The pandemic highlighted existing social and economic fault lines and exacerbated inequality, poverty, and marginalization. Simultaneously, climate change and environmental degradation present significant and growing risks. Transforming economies and social protection systems to support sustainable recovery and future fitness requires addressing the multiple and intersecting factors that shape people’s needs, opportunities and outcomes, and the interrelationships between social, economic, and environmental considerations. Disaggregated data that integrates these considerations are often not available. Investment in such data will enable responsive, modernized social protection systems that leverage the fullest potential of societies in support of sustained recovery.

Challenge

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted existing social and economic fault lines and exacerbated wealth inequality, gender inequality, poverty, and marginalization. Simultaneously, it transformed social protection needs, demonstrating the importance of social protection for delivering minimum standards of living for the physical, economic, and mental well-being of citizens.

At the same time, climate change and environmental degradation are increasingly recognized as among the largest risks facing the global community this decade (World Economic Forum, 2022). These risks are gendered, and their implications are borne disproportionately by those with fewer resources. Increased frequency and severity of climate-related shocks are already testing social protection systems.

It is essential to calibrate social protection to meet people where they are, for inclusion and access, quality (particularly effectiveness and efficiency), and legitimacy. This requires social protection systems responsive to differences in people’s circumstances and the factors that shape them (e.g., gender, age, disability, ethnicity) and holistic—integrating social, economic, and environmental considerations. Achieving this requires a robust, holistic evidence base integrating these considerations.

Such an evidence base is significantly lacking. Part of the problem is the under-resourcing of gender data (Baidee et al., 2021. In some cases, methodological flaws and gaps persist because they are integral to the measurement approach itself. This is the case for household-level measurement of poverty and inequality, which systematically ignores the estimated one-third of global inequality that resides within households, significantly undercounting global poverty and inequality (Kanbur 2016). It also over-estimates the extent to which improvements in GDP translate into improved outcomes for individuals. This contributes to a disconnect between improvements indicated by official poverty data and ground-level perceptions (Kanbur 2010: 41-70, 132). Sustained distance between understandings of policy makers and lived experience can erode citizen confidence in governments—with implications for legitimacy and social cohesion.

Furthermore, household-level data cannot be accurately disaggregated by key demographics of interest. For example, it is not possible to determine the relationship between gender and poverty from routine global poverty data (Cozzarelli and Markham 2014, World Bank 2017: xx, 114, 115), nor undertake intersectional analysis to understand how factors such as gender, age, disability or ethnicity concurrently shape circumstances.

Finally, existing poverty measures typically focus on money (the International Poverty Line, various national poverty lines) or a relatively narrow range of dimensions (the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index assesses deprivation in three dimensions using ten indicators)[1]. While important, these are insufficient to capture what people with lived experience of poverty identify as its defining domains (Wisor et al., 2014). Without an evidence base that captures the range of barriers to, and enablers of, human flourishing, the potential of social protection systems to contribute to COVID-19 recovery and respond to future shocks will remain under-realised.

Proposal

Establishing the foundations for inclusive and responsive social protection

Social protection systems and safety nets aim to protect and support vulnerable individuals, ameliorate material poverty, narrow inequality, enable individuals to contribute socially and economically, and support the social contract between citizen and state. Accurately and comprehensively identifying who requires access to social protection is a foundation for inclusion and coverage, particularly in the absence of universal approaches such as a universal basic income. This requires measurement systems that can accurately and comprehensively identify people in need of social protection.

However, data limitations have created challenges for understanding the gendered impacts of COVID-19. UN Women noted that “the limited availability of data is leaving many questions unanswered” (UN Women 2020). The World Bank assessed that “the foundation for designing effective policies that benefit women and men, girls and boys, gender data, is often incomplete, methodologically flawed, or completely lacking” (Bonfert et al., 2022).

This points to the importance of a “build back better” approach, including social protection systems that are responsive, inclusive, and effective. This, in turn, requires data that can reveal the factors influencing the circumstances of specific cohorts and any patterns of difference across social and economic groups and geographies.

Strengthening the availability of such data requires changes to current measurement approaches and data collection priorities.

Individual-level, gender-sensitive, and multidimensional measurements of poverty and inequality can illuminate the circumstances of particularly vulnerable groups, patterns of deprivation and inequality, strengthening the evidence base to shape social protection systems that are inclusive and better targeted.

The relevance of individual-level, gender-sensitive, multidimensional measurement for understanding intersectional inequality and the distribution of multiple and overlapping deprivations has been acknowledged (UN Women 2018, UN Women, UNSD 2020). The importance of such data as the foundation for gender-responsive social protection was reflected in a specific recommendation by the 2018 Expert Group Meeting on social protection in preparation for the 2019 session of the Commission on the Status of Women:

Ensure that data collection, planning, monitoring, and evaluation are gender-responsive, includes the generation and use of qualitative and sex-disaggregated quantitative data, and recognize women’s positioning within diverse family forms and communities and the multiplicity of their roles across the life course, including as carers, workers and active decision makers. (UN Women 2018: 11)

The need for individual-level, gender-sensitive, multidimensional measurement of poverty and inequality has an established lineage in international architecture

The 1995 Platform for Action arising from the Fourth UN World Conference on Women included Strategic objective A.4 “Develop gender-based methodologies and conduct research to address the feminization of poverty.” This identified the following specific actions to be taken by national and international statistical organisations:

68 (a) Collect gender and age-disaggregated data on poverty and all aspects of economic activity… to facilitate the assessment of economic performance from a gender perspective; (United Nations 1995: 25)

The Sustainable Development Goals and the overarching commitment to “leave no one behind” have underpinned an increased emphasis on disaggregated data. The Interagency Expert Group on the SDGs supports ongoing methodological development via a dedicated work stream on disaggregation and recognises that in some cases, multiple levels of disaggregation (e.g., by gender and age) may be needed (UN Statistical Commission 2019). The UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) is leading regional statistical development to accelerate the production of disaggregated data. Its report to the 2019 UN Statistical Commission included a specific recommendation on “strengthening national statistical capacities to design, collect, access and publicly disseminate high-quality, reliable and timely data disaggregated by sex, age, income, and other characteristics relevant to national contexts” (UN ESCAP 2019: 12).

The report of the 2019 High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development recognised that the invisibility of key populations due to data gaps is holding back progress, noting that “Investment in data and capacity is also needed for the adequate measurement… If the most vulnerable are not visible in statistics, there will not be appropriate policy action” (UN Economic and Social Council 2019:4, emphasis added).

In relation to the measurement of poverty and inequality specifically, the World Bank has recognised the need for individual-level measurement. It convened a workshop in 2017 to consider existing initiatives[2] and consolidate thinking, and acknowledged the relevance of individual-level poverty measurement in its 2018 Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report:

The common approach [to determine how many children, women, and men are poor] assigns all individuals within a household to the same poverty status as the household. However, this masks the potential differences in poverty among household members. Ignoring these decreases the effectiveness of common approaches to targeting poverty reduction interventions and the take-up of these interventions because they do not address the needs and constraints of the poorest individuals…

The accumulated evidence of numerous studies and data sources suggests that women and children are often disproportionately affected by poverty. (World Bank 2018: 125)

The World Bank also identified the need for better insight into within-household differences:

There is evidence from studies in several countries that resources are not shared equally within poor households….

We need more comprehensive data to deepen our understanding of how poverty affects individuals and to assess how social programs can be better tailored to meet their needs. The initial findings of this approach suggest that current assistance programs risk missing many poor people who are hidden in non-poor households. (World Bank 2018: 6-7)

And provided clear support for the insights delivered by multidimensional poverty measurement:

As we seek to end poverty, we also need to recognize that being poor is not just defined by a lack of consumption or income. Other aspects of life are critical…This expanded “multidimensional” view reveals a world in which poverty is a much broader, more entrenched problem, underlining the importance of investing more in human capital. (World Bank 2018: 5)

The Report of the 2019 UN High Level Political Forum also recognised that addressing inequalities requires data that goes beyond money-based poverty metrics:

27.(c) Inequality is about more than income and wealth. Actions must address inequalities in education, health, work, voice, agency (i.e., freedom of choice), housing, infrastructure and exposure to impacts from climate change, among other aspects of leading a dignified life. (UN Economic and Social Council 2019: 7)

Existing methodologies such as the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) have enabled progress on multidimensional measurement by providing a methodology for working from existing household data. However, this also necessitated a focus on a relatively narrow range of dimensions (3) and indicators (10) compared to what people with lived experience of poverty say matters (Wisor et al., 2014).

Shifts towards an individual-level, gender-sensitive, multidimensional measurement of poverty and inequality are being reflected in guidance and directional documents. The UN Women/Pacific Community Roadmap for Gender Statistics in the Pacific included the Individual Deprivation Measure[3] as a “specialized survey that addresses gender data gaps” and implementing it is a country- and regional- level indicator towards the Roadmap (SPC/UN Women 2020). UN Guidelines on the Production of Statistics on Asset Ownership from a Gender Perspective now recognise that household-level measurement of assets is problematic and recommend individual-level measurement to better calibrate policy related to the empowerment of women, reducing poverty, and understanding livelihoods (UN Statistical Division 2019: 3).

Several governments are also emphasising the use of disaggregated data in gender analysis to inform gender-responsive action on poverty and inequality in their development or foreign policy approaches and frameworks. This includes the USA (USAID 2015), the UK (DFID 2016), Australia (DFAT 2016, 2017), Canada (CIDA 2017), and Sweden (SIDA 2018).

Support for disaggregated, gender-sensitive data about poverty and inequality is also evident in thinking informing G7 deliberations (Gender Equality Advisory Council 2018).

Standards and expectations in support of individual-level measurement, gender-sensitivity and within-household measurement are gaining strength, providing a supportive context for accelerating change.

A fit-for-purpose individual-level measure of poverty

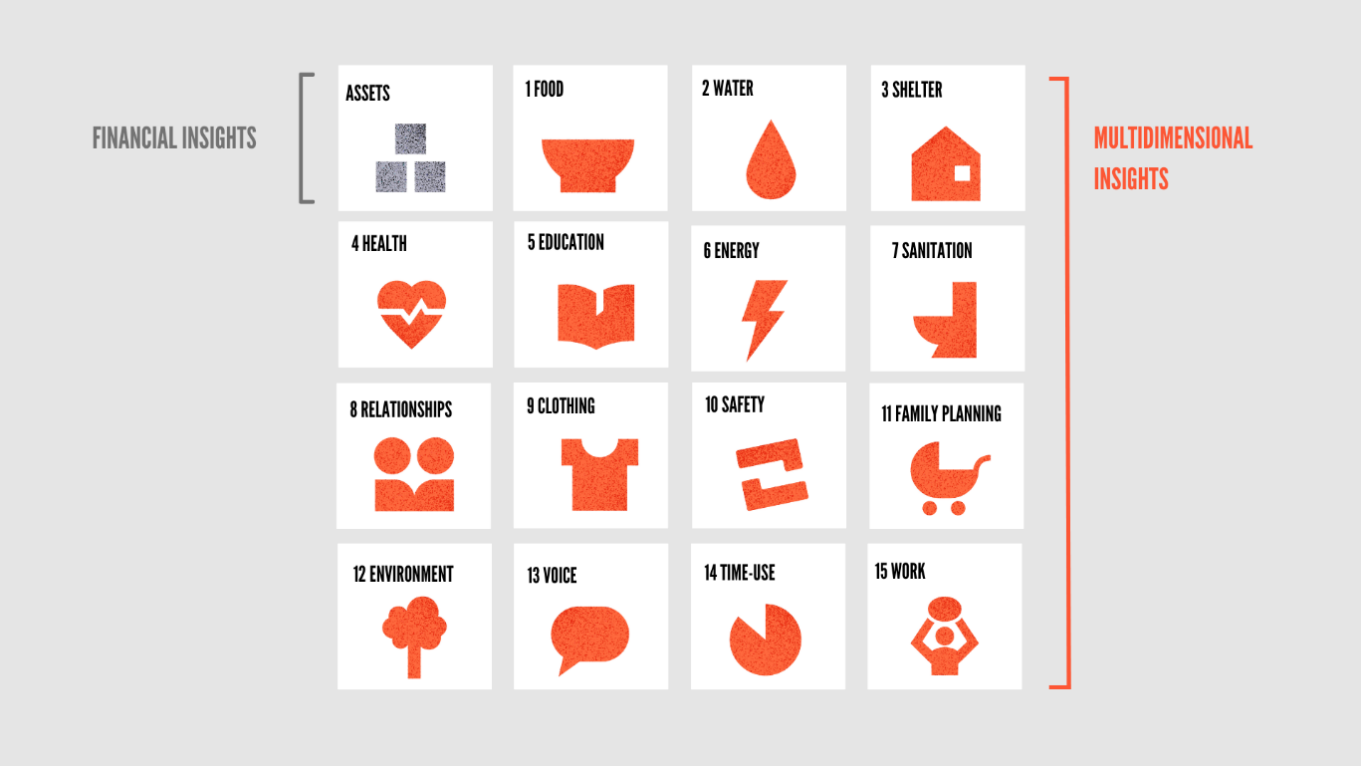

Until recently, a robust, feasible, individual-level measure of multidimensional poverty was unavailable. However, in 2020, the International Women’s Development Agency and the Australian National University concluded a multi-phase, multi-partner international research collaboration[4] to develop, test, and refine an individual-level, gender-sensitive, quantitative measure of multidimensional poverty, and address the limitations of household-level poverty measurement. Development began in 2008 with participatory research in six countries[5], to ground the measure in lived experience of poverty. The result was the Individual Deprivation Measure, a new quantitative measure of poverty that assesses fifteen dimensions of life—health, water, food, shelter, sanitation, clothing, safety, family planning, voice, energy, relationships, environment, education, time-use, and work—plus assets to separately assess financial circumstances (Wisor et al., 2014). The Australian Government’s subsequent investment in further refinement (Bessell et al., 2018), expert review and input, and testing in six countries helped to ready the measure for wider uptake. Global experts in composite measurement have audited the methodology and assessed it as coherent, robust, and appropriate (Caperna and Papadimitriou 2020).

In August 2020, IWDA launched Equality Insights as a flagship program to take this work forward.

The combination of what is measured and how delivers powerful new insights into material, social, economic, and environmental factors shaping poverty and inequality. Primary data collection from individual adults makes possible analysis by gender, age,[6] disability (via the Washington Group Short Set questions), socio-cultural background, marital status, number of children, rural/urban, other characteristics as relevant, and intersections of these.[7] This makes it possible to see the implications of overlapping barriers, and how patterns of deprivation vary (Fisk et al 2020). Sampling every adult in a household enables analysis of disparities inside households (UNECE 2019). Within-household analysis can identify the “invisible poor”,[8] the proportion of a population and its demographic make-up, who live in better off households, but are individually deprived (Crawford et al., 2021). Understanding within household differences is also important for accuracy and completeness given an estimated one-third of global inequality lives within the household (Kanbur 2016).

Early use also confirms the measure’s practical relevance. For example, in May 2020, as the impacts of COVID-19 and responses to it started to be felt in the Pacific, IDM data informed briefing on the likely implications of COVID-19 in Fiji to the Government’s COVID-19 Response Gender Working Group. IDM data from Indonesia and South Africa informed targeted briefing on anticipated gendered impacts of COVID-19 in those countries. In 2021, data from the Solomon Islands supported the Ministry of Women Youth Children and Family Affairs in the Solomon Islands to develop a first-ever gender and women’s policy for Central Islands province (IWDA 2022).

In 2020-2021, with funding from the Australian Government and philanthropy, the survey was adapted for remote delivery in the COVID-19 context (Meinhart and Russell, 2022) using Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI). While maintaining coverage of 15 key dimensions plus assets, Equality Insights Rapid provides a shorter, red-flagging tool to understand where needs and vulnerabilities are greatest.[9] Data collection occurred in Tonga and Solomon Islands in May-June 2022. Analysis will be available in late 2022.

Costs, contributions, and capabilities

Costs and cost-effectiveness are key considerations when determining data collection priorities. In 2020, the costs of Equality Insights’ predecessor, the IDM, were found to be comparable with other multi-topic surveys, and its methodology cost effective compared to a simple random sampling of individuals (Development Initiatives 2020a).

Assessing contributions, not just costs, is important in determining the value of individual-level, gender-sensitive measurement of multidimensional poverty, compared to household-level measurement. An independent evaluation (Development Initiatives 2020b) concluded that the survey makes a unique contribution to the poverty measurement and gender data ecosystem with relatively little overlap with other surveys and can highlight outcomes for groups that often face greater risks and vulnerabilities. An independent review of the sampling strategy (Social Research Centre 2020) concluded that collecting data from multiple household members does not produce redundant information as individuals within households differ significantly across multiple economic, social, and material domains.

Costs of introducing any new survey need to be managed. Particularly for low- and middle-income countries, measurement modernisation and innovation may require rationalising existing data collection. One option is alternating individual-level and household-level poverty surveys, initially. This maintains continuity with existing data while enabling the additional insights offered by disaggregated gender-sensitive data.

Additionally, building the capacity to use measurement innovations is key to realising their potential. Integrating learning and training with existing statistical training contributes to system strengthening and coherence. Comprehensive training for enumerators in the Equality Insights survey is provided prior to data collection. As with any survey, tablet administration and active data monitoring help to reduce measurement and data entry errors. Training for users and producers of the new Equality Insights Rapid data in Tonga and Solomon Islands will build from and integrate with UN Women’s existing curriculum on gender statistics. A web-based data platform will support wider data access and enable Equality Insights data to be utilised by data aggregation platforms.

Fully leveraging the benefits of measurement innovations such as Equality Insights while minimising trade-offs requires tackling the broader issue of funding adequacy. Increased funding for development data will enable the achievement of other development priorities (Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data 2018). Practical strategies and roadmaps exist to achieve this, including routine integration of data requirements in policy and program initiatives, and dedicated resourcing of gender data in national statistical budgets (ODW et al 2022).

The opportunity for G20 leadership

As the G20 develops policy settings to reverse the impacts of the pandemic and build back better, centering poverty, inequality and marginalization is critical. Improving the availability of individual-level, gender-sensitive data about multidimensional poverty and inequality is a foundation for strengthening the inclusion, coverage, and effectiveness of social protection systems. It provides evidence to inform more targeted and responsive policies, programs and resource allocations, and evaluate how these are translating into improved lives.

Measurement should recognize and help make visible the gendered elements of poverty. To do otherwise discounts dimensions that define women’s experience of poverty, such as sanitation, time-use, family planning and voice. Tools and approaches now exist to produce this data, and two of the eight[10] available data sets are for G20 countries—Indonesia and South Africa.

Leadership from the G20 to improve individual-level, gender-sensitive multidimensional data on poverty and inequality is aligned to the Group’s focus on accelerating recovery, reducing inequalities and strengthening inclusion. Enabling better insight will support the design of social protection systems that are simultaneously more targeted and more inclusive, maximizing the transformative potential of these systems.

The G20 can lead change by taking the following specific actions:

- Commission the OECD to undertake a stock-take of existing data sources that currently inform countries’ social protection systems, reviewing the extent to which they generate data that can be disaggregated by gender, age, disability, and other relevant individual characteristics, and are underpinned by gender-sensitive survey methodology and tools.

- Undertake a cost-benefit analysis of shifting emphasis and standards in measurement systems to focus more strongly on individual-level measurement, including considering the benefits of improved disaggregation, visibility of vulnerable populations, and accuracy of inequality data.

G20 countries interested in progressing these priorities now could pursue the following steps:

- Increase resourcing for and regular production of gender statistics.

- Through national statistics offices, progress recognition of methodologies for individual-level, gender-sensitive data collection in the regional and global statistics bodies in which they participate.

- Integrate expectations regarding data that can support multiple level disaggregation into national data standards.

- Integrate commitments to gender-sensitive measurement of poverty and inequality and funding regular data collection in national strategies and policies, including development cooperation.

References

Shaida Badiee, Eric Swanson, Lorenz Noe, Tawheeda Wahabzada, Amelia Pittman and Deirdre Appel, State of Gender Data Financing 2021, Open Data Watch and Data2X, 2021 https://data2x.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/State-of-Gender-Data-Financing-2021_FINAL.pdf

Anna Tabitha Bonfert, Talip Kilic, Heather Moylan, and Miriam Muller, “Three ways to tackle gender data gaps – and 12 countries embracing the challenge”, in The World Bank Data Blog, 7 February 2022 https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/three-ways-tackle-gender-data-gaps-and-12-countries-embracing-challenge

Sylvia Chant (ed), International Handbook of Gender and Poverty: Concepts, Research, Policy, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2010

Catherine Cozzarelli and Susan A. Markham, “Capturing women’s multidimensional experiences of extreme poverty” in Rajiv Shah and Noam Unger (eds), Frontiers in Development 2014: Ending Extreme Poverty, US Agency for International Development, 2014 https://2012-2017.usaid.gov/frontiers/2014/publication/section-1-capturing-womens-multidimensional-experiences-extreme-poverty

Joanne Crawford, Kylie Fisk, Joanna Pradela, Carol McInerney, Cheryl Russell and Patrick Rehill, Guidance note: Equality Insights and individual-level, gender-sensitive measurement of multidimensional poverty and inequality, Melbourne, International Women’s Development Agency, 2021 https://equalityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EI-Guidance-note-web.pdf

Roberto Cuellar, Social Cohesion and Democracy, Stockholm, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2009 https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/the-role-of-the-european-union-in-democracy-building/eu-democracy-building-discussion-paper-27.pdf

Development Initiatives, Assessing Contributions of the Individual Deprivation Measure, 2020 https://equalityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Assessment-of-IDM-Contributions-FINAL-corrected.pd f

Development Initiatives, Assessing Costs of the Individual Deprivation Measure, 2020 https://equalityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Assessing-the-Costs-of-IDM-FINAL-corrected.pdf

Kylie Fisk, Carol McInerney, Patrick Rehill, Joanne Crawford and Joanna Pradela, Gender Insights in the Solomon Islands: Findings from a two-province study using the Individual Deprivation Measure, Melbourne, International Women’s Development Agency, 2020 https://equalityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Gender-insights-in-the-Solomon-Islands-Equality-Insights.pdf

Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, Making the case: More and better financing for development data , 2018 https://www.data4sdgs.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/Financing%20for%20Development%20Data%20Pamphlet%20FINAL_27Mar.pdf

Ravi Kanbur, “Globalization, Growth and Distribution: Framing the Questions” in Ravi Kanbur and Michael A. Spence (eds), Equity in a Globalizing World, Washington, The World Bank on behalf of the Commission on Growth and Development, 2010 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/2458/548910PUB0EPI11C10Dislosed061312010.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ravi Kanbur, Intra-Household Inequality and Overall Inequality, Cornell Dyson School Working Paper 20166-11 2016 http://publications.dyson.cornell.edu/research/researchpdf/wp/2016/Cornell-Dyson-wp1611.pdf

Fazley Elahi Mahmud and Joanne Sharpe, Social Protection’s contribution to Social Cohesion. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2021 https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/social-protections-contribution-to-social-cohesion.pdf

Melissa Meinhart and Cheryl Russell, Equality Insights Rapid: Tool Development Report, Melbourne, International Women’s Development Agency, 2022 https://equalityinsights.org/resources/equality-insights-rapid-tool-development-report/

Open Data Watch, Paris 21, Data2x, UN Women, “Solutions in Scarcity: Smart Financing for Gender Data: Introductory presentation”, Navigating the Landscaping of Gender Data Financing, 2022 Event Series https://opendatawatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/blogs/Solutions-in-Scarcity-SceneSetting.pdf

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Caregiving in crisis: Gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during COVID-19, Paris, OECD, December 2021, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/caregiving-in-crisis-gender-inequality-in-paid-and-unpaid-work-during-covid-19-3555d164/

Social Research Centre, Individual Deprivation Measure Within Unit Sampling Options: Indonesia and South Africa, Melbourne, 2020

United Nations Economic and Social Council, Statistical Commission, Report of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific on statistical development in Asia and the Pacific (E/CN.3/2019/7) 5-8 March 2019 https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/50th-session/documents/2019-7-ESCAP-E.pdf

United Nations, Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, 4-15 September 1995, (A/CONF.177/20/Rev.1) New York, United Nations, 1996 https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/Beijing%20full%20report%20E.pdf

United Nations Economic and Social Council, High Level Political Forum, Summary by the President of the Economic and Social Council of the high-level political forum on sustainable development convened under the auspices of the Council at its 2019 session (E/HLPF/2019/8), 9–18 July 2019 https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N19/251/18/PDF/N1925118.pdf?OpenElement

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Conference of European Statisticians, Expert meeting on measuring poverty and inequality: SDGs 1 and 10, Household-level measurement masks gender inequality across three dimensions of poverty, Working Paper 8, 5-6 December 2019 https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/ge.15/2019/mtg2/8._Intern_Women_DevAgency.pdf

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Conference of European Statisticians, Work Session on Gender Statistics, Measuring gender inequality within the household using the Individual Deprivation Measure in Fiji, Working Paper 24, 15-17 May 2019 https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/ge.30/2019/mtg1/WP24_Fisk_ENG.pdf.

United Nations Statistical Division, UN methodological guidelines on the production of statistics on asset ownership from a gender perspective, Studies in Methods Series F No. 119, New York, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019 https://unstats.un.org/edge/publications/docs/Guidelines_final.pdf

UN Women, Counted and Visible: Toolkit to Better Utilize Existing Data from Household Surveys to Generate Disaggregated Gender Statistics, Inter-Secretariat Working Group on Household Surveys, UN Women, 2021 https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/Toolkit/Counted_Visible_Toolkit_EN.pdf.

UN Women and Pacific Community, Pacific Roadmap on Gender Statistics, 2020 https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/Pacific-Roadmap-Gender-Statistics.pdf

US Agency for International Development, Vision for Ending Extreme Poverty, Washington, DC, USAID, 2015 https://2012-2017.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/Vision-XP_508c_1.21.16.pdf

Scott Wisor, Sharon Bessell, Fatima Castillo, Joanne Crawford, Kieran Donaghue, Janet Hunt, Alison Jaggar, Amy Liu and Thomas Pogge, Individual Deprivation Measure – a gender sensitive approach to poverty measurement, Melbourne, International Women’s Development Agency, 2014 https://www.individualdeprivationmeasure.org/resources/arc-report/

World Bank, Monitoring Global Poverty: Report of the Commission on Global Poverty. Washington, World Bank, 2017 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25141

World Economic Forum, The Global Risks Report 2022, 17th edition, World Economic Forum, 2022 https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2022.pdf

- Health (child mortality, nutrition), education (years of schooling, school attendance), and living standards (cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity, housing materials, assets). https://ophi.org.uk/multidimensional-poverty-index/ ↑

- Including Equality Insights, under the brand used in earlier phases of work, the Individual Deprivation Measure. ↑

- From August 2020, the International Women’s Development Agency (IWDA) has taken forward this work as a flagship program Equality Insights. ↑

- The initial research collaboration to develop a new measure was led by the Australian National University (ANU), with IWDA as the industry Linkage Partner, together with the Philippines Health and Social Science Association, University of Colorado at Boulder, and Oxfam Great Britain (Southern Africa), with additional support from Oxfam America and Oslo University. The research was funded by the Australian Research Council and partner organisations. ↑

- Fiji, Indonesia, the Philippines, Angola, Mozambique and Malawi. ↑

- Equality Insights has no upper age cut off for survey respondents. This contrasts with other multi-topic surveys such as the Demographic and Health Survey and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey that focus on women of reproductive age. While older women are recognised as a particularly vulnerable group, and experience high rates of poverty and homelessness in some countries, their circumstances are poorly captured in much routine data collection. ↑

- Drawing meaningful and statistically significant conclusions at multiple layers of disaggregation is conditional on sample size. ↑

- Targeting of policy and programming to address poverty and inequality is often informed by household-level measures of poverty such as a wealth index, with support directed to households in the bottom quintiles. Equality Insights has used the unique data set generated by sampling multiple individual adults in randomly selected household to examine how often wealthier households (not the focus of interventions) are home to individuals experiencing deprivation. We found that across nearly all 15 dimensions, a majority, and often a vast majority, of asset-wealthy households were home to at least one individual experiencing deprivation as measured by Equality Insights. Their experiences of poverty would be invisible in the data in the absence of an individual-level multidimensional method of poverty measurement. Recovery policies and programs that rely on household-level data will overlook these individuals. A combination of within-household sampling and individual-level measurement can help to ensure more inclusive social protection efforts that reach those who need it most. Independent evaluation assessed the within-household sampling used by Equality Insights as cost-effective, compared to simple random sampling of individuals (Development Initiatives 2020a). And while this method creates a degree of clustering in the data, it does not produce redundant information, as household members are sufficiently different from each other (Social Research Centre, 2020). ↑

- The report on development of Equality Insights Rapid (Meinhart and Russell 2022) describes considerations and rationale for the items included in the Equality Insights Rapid questionnaire and provides question wording for every module at the time of publication. Subsequent use in Tonga and the Solomon Islands has seen some minor changes in wording. An updated full survey form is not currently available online. ↑

- Six data sets were collected under a previous brand, the Individual Deprivation Measure, two using the new Equality Insights Rapid tool. ↑