can assess the riskiness of borrowers, reducing the need for collateral to assure repayment.

Yet, their business model creates a unique set of risks to financial stability, beyond the standard financial risks derived from leverage, maturity transformation and liquidity mismatches, or operational risks. The presence of BigTech in finance creates new and complex trade-offs between financial stability and financial integration, between competition and market efficiency, and between consumer welfare and data usage. The main challenge for regulators is to understand how BigTech activities spread across different sectors and jurisdictions, whether geographic or regulatory.

Proposal

Building on the different topics identified by regulatory authorities and advisory panels from Asia, North America, South America, and Europe, this policy brief proposes a novel approach to the policy discussion. Its main goal is to show how different issues are related, which will facilitate the emergence of a global policy framework at the G20 level (Lopez and Smith forthcoming). It focuses on three main axes: capital access, market structure, and consumer experience.

The policy brief provides a road map on how to bridge the gap between different regulatory approaches that tend to focus on country-specific characteristics. It highlights the trade-offs within each axis: between financial inclusion and financial stability (capital access), between market efficiency and antitrust regulation (market structure), and between consumer welfare and data usage (consumer experience).

Structuring the policy agenda around these essential pillars when addressing G20 priorities, such as how to shape new frontiers and empower people, is a necessary step to designing a global regulatory framework. This will ensure that the framework will be relevant for most countries while minimizing regulatory segmentation and inefficiencies.

What is so special about BigTech?

The rise of technological innovations in the financial sector could lead to a more efficient and resilient financial system. Indeed, the presence of BigTech and FinTech will enhance competition and diversity within financial services. Both stand to enhance the efficiency of financial services provision, promote financial inclusion, particularly in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), facilitate access to financial markets for small and medium-sized enterprises, and allow associated gains in economic activity. However, they also might affect financial stability by changing the market structure for financial services. Furthermore, these platforms are ecosystems connecting financial services to other non-financial activities and a wealth of information.

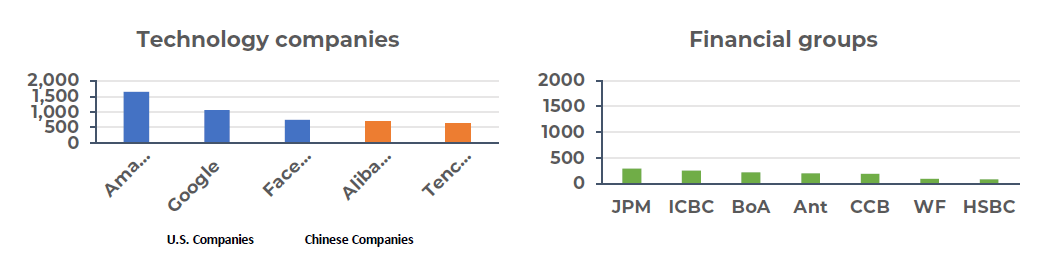

As shown below, the BigTechs are larger than all the major financial groups defined as systemically important financial institutions after the 2008 financial crisis.[1]

i) Access to large amounts of data

ii) Positive network effects

iii) Interwoven business activities

Leveraging their access to data, capital, and technological expertise, BigTech companies provide unique solutions to societal problems, solutions which were not available before. These range from helping American authorities with the coronavirus crisis to improving broad access to the internet in EMDEs.

These new business models have led to a gain in efficiency that has benefitted consumers and businesses across the world, but they also expose the world to new forms of risk. If unmonitored, these risks could accumulate and destabilize the financial system and, more broadly, societies. Thus far, existing regulatory authorities have not been able to implement such monitoring due to the lack of a relevant framework for the multi-sectoral and global nature of BigTech business models. The efforts of these authorities have led to a fragmented set of regulatory initiatives, which gives rise to the question: can they be reconciled to derive an inclusive and global framework?

How to assess the trade-off between risks and benefits when it comes to BigTech?

Regulatory authorities and advisory panels from Asia, North America, South America, and Europe have raised several issues when it comes to BigTech. Most of these show a clear geographic divide, especially between developed and less developed countries. We recommend shifting the existing policy paradigm toward a more inclusive framework by sorting the identified issues around three essential dimensions: capital access, market structure, and consumer experience.

The resulting assessment of the trade-off between risks and benefits accounts for the country- and industry-specific needs. The systematic use of this classification system during all G20 discussions in which BigTech currently plays, or will play, a major role is essential. Indeed, the size and multidimensional nature of BigTech companies make them relevant to many of the G20 priorities, namely:[2]

- Unleashing access to opportunities

- Women’s empowerment

- Enabling person-centered health systems

- Boosting the financial inclusion of women and youth

- Enabling the digital economy

- Finding a global solution to tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy

- Utilizing technology in infrastructure

- Developing smart cities

- Addressing the entry of BigTech in finance

- Combatting corruption

How does it work?

Capital access: Financial inclusion and financial stability

Financial inclusion and financial stability are both related to the fact that some BigTechs provide access to capital for a broad, usually underserved population.

EMDEs often identify financial inclusion as the main benefit of BigTech involvement in financial services. BigTech companies rely on their abilities to pool, process, and use pertinent information to provide financial services to untapped populations. Consumers can use smartphones and free internet access to open bank accounts, pay for goods electronically, and apply for loans. Regulatory authorities and advisory panels have studied cases in Latin America, Asia, and Africa to identify the mechanisms at play. The most well-known examples are:

- Argentina-based MercadoLibre, which leverages its access to a vast amount of consumer data, made available through its core e-commerce business, to offer personal and business loans to households across Latin America (BIS 2019).

- In China, tech giants Alibaba and Tencent have improved credit access for a large part of the population that lacks a traditional credit history (IIF 2018; IMF 2019; FSB 2019).

- In Kenya and India, M-Pesa—an affiliate of the U.K.-based telecommunications firm Vodafone—provides mobile payment services to over 32 million people (IMF 2019; FSB 2019).

Yet, this increased connectivity between financial services and other parts of the economy, outside of any monitoring, has led financial regulators to raise concerns about the potential impact on financial stability.

While the applications differ across countries, the risk lies in the critical role BigTech plays in this new type of network (FSB 2019).

- In developed economies, the strategic partnerships between BigTech companies and incumbent financial institutions have created potential weak points. A BigTech company may provide a third-party service to incumbents (such as Capital One using Amazon Web Services) or offer a financial service through its own digital platforms with the incumbent financial institution managing the back-end delivery (such as Apple partnering with Goldman Sachs on the Apple Card). A single disruption to the BigTech company—for example, a cloud computing service blackout— could have downstream effects on incumbent financial institutions, magnifying the risk to the broader financial ecosystem.

- In EMDEs, the financial stability risk is more commonly associated with a single BigTech company dominating the provision of a financial service and the lack of alternative providers who could pick up the slack in the event of a disruption. China’s reliance on Alibaba and Tencent illustrates this point. The money market fund owned by Alibaba is one of the world’s largest, with over $235 billion AUM as of November 2018 (IIF 2018; FSB 2019). A sudden loss of consumer trust in Alibaba could lead to a mass exodus of deposits, with the potential to disrupt the entire interbank funding system in China (IIF 2019; FSB 2019).

Depending on its level of development, a country will prioritize financial integration over financial stability and vice versa. Yet, the importance of cross-border activities requires the emergence of a global framework.

Market structure: Market efficiency and antitrust regulation

A country needs infrastructure (physical and virtual/digital) to drive the effects of BigTech companies on its market structures and regulatory focus.

EMDEs regulators and international organizations have appreciated the efficiencies brought by BigTech companies to domestic markets, leading to lower costs, improved quality of goods and services, and increased capital investment in research and development. There are numerous illustrations of how BigTech’s strong economies of scope and scale is beneficial to EMDEs as well as other countries. In China, Alibaba was instrumental in the expansion of the freight and logistics infrastructure to rural areas, a necessary step to gaining access to China’s mostly untapped consumer base (IIF 2018). In the US, cloud computing services lower costs for existing firms, including small and medium-sized businesses, leading to greater flexibility and scalability in their business models (FSB 2019).

In contrast, antitrust regulators in developed economies focus on the lack of competition inherent with the dominant position of the BigTech companies in some markets. BigTech companies’ ability to invest large amounts of capital into new technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, allows them to increase their offering of products and services while controlling the associated costs (Zingales and Lancieri 2019; Digital Competition Expert Panel 2019). While acknowledging the efficiency gains, European officials have raised concerns on several issues associated with BigTech, such as killer acquisitions (Digital Competition Expert Panel 2019), limitation of consumer freedom, and manipulations of the consumer decision-making process (Zingales and Lancieri 2019).

Once again, the level of development in a country plays a key role in its regulatory agenda related to market structure. However, the European antitrust authorities dominate the regulatory efforts in that domain and may end up driving the global regulatory standards.

Consumer experience: Consumer welfare and data usage

Both the dimensions previously discussed, namely capital access and market structure, rely on accessing and processing data collected from the customer.

The benefits are unquestionable. Beyond financial inclusion, consumers, and more specifically, family dyads, benefit from the presence of BigTech companies in the remittance system. In Asia, Alibaba’s entry into the sector has enhanced the remittance system that connects migrant families in the Philippines and Hong Kong. The firm’s subsidiary, Ant Financial, provides remittance services that are cheaper and quicker than the ones offered by traditional financial institutions (BIS 2019). It is worth noting that consumers in Africa and Asia tend to trust telecommunications and social media companies for financial transactions more than regular banks (IMF 2019).

Investments in technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning also benefit consumers and companies by facilitating the identification of fraud and other criminal activities. For example, Chinese BigTech companies have applied artificial intelligence to facial recognition software to identify and deter identity theft and other fraudulent applications of personal data (IIF 2018).

However, BigTech’s usage and management of consumer data have been a concern for regulators, mainly from Europe and the U.S. The issues raised range from digital authoritarianism (IIF 2018), systematic bias in the financial services sector (ICMB 2019; CEPR 2019), data privacy and data ownership rights (ICMB 2019; CEPR 2019), and the spread of misinformation (Zingales and Lancieri 2019).

Data access, usage, and management are at the core of the BigTech business model. The improved access to services, financial and otherwise, for underserved populations, often in EMDEs, relies on accessing and processing customer information. Yet, most of the regulatory efforts related to data protection come from Europe. Without international discussion on the topic, the European standards may define the global ones.

The impact of BigTech differs across sectors, countries, and levels of development. Hence, there is a need for a comprehensive, globally coordinated framework for monitoring and regulating BigTech companies and their entry into finance.

Recommendation

Thus far, regulatory efforts have been mostly country specific, which has led to a fragmented set of initiatives.

In this policy brief, we advocate for the grouping of the main issues identified by regulators across the world around three dimensions:

- Capital access, which includes financial inclusion and financial stability

- Market structure, which includes market efficiency and antitrust regulation

- Consumer experience, which includes consumer welfare and data usage

Using these three dimensions to frame the discussion around monitoring and regulating BigTech will lead to the design of a framework that accommodates the different priorities of each country, supports inter-jurisdictional coordination, and minimizes the risk of regulatory fragmentation.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

BIS (Bank for International Settlements). 2019. “Big Tech in Finance: Opportunities

and Risks.” BIS Annual Economic Report 2019. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2019e3.pdf.

Digital Competition Expert Panel. 2019. “Unlocking Digital Competition: Report of the

Digital Competition Expert Panel.” March 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf.

FSB (Financial Stability Board). 2019. “BigTech in Finance: Market Developments and

Potential Financial Stability Implications.” December 9, 2019. https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P091219-1.pdf.

ICMB (International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies) and CEPR (Center

for Economic Policy Research). 2019. “Banking Disrupted? Financial Intermediation

in an Era of Transformational Technology.” October 2019. https://www.cimb.ch/uploads/1/1/5/4/115414161/banking_disrupted_geneva22-1.pdf.

IIF (Institute of International Finance). 2018. “A New Kind of Conglomerate: BigTech

in China.” November 2018, https://www.iif.com/Portals/0/Files/chinese_digital_nov_1.pdf.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2019. “The Rise of Digital Money.” July 12, 2019.

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fintech-notes/Issues/2019/07/12/The-Rise-of-Digital-Money-47097.

Lopez, Claude and Benjamin Smith. Forthcoming. “It’s Bigger than Big Tech: A

Framework to Understand the Economy of Tomorrow.” Milken Institute.

Zingales, Luigi, and Filippo Maria Lancieri. 2019. “Stigler Committee on Digital

Platforms” Policy Brief.” September 2019. https://research.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/policy-brief—digital-platforms—stigler-center.pdf.

Appendix

[1] . Notes: Stock market capitalization as of 18 August 2020, in billions USD. Ant = Ant Financial; BoA = Bank of America; CCB = China Construction Bank; ICBC = Industrial and Commercial Bank of China; JPM = JPMorgan Chase; WF = Wells Fargo. The estimated valuation of Ant Financial was derived from the amount raised in the company’s most recent funding round times the stakes sold. Huawei is not included due to insufficient valuation data.

Sources: Milken Institute Research Department; Pitchbook; S&P Capital IQ

[2] . These are part of the G20 Saudi Arabia 2020’s priorities.