Diversification is important because it is associated with economic growth and reduced volatility. Diversification of exports, which provide foreign exchange and enable imports of critical goods, services, and know-how, is crucial for developing countries. The question we address in this brief is how export diversification is affected by trade policies, including multilateral rules, regional trade agreements, and national measures. The record on diversification is poor across a large number of developing countries, especially in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. Asian and Eastern European countries have performed better. Though diversification first requires domestic reforms, the current trading system does not help. The world trading system does not support developing countries with export diversification; moreover, the situation is deteriorating. To promote export diversification in developing countries and to sustain long-term global growth, the Group of Twenty (G20) must restore the credibility of the rule-based system. Reducing tariffs and tariff escalation in labor-intensive manufactures is critical. In many developing countries, the diversification potential for agriculture is severely impeded by subsidies, tariff barriers, and protectionist standards. Individual countries can take many steps to foster export diversification, the most important of which are improving the efficiency of their service sector, liberalizing imports of services, and encouraging inward direct investment. Reforms of the world trading system, spearheaded by the G20, can help promote these changes at the country level.

Challenge

Export diversification is closely associated with rapid growth and improved stability in developing countries. Although policy makers usually think of export diversification as a shift from exporting agricultural products to exporting manufactured goods, we adopt a broader and more literal perspective—that is, diversification within sectors and across sectors. In other words, we are also interested in diversification within agriculture and toward agriculture, and within services and toward services. Cadot, Carrère, and Strauss-Kahn (2011) developed a useful decomposition of the widely used Theil diversification index.[1] They distinguish between diversification at the intensive margin (a more balanced export basket within existing products and markets) and diversification at the extensive margin (exports of new products or to new markets). Recent research has added a new dimension to measuring diversification, namely, quality upgradation, which is reflected in higher unit values for exports (IMF 2014). Our interest in these different facets of diversification reflects the fact that economic growth occurs across all sectors of the economy, and can take the form of improved quality as well as increased quantity.[2] The broader this growth process, the quicker and more sustainable the growth is likely to be.

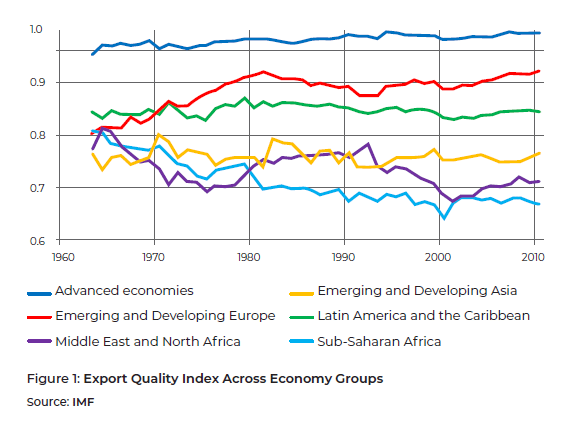

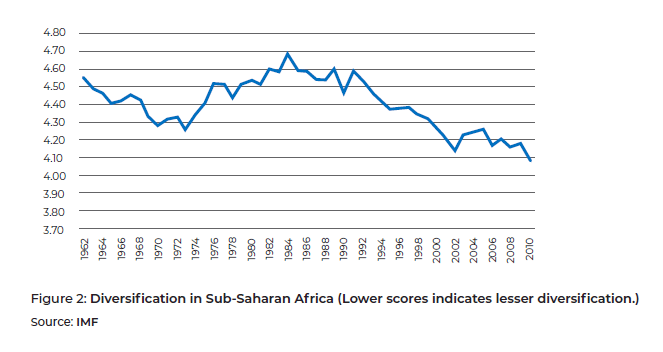

An examination of various indicators shows that in recent years export diversification and quality upgradation have shown little progress, and have even declined in most countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America (see figures 1 and 2). Many countries in Asia and Eastern Europe have done much better. Eastern European countries derived great benefits from their proximity to the European Union (EU), large amounts of investment/aid from their Western European neighbors, accession of several countries to the single market, and the far-ranging domestic reforms on which their accession was conditional. Asian developing countries benefited from very high rates of domestic savings and investment, a strong export orientation, increased intra-regional integration, and proximity to the Chinese growth pole. During periods of increasing diversification, such as the years preceding the financial crisis, diversification in the lagging regions occurred primarily at the intensive “geographic” margin, reflecting growth of exports from China and other Asian and European developing economies that enacted far-reaching market reforms in the 1990s and 2000s. The performance on the extensive margin, based on new products and quality upgradation, was weak even then—a sign that diversification did not reflect a profound structural transformation of those economies. These trends and those discussed below are illustrated in greater detail in a longer companion paper (Ait Ali et al. 2020).

The failure of many developing nations to diversify sustainably reflects institutional weaknesses and inadequate policy reforms at home. It is easily shown, however, that the trading system—as embodied in WTO disciplines and various bilateral and regional agreements—is not supportive of diversification. This is not to suggest that a rule-based system is intrinsically harmful to the prospect of diversification; on the contrary, it is essential. However, despite the great progress in making trade more open and predictable since 1945, major distortions remain; furthermore, over the last three years, the trend has been toward more impediments to diversification, not less.

These impediments are observed in all four main sources of export revenue for developing countries: mining and minerals, agriculture, manufactures, and services. Today’s advanced countries diversified initially from agriculture to manufacturing, but this traditional path is far less prevalent today.

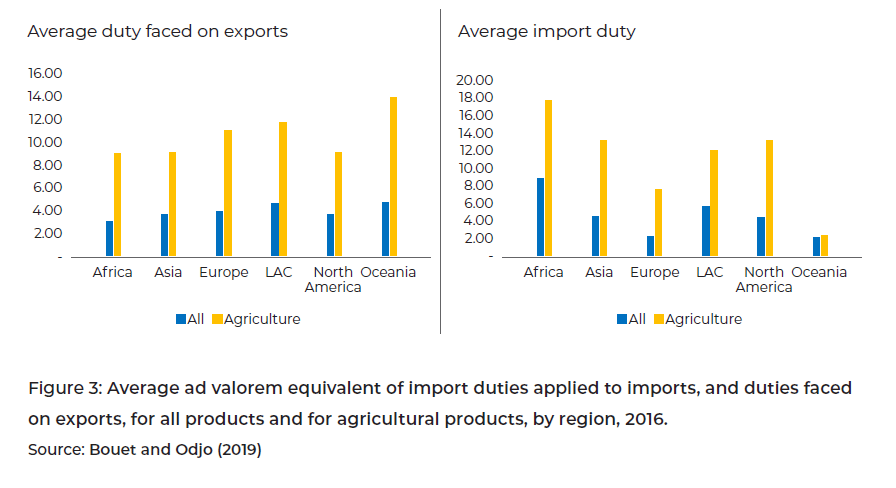

In agriculture, productivity improvements through engaging in the world market are impeded by extensive protection in both advanced and developing countries. Such protection takes the form of high tariffs, tariff peaks, tariff-rate quotas, sanitary and phytosanitary standards[3] that many poor countries cannot meet, and large scale subsidization (see figure 3).

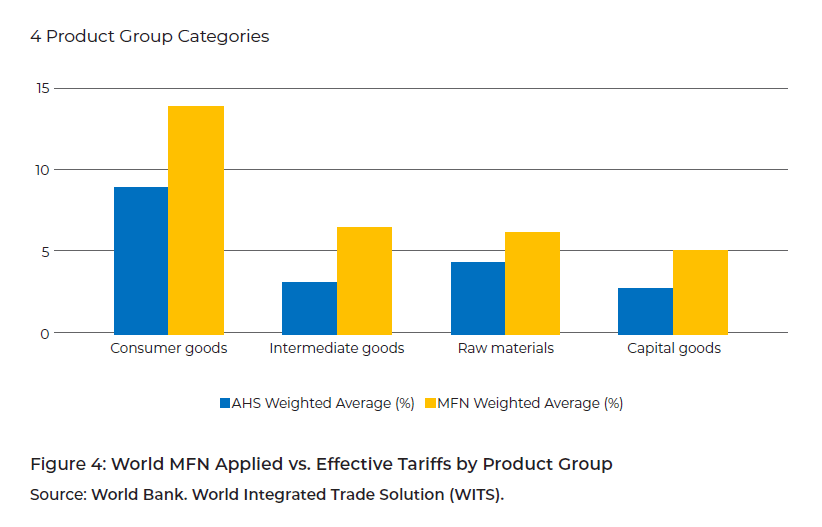

Trade of manufactures has become far more open. However, only a few developing countries have been able to take advantage of this openness, and a dramatic escalation of international competition occurred after the entry of China and other Asian and East European exporters into the global trading system. The trade barriers that remain are especially damaging to the prospects of the poorest countries. These include high tariffs and tariff peaks in the most labor-intensive manufactures, increasing technical standards, and hidden industrial subsidies. Another barrier is the protection of intellectual property, beyond what may be reasonably required to promote innovation, through very long patent lives and, in some instances, the fear of meritless litigation. Importantly, tariff escalation provides incumbents with far higher effective protection than is generally understood, with Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariffs highest on final products (see figure 4). Discretionary preference schemes that are unevenly applied and require onerous certification involving rules of origin provide only limited relief from these barriers. Meanwhile, because of automation, manufacturing creates far fewer jobs than in the past.

Policy barriers to trade in services are mainly regulatory in nature and tend to be more complex than barriers to trade in goods. Although there has been progress in services trade liberalization over the years, certain sectors such as professional services remain characterized by high levels of protection, even in OECD countries. Restrictions on foreign entry, movement of people, and competition, as well as regulatory complexity, are the main barriers to trade in services. Their impact varies across sectors, but typically these barriers are quite significant with respect to transport and professional services. Restrictions on foreign entry are pervasive in transport sectors and in broadcasting and telecommunications, motivated by national security considerations. Restrictions on the movement of people, in turn, are significant for legal and accounting services as well as for infrastructure services such as construction, engineering, and architecture. Recent policy changes have generally increased the level of trade restrictions across most service sectors, affecting not only foreign establishment, movement of people, and modes of trade delivery but also the remote provision of services (e.g. through the Internet), as barriers to computer and audio-visual services have also increased.[4]

Although tariff and non-tariff barriers on imported raw materials tend to be lower than those on final and intermediate products, various restrictions on trade in mining and mineral products, including export taxes, are disruptive to global supply chains and impede countries’ ability to diversify their economies in various ways. Import tariffs and export taxes are treated differently under WTO law. In the wake of several rounds of GATT/WTO negotiations, applied import tariffs have been cut, and ceilings have been agreed upon in many instances (Korinek 2019). However, export taxes are not subject to such limitations and are levied for many reasons, ranging from revenue-containing prices for domestic consumers to countering tariff escalation with trading partners. According to the World Bank, 55 countries impose 277 non-tariff measures on exports, including on metals and minerals. Currently, rigorous restrictions on exports of medical goods are impeding many countries, especially ill-equipped developing countries, from dealing effectively with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows are generally more stable and sustainable over the long term than portfolio capital flows because of the nature of greenfield investment decisions and decisions relating to acquisition of an ownership stake, which are difficult to reverse. The growth effects of foreign investment result mostly from knowledge brought into the host country by the investing entity.[5] Therefore, FDI is key for diversifying the economies of countries at all levels of development. In manufacturing, foreign investment is paramount for inclusion in global value chains, which also allow for specialization in services. Current investment provisions in international law are weak. Foreign investments have limited coverage under WTO rules, and only some provisions under the General Agreement in Trade in Services (GATS). Bilateral investment treaties form the backbone of international investment rules. While these treaties

have increased FDI between signatories by providing greater investment protection, mostly through Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms, few include provisions to increase access for foreign investors. Moreover, the ISDS remains controversial on account of concerns that it can reduce the receiving country’s ability to enact laws and regulations, and other policy reforms.

Since diversification often entails the exploitation of specific niches in the product spectrum, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can often play a crucial role in diversification. However, their small size often impedes them disproportionately as they try to internationalize their activity.

Proposal

Export diversification helps promote economic growth and stability in developing nations. These nations account for a large and growing share of global economic activity, but the world trading system exhibits, besides numerous and significant benefits, numerous barriers to diversification; furthermore, these barriers are also rising. What can be done to address this? We distinguish between steps that need to be taken at the level of the G20 and those that individual countries can take on their own.

G20 trade policy and the WTO

A rule-based global trading system assures predictability and openness and is essential to promote export diversification. The present system is far from perfect, but it is anchored in non-discrimination principles and binding market access commitments; furthermore, it is complemented by an effective dispute settlement mechanism to secure enforcement. The WTO, and before it, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, have provided a solid foundation for rapid economic growth. Yet the system suffers from long-standing pockets of entrenched protectionism in trade in goods— particularly in agriculture—as well as from high barriers to trade in services that limit countries’ diversification potential.

In recent years, the trade policy landscape has deteriorated rapidly and alarmingly. Managed trade is gaining traction, rules are becoming increasingly fragmented among competing spheres of influence, and global trade governance is weakening. In addition, the system needs to catch up with economic and technological transformations, discipline other distortions, and move toward more inclusive and sustainable outcomes (Tan and González 2020).

If countries are to have the opportunity to diversify their exports as a means to grow and to reduce volatility, it is necessary to revitalize global trade rule-making through international cooperation. Cooperation is also required to further secure open markets, not only in advanced economies, but also in emerging markets—these markets are critical for geographic diversification and yet tend to maintain high trade barriers. Priority areas for collective action, if not among all then among the willing, include:

- Reducing and eliminating tariff escalation, tariff peaks, and high tariffs that constrain value addition in both agriculture and manufacturing, particularly in potential export products of developing countries.

- Strengthening and updating rules to tackle trade-distorting subsidies. In the case of agriculture, domestic support measures that negatively impact production and trade, with high concentrations in specific commodities, should be significantly reduced; in the case of manufactures, there is a compelling case to clarify and agree on new rules, particularly to govern provision of subsidies by state-owned enterprises in non-market economies.

- Limiting export restrictions and export taxes on natural resources to avoid disruption of global supply chains.

- Leveraging the GATS platform to reignite a round of services trade liberalization, as it relates to cross-border trade or FDI, and concluding the ongoing negotiations on disciplines for domestic regulations.

- Adopting a set of rules for investment facilitation to streamline investments, foster transparency, and improve implementation of domestic regulations.

- Agreeing on a framework to govern digital commerce to reduce transaction costs and create new opportunities and sources of value addition.

- Supporting the improved participation of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in international trade through a set of horizontal and non-discriminatory solutions that avoid subsidies and preferences, which distort competition. Aid programs— through bilateral agencies or the International Financial Corporation—can promote the establishment of SME support centers, export promotion programs, or Aid for Trade programs that target the opportunities open to SMEs. Key areas in which SMEs need support are market intelligence, regulatory information, and financing.

Additionally, resolving the crisis of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism is critical not only for conflict adjudication, but also because the crisis may reduce the ability of WTO members to engage in further rulemaking to support diversification.

National trade policies

Although international economic cooperation is needed to adopt new trade rules and improve access to foreign markets, countries can also adopt unilateral measures to improve their own export competitiveness and realize their diversification potential.

A national action plan for trade diversification could include the following measures:

- Reducing or eliminating tariffs on raw materials, inputs, and capital equipment to facilitate integration into global and regional value chains and to foster technology transfer.

- Revisiting non-tariff barriers, particularly to align standards with export markets, and thereby reduce the time and cost of compliance, and support quality infrastructure.

- Reducing high costs of export and import by streamlining both border and documentary compliance, and reducing restrictions to trade in services, which may hinder logistics performance, transport connectivity, and distribution services.

- Liberalizing trade in services and adopting an appropriate regulatory framework to foster competition in energy, telecommunications (acknowledging national security concerns), financial services, and professional services that are a source of competitiveness for downstream products and services.

- Implementing an investment-friendly regime to facilitate, attract, retain, and expand FDI, particularly in non-traditional sectors that contribute to trade diversification and integration into supply chains.

- Adopting a legal framework conducive to digital trade, including provisions to guarantee free data flows and safeguard privacy and security, among other concerns.

- Supporting the integration of SMEs in international trade through appropriate trade, finance, and export promotion measures.

The measures outlined above require G20 leadership, with close collaboration between members from both developing and advanced countries, as well as concerted policy reforms at both the multilateral and national levels. The benefits that would accrue from the export diversification and growth acceleration of lower-income countries, which are home to a large share of humanity and nearly all of the world’s absolute poor, are difficult to overstate.

Acknowledgment

Uri Dadush, Lead author. Sait Akman and two anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments. Mahmoud Arbouch and Alexander Cullen provided excellent research assistance. This brief is based on a longer paper by the authors (Ait Ali et al., 2020)

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Ait Ali, Abdelaaziz, Mohammed Al. Doghan, Muhammad Bhatti, Carlos Braga, Uri Dadush, Abdulelah Darandary, Anabel González, and Niclas Poitiers. “Diversification and the World Trading System.” Manuscript Submitted to the T-20 Secretariat, April 2020.

Borensztein, Eduardo, Jose, De Gregorio, and Jong-wha, Lee. 1994. “How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth?” Journal of International Economics 45

(1): 115–135. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0.

Bouet, Antoine, and Sunday P. Odjo, eds. 2019. Africa Agriculture Trade Monitor. IFPRI. http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/133395/filename/133601.pdf.

Cadot, Olivier, Carrère Carrère, and Vanessa Strauss-Kahn. 2011. “Export Diversification: What’s behind the Hump?” Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (2): 590–605.doi:10.1162/REST_a_00078.

International Monetary Fund. 2014. “Sustaining Long-Run Growth and Macroeconomic Stability in LowIncome Countries – The Role of Structural Transformation and Diversification.” Last Modified March 05, 2014. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/030514.pdf.

Korinek, Jane. 2019. “Trade restrictions on minerals and metals,” Mineral Economics, Springer & Raw Materials Group (RMG), Luleå University of Technology 32, no. 2 (July): 171–185.

OECD. 2020. OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy trends up to 2020. Paris: OECD.

Tan, Yeling and Anabel, González. 2020. “The Future of Trade and Investment: A Call to Prevent Economic Fragmentation.” World Economic Forum. Last Modified January 2020. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GFC_Trade_Briefing_Paper.pdf.

World Bank. “World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS) Database.” https://wits.worldbank.org.

Appendix

[1] . We employ The Theil index as it is used most widely, although it has shortcomings as any index does. The index is complemented by the IMF index of export quality to provide a more complete picture of evolving export structures, including the extent to which countries are moving up the value-added chain (see figure 1). The data presented in this brief draw mainly from published computations by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), using the latest available years.

[2] . Import diversification is also very important in promoting growth and diversification of exports. The recommendations section refers to the need for a liberal import regime, especially in intermediates.

[3] . It should be recognized, however, that legitimate sanitary and phytosanitary standards can provide important discipline to improve quality and safety in countries across the development spectrum.

[4] . See OECD (2020).

[5] . For a discussion on the growth effects of FDI, see Borensztein et al. (1995).