To achieve the G20 member nation’s objective, both individually and collectively, of achieving growth that is strong, sustainable, balanced, and inclusive, it is critical to enact policies and design programs that target and empower the large population of rural women. Promoting rural women’s economic empowerment presents unique challenges that require multidimensional approaches to overcome. Evidence shows that narrow solutions, such as focusing on finance alone, are rarely effective (World Bank 2017). Empowering rural women economically will require at least as much investment in capacity building, institutions, and cultural change as much as in access to finance and markets.

Challenge

By 2030, about 1.6 billion people will reach working age in low and middle-income countries—the number is lower in high income countries, but the need to stimulate job creation is just as urgent (World Bank, 2017). Fifty percent of the world’s population is and will be female, but women currently comprise only about 39 percent of the labor force globally (WDI 2018). Economies that discriminate against women—in entrepreneurship and labor force participation—undermine their own growth trajectory. According to some research, gender gaps cause an average income loss of 15% in OECD economies and losses are estimated higher in developing economies (WBG 2018).

The challenge to creating jobs for women in rural areas is even more difficult, but no less important. For this brief, rural refers to areas that are remote, less densely populated, have fewer and/or more expensive services given high transaction costs, and have a higher proportion of economic activity derived from the natural resource bases. In some cultures, given their remoteness, rural communities can be more culturally conservative, adhering to traditional views and roles.

A paucity of disaggregated data limits the ability to paint a data story on the empowerment of rural women, but there have been sufficient studies to frame the nature of the challenge that policies and programs must overcome.

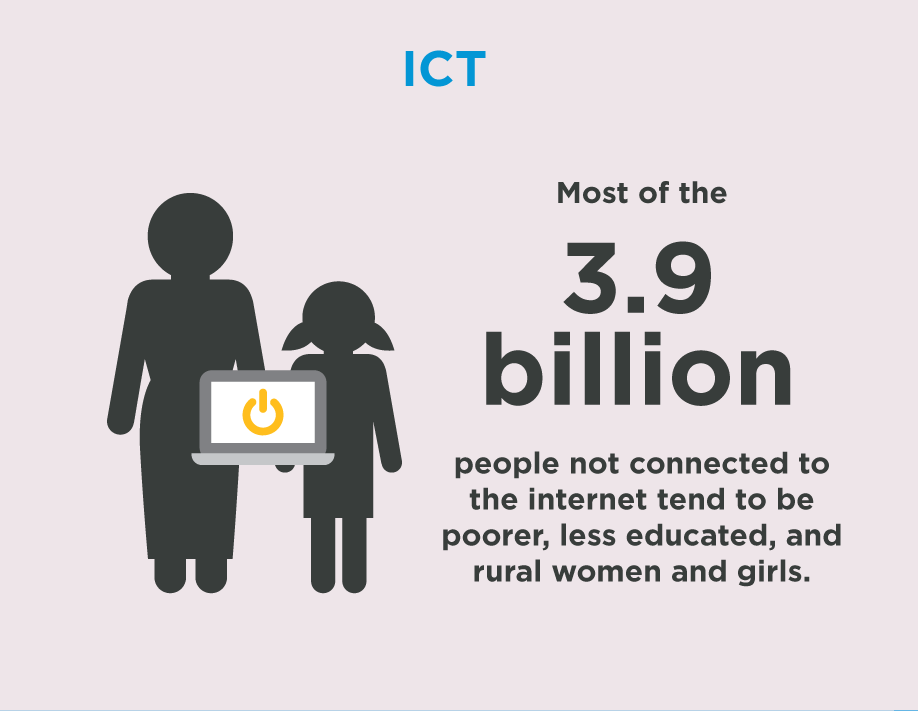

- Over half of all poor rural women lack basic literacy (UN Women, 2018). The same is true for numeracy, and both prevent women from managing money, engaging in trade, and accessing information. This has implications for ICT based solutions for women’s empowerment in rural areas (May, 2015). It also often condemns women to low-skilled, low wage employment—often in the informal sector.

- Most of the 3.9 billion people not connected to the internet tend to be poorer, less educated, and rural women and girls (UN Women, 2018).

- A rural girl is twice as likely to be a child bride in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, and South Asia has the most child marriages in the world (Girls Not Brides, 2018). Early marriage ends a girl’s education, moving her into household and reproductive work at the expense of their economic empowerment.

- Time poverty impacts rural women more than men, and in many countries, more than urban women. Rural women perform care work—cleaning, cooking, child and elder care, and community obligations—in disproportionate amounts, limiting their ability to engage in economic activity, attend training, and travel distances to banks or markets.

- Often, women’s legal rights are not either not protected by the law or are constrained by the law—e.g., out of 189 countries over 30% legally restrict women’s agency and freedom of movement in at least one area (World Bank Group, 2018).

- Even where the legal framework empowers women, cultural norms can present obstacles contrary to the law—e.g., a women’s livestock cooperative in India was prevented from registering because they had not male members even though the law did not have such membership requirements.

This note is organized around the framework endorsed by the UNSG’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment, which categorizes women’s economic activity into the formal economy, women owned enterprises, agriculture, and the informal economy. Within those four employment areas, the note explores several of the seven areas for reform to identify the policies and actions that the G20 member nations can take within their own economies and in their support to other economies.

Proposal

When women earn their own income, their control over that income can increase, and they are more likely to re-invest in their household—children’s education and health, better food and nutrition for the family, increasing livelihood assets for the family. This can contribute to a virtuous inter-generational cycle that can raise a family out of poverty over time. Any economic growth plan must include elements that create economic opportunities for women in rural areas—through a combination of job creation and investment in education and training to ready women for the job opportunities of the future.

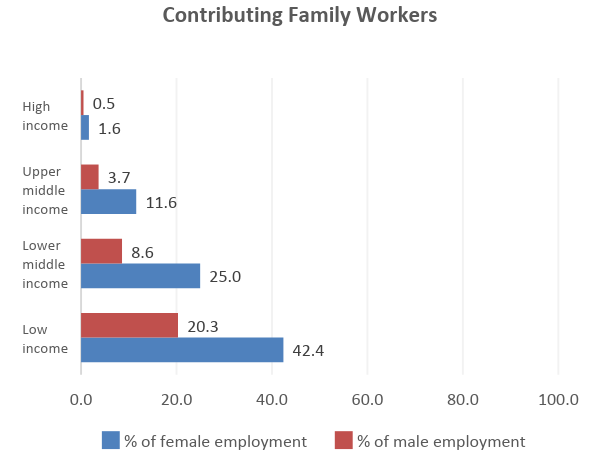

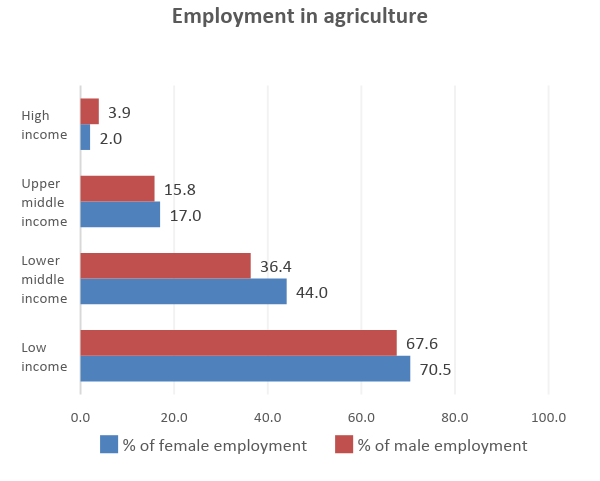

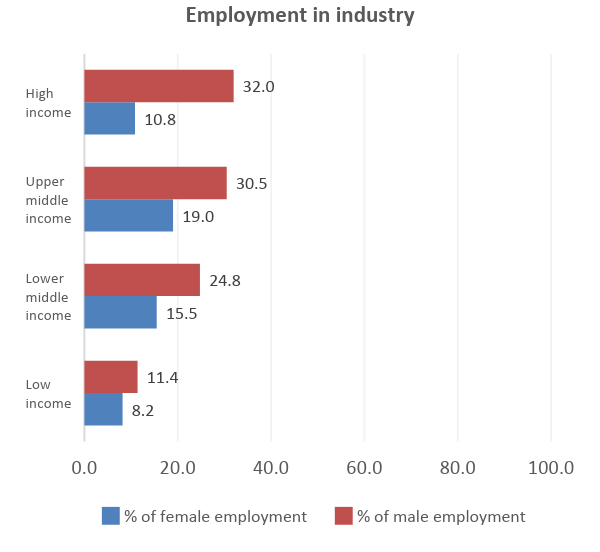

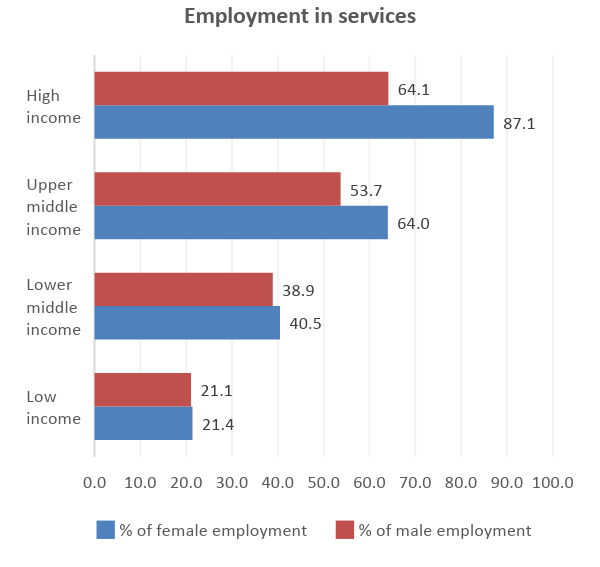

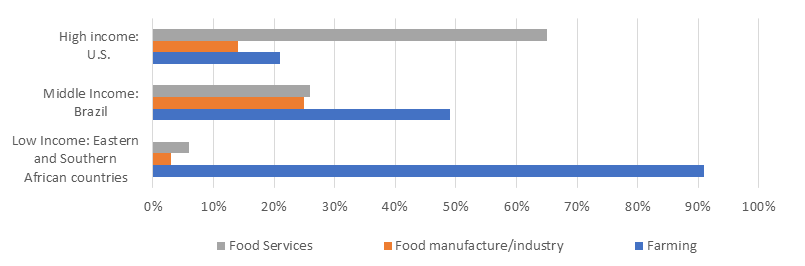

Job opportunities vary across income groups (see figure 1) as do the constraints to women’s work. In low-income economies (LIEs), agriculture and natural resources is the dominant job sector, employing 71 percent of working women. Women also disproportionately work as contributing family labor (often unpaid). As economies move from low-income to high income, the structure of the workforce changes. In lower middle-income economies (LMIs), agriculture and natural resources still employs 44 percent of working women, but 41 percent of women work in the service sector jobs and 15 percent work in industry—one can assume these are largely paid jobs or self-employment because only 1.4 percent of women are employers. In upper-middle income economics (UMIs), there is a clear shift to service sector jobs (64 percent), followed by industry (19 percent) and then agriculture (17 percent). While agriculture is the smallest sector in high-income economies (HIEs), those are the only countries where slightly more men than women work in the sector (3.9 percent compared to 2 percent for women).

Figure 1 Male and Female Employment in Sectors by Country Income Group, 2017

Source: World Development Indicators compiled from International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT database. Data retrieved in November 2017.

The UNSG’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment, categorizes the forms that women’s economic activity takes into four broad and overlapping areas:

- The formal economy—salaried positions and self-employment that is regulated by labor laws and covered by some form of social security. Paid work can be in low, medium, and high-skilled jobs across all sectors (agriculture, industry, services). Rural women with formal sector jobs face unequal pay and sexual harassment—as with their urban counterparts—but they also face limited job opportunities due to remoteness—companies are not attracted to rural areas due to infrastructure shortfalls and a mismatch of skills needed by the workforce. Many of the challenges to self-employment and entrepreneurship among rural women are shared across income groups—such as, access to sufficient finance including working capital, which impacts access to assets; access to information and mentoring to grow a business; access to markets is often informal, with low economic returns, and reliance on family money or MFIs for financial capital. Even when training is available, it may not be feasible due to accessibility and the volume of unpaid informal work rural women do. Where broad-band is available and general education levels are higher, there is a lack of distance learning available. Training is not adapting as fast as the market is changing. There needs to be greater focus on diversification, environmentally friendly production, entrepreneurship, financial planning and new communication technologies, this will allow women to move out of traditionally feminized sectors and improve their earning potential.

- Women-owned enterprises—companies that are majority owned (51%+) and controlled by women. Most women-owned enterprises are concentrated in the informal sector and are “micro-size, low productivity and low-return activities (ILO 2010).” An estimated 70 percent of women-owned SMEs in the formal sector in emerging markets are underserved by financial institutions (World Bank, 2015), amounting to a financing gap of $285 billion (Global Markets Institute, 2014). The challenge for rural women is lack of access to formal finance due to distance, lack of collateral, and societal norms, lack of literacy and numeracy, etc. In LIEs and LMIs, rural women are more likely to run very small (5-9 staff) and micro enterprises (<5) that are often informal and therefore difficult to finance and often less competitive in the marketplace.

- Agricultural and natural resource based work. According to (UN Women, 2018), agriculture still provides the most jobs for rural women, especially in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa where the rural populations are still in the majority and 60 percent of women work in agriculture (World Bank Group, 2017). East Asia and the Pacific and North Africa have 30%, the Arab States 20%, and there are fewer in the urbanizing regions of Latin America, Eastern Europe, Europe, and North America. Jobs are not just in crop agriculture, but also in livestock rearing, fishing and aquaculture, and harvesting of forest products. Current trends in migration are greatly impacting the nature of work by women in rural areas, particularly in agriculture (see box).

Box 2 Rural out-migration: a view from two angles

| Between 1990 and 2015, the share of migrating men increased 10 percent while the share of women declined by 13 percent. However, much work remains to understand the motivations of women labor migrants. Women migrants are usually considered to be companions of male migrants, domestic workers, or victims of trafficking (Joseph and Narendran, 2013). In South Asia, which made up almost 15 percent of global migrants in 2015, with different patterns between men—more distant and permanent and based on a contractual agreement—and women—more seasonal and neighbourhood or culturally contiguous in nature (Khatri, 2010; Dohrethy, et al., 2014; and Beneria et al., 2012). Women’s migration decisions are also heavily influenced by cultural norms limiting mobility and agency. Migration from South Asian countries like Bangladesh, India, and Nepal are driven by the economic conditions at the destination countries, but the policies related to migration do not recognize the particular drivers and risks faced by women. Gender sensitive policies need to be defined at the global and regional level that would bind governments committed to women’s mobility and vulnerability. Given that male out-migration from rural areas is higher than that of females, this implies that more women are left behind as de jure head of household. The forthcoming study, Male Out-migration and Women’s Work and Empowerment in Agriculture: The Case of Nepal and Senegal seeks to describe the impact of migration on women’s work and empowerment. Using tools like the Additional Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (A-WEAI), the study finds that male out-migration is strongly and significantly linked to significant changes in the types of work and responsibilities of women who stay behind. In both countries, women reduce work as contributing family members and increase participation in other income-generating activities. In Nepal, women in households with international migrants continue to farm but in different roles – as employers or self-employed workers. In Senegal, women shift from contributing family labor to trading or other non-agricultural self-employment or wage work. Policies and programs for rural economic development must recognize the impact of male outmigration—quantifying the number of de facto women acting as head of household, for example—and providing training, credit, and mentoring services for women to either stay in agriculture competitively or to move out of agriculture and into gainful self-employment. Sources: Gender migration patterns: Iyer, Sandhya and Ananya Chakrabarty (2017), ‘Gendering the Gravity Model of Migration in South Asian Context: Evidence of Capabilities-Growth Nexus’, paper at the WIDER Development Conference, Migration and mobility, held on 5-6 October 2017 in Accra, Ghana. Male out-migration study: personal communication (5/7/2018) with Anuja Kar, Economist and project manager, Global Food and Agriculture Practice, World Bank |

- The informal economy—workers and enterprises not regulated or protected by the state. Nearly 40 percent of female wage workers do not contribute to any form of social security (ILO, 2016). In Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and South Asia, women not working in agriculture usually have informal non-farm employment (day labor, producing artisan goods, etc.). According to one source, the size of the informal sector as a percent of official GNI was 40 percent in developing countries, 38 percent in “transition countries”, which can serve as a proxy for LMIs and UMIs), and 18 percent in OECD countries (Schneider, 2002). In South Asia, almost 80 percent of women work in the informal non-agriculture sector. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have the most women working as contributing family workers—35 percent and 32 percent, respectively—or as own-account workers—43 percent and 48 percent, respectively— (ILO 2016).

In contrast to their counterparts in urban areas, rural women—particularly those in LIEs and LMIs—are more likely to find employment and operate enterprises linked to the natural resource base. In HIEs and UMIs, the situation (as shown above) differs greatly from lower income economies with most women employed as wage and salaried workers—often in industry and services. Across all economies, women’s entrepreneurship is greatly constrained, with very small numbers of women employing others. This note will seek to differentiate between the needs of and potential solutions for rural women in different economies; however, four areas of economic activity could offer significant opportunities both in jobs and enterprise development.

The Green Economy. Definitions vary but green jobs are generally those occupations that help countries move toward a less carbon-intensive economy and adapt to the impacts of climate change. They include employment in such industries as renewable energy, energy efficiency, and other services contributing to climate mitigation, as well as those contributing to adaptation and climate resilience. Opportunities in the green economy can increase economic possibilities for women, particularly in newer industries such as, renewable energy. ILO estimates that by about 2030, between 15 and 60 million jobs could be created in the green economy (ILO 2012). Investing in training could enhance women’s entrepreneurship and job readiness in this sector and achieve the triple win of economic growth, ecological sustainability, and women’s empowerment. Although often described only in terms of their climate vulnerability, women are change agents and environmental managers-through their involvement in agriculture, animal husbandry, and forestry at levels from local to national-who can influence the development and deployment of sustainable solutions.

The Blue Economy. World Bank Group defines the blue economy as “comprising the range of economic sectors and related policies that together determine whether the use of oceanic resources is sustainable.” It seeks to “promote economic growth, social inclusion, and the preservation or improvement of livelihoods while ensuring environmental sustainability of the oceans and coastal areas”. Job opportunities cross primary production, services, and industry and include traditional ocean industries such as fisheries, tourism, and maritime transport, but also new activities, such as offshore renewable energy, aquaculture, seabed extractive activities, and marine biotechnology and bioprospecting. Women’s contributions to the blue economy have not received much attention because their participation is mostly limited to traditional, low value addition activities involving low skill-sets. These jobs are often informal and gender discrimination in terms of wages and work conditions is pervasive. The challenge is how states can translate the ‘blue economy’ into sustainable and equitable gendered distribution of opportunities. Currently, 98% of maritime employees are males (ITF 2015; UNECA, no date). Moreover, women are also the lowest paid in the industry (W20 208; UNECA, no date), while they produce (50%) of food globally (W20 2018) and contribute to mitigate climate change. This is a sobering fact if we consider that the blue economy provides a turnover of about US$3 and 6 trillion, and about 260 million jobs in the fisheries and aquaculture segments in the Indian Ocean alone (IORA 2018).

The Food Economy. Most data on agriculture employment refer to primary production—in crops, livestock, and fisheries. While these jobs decline as the size of the sector shrinks relative to industry and services, there is significant job potential in the broader food sector. According to the World Bank Group, “the food system extends moves beyond farm primary production to include activities along value chains, —such as food processing, packaging, regulations/safety standards, transportation, retailing, restaurants, and other services, etc. As incomes rise in a country, jobs tend to shift from primary production to off-farm jobs the food system. In fact, as figure 2 shows, more food system jobs in UMIs and HIEs fall into the industry and services sectors—providing (largely) formal sector paid jobs and own-account work.

Figure 2 Composition of Jobs in the Food Economy Across Income Groups

Rural/eco-tourism. Tourism is major engine for job creation and employment in rural areas. For example, eco-tourism can be a powerful tool to not only reduce poverty, but promote local participation, natural conservation and sustainable development. According to the ILO (2016), tourism directly created more than 107 million in 2015 (3% of the total employment) and it is expected to increase to 136 million by 2026. Eco-tourism in some countries, like Tanzania, contribute to 17% of the GDP annually (Mwesigwa & Mubangizi, 2016). Women’s role in eco-tourism has increased, as they tend to be linked to the protection of the environment and natural resources. Moreover, women participation in eco-tourism not only entails financial gains but a stronger link to the community and the place they live. A 5-year project led by the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) sought to transform the conditions of the tourism market into development opportunities for the rural communities of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador by promoting community-tourism entrepreneurships. As a result, 55% of tourism enterprises were led by women, facilitating their incorporation to the local market, as entrepreneurs. The project also helped increase rural women´s financial autonomy and the valuation for their work, contributing to empower women within the family and community. In addition, positive impacts extended to the schooling of children, their nutrition and, therefore, their future development (CAF, 2016).

| Figure 1 UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment, 2016 |

|

There are many potential job opportunities among the productive sectors across the economy. In LIEs and LMIs, especially, women are largely confined to the low-level, often informal, jobs that have lower remuneration than men. In There are several constraining factors—identified by the UNSG’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment that impact women’s economic opportunities. The next section describes how policy and programmatic initiative can shape a system that empowers women as agents.

The policy narrative on gender and development has the potential to shape women as passive recipients of development rather than active agents in advancing their own development through the opportunities presented by the economy.

Tackling adverse norms and Reforming Discriminatory Laws and Regulations

Recommendation: Every G20 member should commit to eliminating gender discriminatory laws from their systems by 2025. Further, G20 development donors should require reform in the legal framework governing women’s economic participation as a condition of official development assistance.

The World Bank Group’s Women, Business and the Law (WBL) program tracks the legal environment that either supports or prevents women’s economic empowerment. In its 2018 edition, WBL tracked 7 indicator sets across 189 countries. It found that one-third of the surveyed economies have at least one legal constraint for women to access institutions. About 40 percent of the economies have at least one constraint on women’s property rights.

The World Bank Group’s Women, Business, and the Law is a biennial survey to track how the policy and regulatory environment within economies supports or constrains women’s empowerment. It provides sourced data across 7 empowerment areas that countries can use to develop an action plan for women’s empowerment: accessing institutions, using property, going to court, providing incentives to work, building credit, getting a job, and protecting women from violence.

Table 1 Having the laws is not enough

| The importance of women’s empowerment for sustainable development is well known within policy making circles. Yet, it is too narrowly interpreted, focusing on the symptoms as opposed to the root causes of gendered patterns of inequality (True, 2003; Esquival, 2016) which are power dynamics, culture that perpetrates a patriarchal society, and lack of gender mainstreaming within relevant institutional and legislative frameworks. Underlying (and sometimes undercutting) the legal and regulatory environment are the cultural norms that define traditional gender roles—too often to the detriment of women. Countries cannot ignore the presence of discriminatory and patriarchal institutional frameworks that persist. Economic exclusion, marginalization, and violence and gender discrimination based on patriarchy and cultural structures persist for many women, but most notably for poor, rural women in the developing world (Jones and Perry, 2003). This is one of the most influential issues impacting women’s economic empowerment, but it is also the most difficult to reform as it requires long-term cultural change. In addition to reforming legal frameworks, countries must proactively educate citizens—especially women —about their constitutional rights (as well as their rights under cultural and personal law codes). Training for law enforcement officials on the rights of women they should protect and how to provide that protection is another strategy for supporting cultural change. Finally, engaging both men and women (and boys and girls) about the rights, privileges, and responsibilities they have under the law, it an important step. |

Recognizing, Reducing, And Redistributing Unpaid Work And Care

|

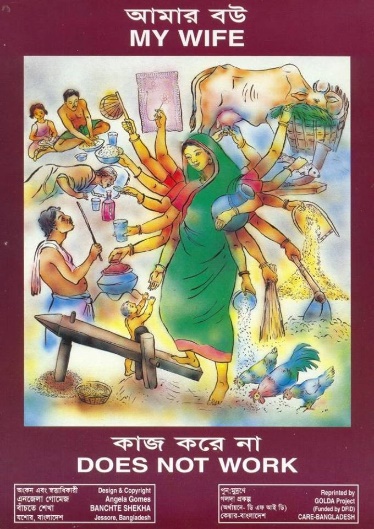

| A poster created by Banchte Shekha, an NGO in Bangladesh, encapsulates the unaccounted work of rural women and the societal attitudes toward them. |

Recommendation: Every G20 member nation commits to address the data deficit related to women’s unpaid work and lead the international community to work with the United Nations to update the System of National Accounts to better capture women’s unpaid work.

Women are, perhaps, the last generalists in an ever-specializing world. In addition to “economic work” (which is often categorized as chores), women spend a disproportionate amount of time on care of children and elders, cooking, cleaning, accessing water, etc. A 2015 study by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) for Manusher Jonno Foundation in Bangladesh tried to quantify the value of women’s unpaid work. According to the study, showed that the replacement value of women’s unpaid care work amounted to between 77 to 87 percent of 2014/15 GDP (CPD, 2015).[1] It also called for reform of the System of National Accounts, the standardized format created by the United Nations, treats women’s contribution to the economy. This is particularly relevant for LIEs and LMIs, where rural households operate family enterprises (farming, livestock, fisheries, artisan production, etc.), but usually only the male head of household is reflected as the economic actor.

According to Women Business and the Law (2018), of 189 countries reviewed, 55 do not provide for the valuation of nonmonetary contributions in a marriage. Even where countries do, this applies large to family law and dissolution of marriage and the shared access to safety net programs (like social security

in the United States). Still, in most countries, the assumption is that women not in the formal workforce are not making an economic contribution, leading to the assertion “my wife does not work”.

Figure 1 Does the law provide for the valuation of nonmonetary contributions?

Recommendation: Every G20 member nation should commit to supporting more and better child care to support working families, especially in rural areas. Through ODA, G20 nations can support provision of child services and the enactment of laws to provide child care in developing economies.

Child care is a key obstacle for women joining the workforce or even accessing training to build marketable skills. One of the biggest obstacles to women joining the labor force or expanding their business is the time demands from care work—the cooking, cleaning, child care, elder care, productive labor, and other duties that fall disproportionately on women than men.

There are many ways to support rural women’s economic empowerment: childcare subsidies, summer camps, flexible hours for working parents, inclusion of fathers in childcare activities and explicit measures to reintegrate mothers into the workforce. According to Women, Business, and the Law (2018), in 71 percent of the 189 economies surveyed, the government provides childcare services. Fifty percent of the surveyed countries provide non-tax benefits (child allowance), but only 30 percent provide non-tax benefits for private childcare centers. Even fewer countries, 17 percent, provide a tax deduction for childcare payments. Across all indicators of support for child care, UMIs and HIEs perform better.

Rural areas present special challenges to child care provision. Public interventions such as “Cuna Mas” in Peru and “Reach up” in Jamaica, have proven to empower rural and low-income women by providing them with facilities, nutrition and nursing services for their children, allowing them to work or attend school. However, most countries do not have the resources to extend public child care to all localities and most informal sector workers (dominating rural areas of LIEs and LMIs) would not be eligible for such centers. The diffuse population also often means a lack of critical mass to justify a childcare center. As the extended family structure breaks down due to increase mobility, migration, and other causes, the options for child care disappear. As a result, women work much longer hours—doing “economic work” when the children are in school or asleep, r they take their children with them, which often means hours in the sun near agricultural fields and little or no supervision.

Many private sector companies provide childcare services to boost recruitment and retention of women employees. Many countries—such as Chile, Turkey, Brazil and India, have legal mandates for companies to provide childcare for employers. Childcare services are one tool to change business culture. These initiatives have proven to be successful in terms of recruitment a broader talent pool –which usually entails greater gender diversity-, the reduction of turnover as well as long-term commitment to employers (IFC, 2017).

The need for childcare services presents enterprise opportunities in rural areas. The Self-employed Women’s Association (SEWA) provides early child care services as a social enterprise providing a much needed service to women working agriculture, as day labor, who are self-employed, and as employees in other SEWA enterprises. The service has resulted in improved nutrition of the children and better performance once the children enter school. The experience “demonstrates that adequate childcare encourages school-going among children and helps tackle social barriers such as caste.” Beyond support for working women, the SEWA centers provide jobs for other women as crèche teachers, etc. (Chatterjee, 2006). Many such examples exist across the world, and they are a good area for investment by governments—in the form of tax breaks, grants to support improved services, and training of workers.

Building assets—digital, financial, and property

Recommendation: G20 nations should craft policies and programs meant to create access to the modern economy that address the issues of accessibility and usability for rural women. It is not the technology alone, but the associated services and training available to use the technology.

Particularly for entrepreneurs, the drivers of the modern economy are access to digital technology for price discovery, financial services, output market entry, networking, etc.; financial services for initial and working capital and to manage risk; and (especially for agriculture, livestock, and aquaculture) access to land for production and as collateral for access to credit. For rural women, the needs vary across economy groups.

Digital. Digital technology is changing the way markets work, and for those who have access to good quality technology, it can help lower barriers to entry in markets and improve price discovery to enhance competitiveness. The challenge for rural women entrepreneurs across all country income groups is the accessibility of sufficient technology to compete. Even in many HIEs, access to broadband limits entrepreneur’s efforts to reach input and output markets efficiently and reliably. Governments need to prioritize ensuring affordable quality broadband access in the rural areas of their countries.

Recommendation: Where super-fast broadband is too expensive to deliver to individual customers, providing a super-fast hub within a public community center could facilitate rural entrepreneurs.

|

In LIEs and LMIs rural women face challenges beyond the technological access. First, pricing of the technology—smart phones, tablets, computers—can be place the technology out of reach. Many services run through SMS technology—iCow in Kenya is one such example—requiring much less capital to benefit from the service. However, there are many obstacles beyond access to technology.

The experience of Bangladesh is a good example of challenges to bridging the digital divide for rural women. While the country has good access to financial services (90% of 21 million MFI customers) for women, in 2015 only 18 percent of digital finance users were women. The reasons for this include few women agents working in mobile banking markets, potential security risks to women, lack of appropriate ID for a mobile account, actual ownership—most phones are owned by the husband or order child, and of literacy and numeracy (Shrader, 2015). BRAC tested an intensive training program—twice monthly training sessions for 10 months—for 200 women clients in rural areas. This resulted in 33 percent of the trainees becoming regular bKash users. An analysis of goMoney in Solomon Islands showed similar limitations to women’s use of the technology. It also found that having access to a steady income stream was correlated with more active and consistent use of mobile banking services—so more female customers (59%) were in full-time paid jobs or self-employed; only 38% were subsistence farmers (World Bank, 2018).

Recommendation: Increasing rural women’s access to digital technology may require a drive to get women national IDs, training to make them comfortable with the technology, literacy and numeracy training, and/or training for families to make the men of a household open to women using the technology.

Financial services. According to Global Findex, 71 percent of men have an account at a financial institution compared to 64 percent of women. The rate of people having accounts increases by 15 percent when people have secondary education. Worldwide, 66 percent of rural people have an account, but this drops to 32 percent in LIEs. Almost one in four people (23 percent) in low-income countries states that the reason for not having an account is distance (World Bank, 2018).

|

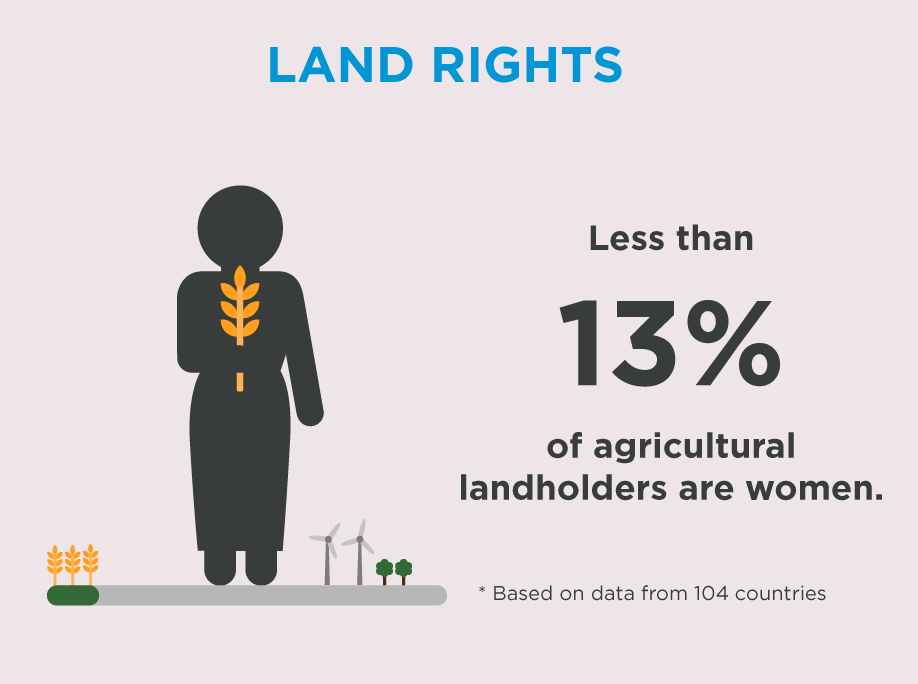

| UNWomen |

Access to credit requires collateral and/or a credit rating system, both of which can be unreachable for women in rural areas. In rural areas, one of the main forms of collateral is land, from which most women are blocked—culturally if not legally. According to UN Women (2018), fewer than 13 percent of agricultural landowners are women. Based on data from FAO, there is very little up-to-date data on land management or land ownership patterns. Table 2 below shows the data available for the G20 countries, which would be more likely to have robust data collection systems. A survey of 189 countries found that 40 percent have at least one constraint on women’s property rights (World Bank Group, 2018). The same survey found that 78 percent of the countries have no law that affirmatively gives the right to women to be a “head of household”. For unmarried women, only 21 percent of countries have that affirmative right in the law. The number drops to 5 percent for married women. Lack of credit contributes to lack of production inputs and technology, regardless of the sector. In primary cropping systems, this results in a yield gap of 20-30 percent. In enterprises out outside of agriculture, it can contribute to higher production costs and lower quality products.

| Table 2 Women’s management or ownership of agricultural land among G20 member nations | ||||

| G20 Member Nations | Agricultural Holders | Agricultural Landowners | ||

| Women as % of total | Source Date | Women as % of total | Source Date | |

| Argentina | 16.2% | 2002 | ||

| Australia | ||||

| Brazil | 12.7% | 2006 | ||

| Canada | 27.4% | 2011 | ||

| China | ||||

| France | 22.7% | 2010 | ||

| Germany | 8.4% | 2010 | ||

| India | 12.8% | 2010-2011 | ||

| Indonesia | 8.8% | 1993 | ||

| Italy | 30.7% | 2010 | ||

| Japan | ||||

| Mexico | 15.7% | 2007 | 32.2% | 2002 |

| Republic of Korea | ||||

| Russian Federation | ||||

| Saudi Arabia | 0.8% | 1999 | ||

| South Africa | ||||

| Spain | 21.7% | 2010 | ||

| Turkey | ||||

| United Kingdom | 13.1% | 2010 | ||

| United States | 13.7% | 2012 | ||

| Note: The European Union is a G20 member but not list because data is reported at the national level only. Source: FAO, 2018 | ||||

Recommendation: A priority for the G20 and other nations is to improve the collection of quality data about land ownership.

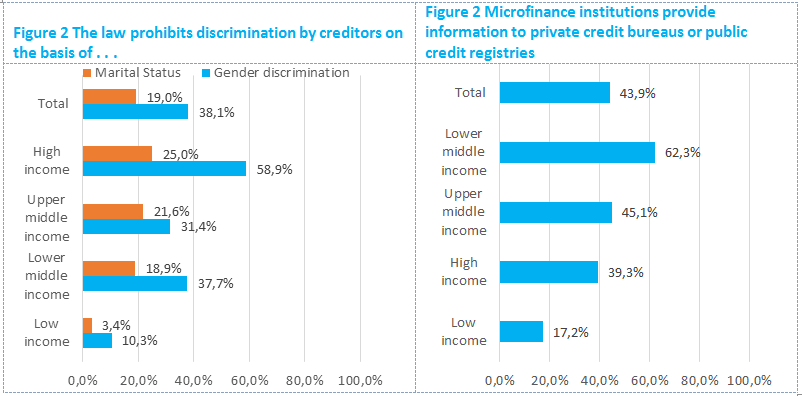

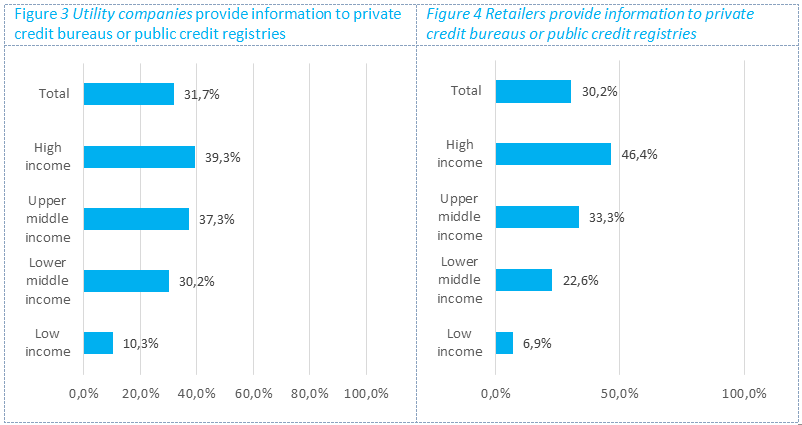

According to Women, Business, and the Law, only 19 percent of countries have laws prohibiting creditors from discrimination based on marital status, and only 38 percent ban discrimination based on gender (figure 2). There are also limited avenues to build a credit history—e.g., evidence of reliable bill payment, something that women are often responsible for in the household (figures 3-5).

Recommendation: Countries should reform inheritance laws to allow women access to property and land.

As has been acknowledged by Women, Business, and the Law, discriminatory inheritance laws undermine women’s capacity to engage in economic activities. In 36 economies, widows are not granted the same inheritance rights as men. Moreover, in 39 economies, laws prevent daughters to inherit the same proportion of assets as sons.

Control of land or housing can provide direct economic benefits to women entrepreneurs. When women have access to land, their chances to access to credit increases, as they are able to use this resource to obtain loans or microfinance, even in informal settings (Persha, L. et al., 2017). This is particular important because women tend to receive a lower income than men (due to their domestic burden), which leads to less savings and monetized contributions to invest in a small business.

Recommendation: Countries should commit to providing affirmative protection of women against discrimination by creditors, and they should establish credit rating systems that collect information on payment history to help women, in particular, build a credit history through other means.

Strengthening Visibility, Collective Voice, And Representation

Recommendation: G20 nations should commit to supporting the operation of women’s groups and networks through, for example, ensuring the legal framework for women’s organizations to have a legal identity within the country; provide support—e.g., training, grants, tax breaks, providing land or production space, etc.—for organizations to operate; and working with the networks to design policies and programs for women’s economic empowerment.

Can women achieve economic empowerment without achieving political and social empowerment? Criticisms of modern empowerment programs point to their focus on finance and assets women economically without empowering them in all other spheres of life? Certainly, legal and regulatory reforms that enshrine equal rights for women and programs that ease their unpaid labor burden are important, as is the access to finance and assets. However, focusing solely on this misses the heart of empowerment as it was envisaged by the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995:

“Absolute poverty and the feminization of poverty, unemployment, the increasing fragility of the environment, continued violence against women and the widespread exclusion of half of humanity from institutions of power and governance underscore the need to continue the search for development, peace and security and for ways of assuring people-centred sustainable development. The participation and leadership of the half of humanity that is female is essential to the success of that search.” (The United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women. 1995)

The creation of gender sensitive institutions could assist in bringing women into the forefront of both the narrative and practice of the economy (box 2). IFPRI (2017) points to the example of Heifer International which linked its asset transfer program for women to forming and strengthening women’s groups. The assets helped the women earn income, which increased agency within her household and community and the groups provided a space for women to come together, learn, and gain confidence (IFPRI, 2017).

Box 2 Networks give women collective voice and increased agency in the economic arena

| In Africa, the First Continental Conference on the Empowerment of African Women in Maritime (CCEAWM) in Luanda, Angola, in March 2015 was a huge step in creating a gender sensitive institutional platform for women involved in the maritime sectors in Africa. To create enabling institutional arrangements, states should prioritize the implementation of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This would require the international community to scale up gender sensitive investments in ocean resources. These investments should be targeted and inclusive of poor and rural coastal communities in a way that ensure that women are not only empowered but have equal access to resources. In South Asia, formal and informal networks are working to link women entrepreneurs at all levels to advocate for pro-female employment and business policies. The South Asia Women’s Development Forum brings together entrepreneurs with women’s chambers of commerce and other association to share information and advocate on women, business, and the policy environment that affects them. The informal Business Enterprise and Employment Support for Women in South Asia, has worked across national borders to facilitate women-to-women learning on technical issues for economic empowerment such as product development, product quality, business planning and management, etc. Source: authors |

One of the concepts underlying new WEFI program (2017) is that lack of networks and knowledge constrain female entrepreneurship. Certainly, social connections have long enabled men to access business opportunities. Where women can come together, build confidence, forge professional connections, and connect with mentors to help build their business (WEFI concept note).

For rural women in low income countries, such organizations and networks—that seek to empower women economically—can also help establish links to input and output markets, to productive assets, and to finance. Examples such as, SEWA, ALEAP, SABAH, and BRAC have provided the support in training, jobs, finance, and market access for women that often lack the literacy skills and agency to be successful entrepreneurs.

Recommendation: G20 Countries should promote rural women’s political participation in all levels of government.

Lack of access to resources undermine women’s political participation, which is a key element to strengthen democratic and fair societies, and create a political environment that is able to translate women’s perspective and needs into legislation. Evidence supports that when women are in office, they tend to make laws beneficial to female’s interests (Reindgold, 2000) and increase opportunities for the career of other women.

For example, in the 100 economies with a score of 100 or higher in “accessing to institutions”, Women, Business, and the Law highlighted that the proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments was 24%, whereas in the 62 economies with a score lower than 100, this percentage decreased to 17%. Some regions, such as Latin America, have experienced a backlash in women’s political participation. In 2014, there were 4 women presidents, the highest number ever experienced in the region. Currently, there is no female president. Female participation in legislative bodies in the region is 28.4% (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2017), around one fifth of all parliamentarians. The world average is 23.4%.

By promoting women’s political participation, countries encourage women’s economic empowerment.

[1] Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). 2015. Estimating women’s contribution to the economy. http://cpd.org.bd/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Estimating-Women%E2%80%99s-Contribution-to-the-Economy-Study-Summary.pdf

References

- Chatterjee, Mirai. 2006. “Decentralized Childcare Services: The SEWA Experience” Economic and Political Weekly Vol. 41, No. 34, Aug. 26 – Sep. 1, 2006: pp. 3660-3664.

- FAO. (2011). State of Food and Agriculture 2010-11. Rome, Italy. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i2050e/i2050e.pdf

- FAO, IFAD, ILO. (2010). Rural women’s entrepreneurship is “good business”! Gender and Rural Employment Policy Brief #3. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i2008e/i2008e03.pdf

- Girls Not Brides. (No date).Girls Not Brides. Retrieved from https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/region/south-asia/

- Global Markets Institute. (28. February 2014). Giving Credit Where Credit is Due. New York, United States. Retrieved from http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/public-policy/gmi-folder/gmi-report-pdf.pdf

- IFC. (2017). Tackling Childcare: The Business Case for Employer-Supported Childcare. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved from https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/bd3104e5-5a28-4ee9-8bd4-e914026dd700/01817+WB+Childcare+Report_FinalWeb3.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- IFPRI [International Food Policy Research Institute]. (2017). “How development organizations can help women’s empowerment.” Retrieved from http://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-development-organizations-can-help-womens-empowerment

- ILO. 2010. Rural women’s entrepreneurship is “good business”!. Gender and Rural Employment Policy Brief #3

- International Labor Organization (ILO). (2016). Women at Work: Trends 2016. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_457317.pdf

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. “Women in Parliament in 2017. The year in review” Retrieved from: https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/reports/2018-03/women-in-parliament-in-2017-year-in-review

- May, M. A. (29. October 2015). How hard is it to use mobile money as a rural Bangladeshi woman? Dhaka, Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://blog.brac.net/mobilise-money-rural-bangladeshi-woman/

- Mollard, I. a.-L. (2015). Beyond quality at entry: portfolio review on gender implementation of agriculture projects (FY08-13). Washington, DC: World Bank (mimeo). Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/970641468339041989/Beyond-quality-at-entry-portfolio-review-on-gender-implementation-of-agriculture-projects-FY08-13

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (June 2016). Tracking the money for women’s economic empowerment: still a drop in the ocean. OECD DAC NETWORK ON GENDER EQUALITY (GENDERNET). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/Tracking-the-money-for-womens-economic-empowerment.pdf

- Persha, L., Greif, A., Huntington, H. (2017). Assessing the impact of second-level land certification in Ethiopia. In: Paper prepared for presentation at the 2017 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. The World Bank, Washington DC (March 20–24, 2017).

- Reindgold, B. (2000). Representing Women: Sex, Gender, and Legislative Behaviour in Arizona and California. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

- Shrader, L. (2015). Digital Finance in Bangladesh: Where are all the Women? Washington, DC, United States: Consultative Group to Assist the Poorest (CGAP). Retrieved from http://www.cgap.org/blog/digital-finance-bangladesh-where-are-all-women

- Schneider, F. (2002). Size And Measurement Of The Informal Economy In 110 Countries Around The World. paper was presented at an Workshop of Australian National Tax Centre, ANU, Canberra, Australia in July 17, 2002. http://www.amnet.co.il/attachments/informal_economy110.pdf

- The United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women (1995). Platform for Action. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/plat1.htm#objectives

- UN Global Compact, UN Women. (March 2010). Women’s Empowerment Principles. Retrieved from http://www.weprinciples.org/Site/PrincipleOverview/

- UN Women. (February 2018). Learn the Facts: Rural Women and Girls. New York, United States. Retrieved from http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/multimedia/2018/2/infographic-rural-women

- Vyzaki, M., & van de Velde, P. (31. October 2017). How to identify legal barriers to women’s participation in agriculture. Washington, DC, United States: World Bank.

- World Bank. (2009). Gender in Fisheries and Aquaculture. Gender in Agriculture Sourcebook. Washington, DC, United States. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/799571468340869508/pdf/461620PUB0Box3101OFFICIAL0USE0ONLY1.pdf

- World Bank. (16. November 2015). SMEs Financing: Women Entrepreneurs in Ethiopia. Washington, DC, United States. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/11/16/financing-women-entrepreneurs-in-ethiopia

- World Bank Group. (2016). World Bank Group Gender Equality, Poverty Reduction, and Inclusive Growth. World Bank Group. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/820851467992505410/pdf/102114-REVISED-PUBLIC-WBG-Gender-Strategy.pdf

- World Bank Group. (2017). World Development Indicators. Washington, DC, United States. April 2018

- World Bank Group. (2017b). FUTURE of FOOD: Shaping the Food System to Deliver Jobs. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/406511492528621198/pdf/114394-WP-PUBLIC-18-4-2017-10-56-45-ShapingtheFoodSystemtoDeliverJobs.pdf