The brief highlights the interlinkages between child labour and human development and describes how ending economic deprivations, universalizing school education, expanding the coverage and improve the adequacy of social protection systems, and ensuring private sector engagement in protecting child rights can effectively eliminate child labour and promote inclusive growth and development. Evidence-informed, multi-sectoral, scalable solutions are presented that can ensure children are protected from economic exploitation and end the perpetuation of long-term cumulative deprivation. The brief presents actionable policy recommendations for the G20, drawing from the most recent global research and evidence on ending child labour.

Challenge

Child labour violates the rights and dignity of children. It is detrimental to the formation of human capabilities with irreversible intra- and inter-generational consequences. Ending child labour, therefore, should become a marker of human progress. Every society should enable children to realise their full potential by leading a healthy life, enjoying bodily integrity free of abuse, using their senses to develop intellectually, and engaging in social interactions as they safely transition into adulthood.

Despite purposive public actions, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), ILO international conventions, SDG 8.7, and national laws and policies committing to end child labour, the phenomenon of child labour persists globally. Global estimates in 2021 (ILO and UNICEF, 2021) highlight a decline in numbers worldwide, but also stagnation in progress. While the number of children in child labour dropped from 246 million in 2000 to 160 million at the beginning of 2020, progress has slowed since 2012. Between 2016 and 2020, the global child labour rate remained unchanged, translating into an increase of 8.4 million children in labour. Approximately 79 million children in 2020 were performing hazardous work. All regions have experienced progress except for Sub-Saharan Africa, where prevalence of child labour has increased since 2012, reaching 23.9 percent (86.6 million children) at the beginning of 2020.

Worldwide, about 70 percent of children in child labour work in agriculture, 10 percent in industry, and 20 percent in services. The share of children in child labour who work within the family has also increased from 63 percent in 2016 to 72 percent in 2020. Notably, a significant share of child labour within the household is hazardous. Beyond its detrimental effects on children, child labour depresses adult wages and lowers a country’s investment in new technologies (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019).

With the outbreak of COVID-19, the risk of child labour has surged, mostly due to economic and health shocks, as well as protracted school closures (Memon et al., 2020). In Uganda, for example, the prevalence of child labour increased from 21 to 36 percent during the COVID-19 pandemic (UBOS, 2021). Working conditions typically deteriorated, which many children were forced to accept given the scarcity of both educational and economic opportunities during lockdowns (Ko Ko and Oo, 2022). Following the staggered re-opening of schools, children from more marginalized communities are at higher risk of not returning to the classroom or subsequently dropping out (World Bank et al., 2022), which further increases their child labour risk.

Proposal

What is needed to end child labour

Household poverty, inadequate access to education and skills development, discriminatory social and gender norms, informal labour markets, as well as unethical business practices, all drive child labour.

Countries with higher levels of poverty generally have higher child labour rates (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019). Child labour is more prevalent in economies with high levels of informality, where working conditions are inadequately regulated. Child labour risks also increase in complex supply chains, especially in the absence of due diligence and conscious efforts by the private sector to protect child rights.

Conversely, improved access to early childhood and secondary education is associated with lower child labour. This is not the case, however, if school quality is poor or if households cannot afford the costs of education.

Social and cultural norms also play a key role in mediating household economic decisions, including child participation in productive activities. Social norms around girls’ schooling and time-use can, in particular, deter their school attendance and hinder the beneficial effect of schooling access on child labour (Abdullah et al., 2022). Indeed, girls under the age of 14 are likely to spend between 30 to 50 percent more time than boys in household chores (UNICEF, 2016). While often not counted in child labour statistics, household chores can divert significant time from school attendance or studying at home, especially when carried out for long hours. Moreover, chores can be hazardous too. For example, fetching water likely entails carrying heavy loads for prolonged time under extreme temperatures, or cooking may entail being exposed to smoke due to inefficient cooking stoves.

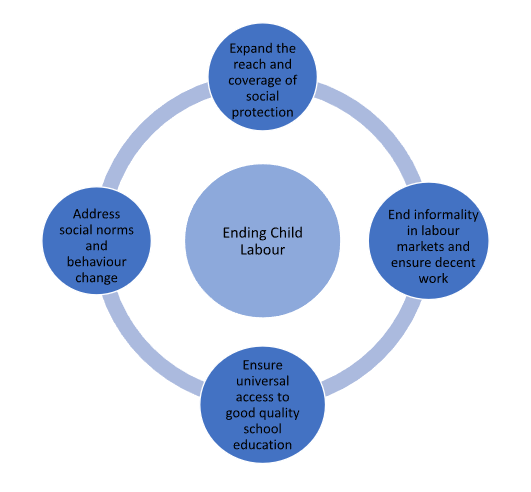

Ending child labour calls for a multi-sectoral response by the state, private sector, and communities to support children and families. Figure 1 identifies four essential, urgent, and mutually supportive intervention areas that address drivers of child labour for children, families, and communities including wider societal and economic factors. None of these intervention areas can work in isolation. Moreover, these primary interventions need to be strengthened by actions to identify and reach the most vulnerable children, such as those who migrate seasonally with families, or separated from families for a variety of reasons, and for whom targeted strategies and social welfare support is essential (UNICEF, 2021). Taken together, they represent an agenda the G20 countries can champion through both investment and advocacy to eliminate child labour.

Figure 1: Priorities to End Child Labour: A Call to Action for the G20

1. Expand the coverage of social protection and improve programme design

Well-designed social protection is an essential element of an effective strategy to reduce child labour. Coverage of and investment in social protection remains low in many countries, with significant regional disparities and a limited focus on children.[1] It is, therefore, essential to increase coverage for children through strengthening investments in social protection systems that can respond to the needs of children and their families. Social protection systems must address the diverse vulnerabilities of households across the life-course, including, for instance, providing unemployment protection, health insurance, disability protection, and old-age pensions.

Social protection programmes demonstrate mostly protective effects on child labour (ILO and UNICEF Innocenti, 2022). However, some programme studies show no effect on child labour. Other studies show mixed effects (increasing some forms of work and reducing others), or even increases in children’s work, including some of its worst forms. This can occur when benefit amounts are inadequate for a given context, for example, when they are insufficient to cover the full cost of schooling, including foregone earnings from child labour (e.g., Prifti et al, 2020; de Hoop et al., 2019), or when households invest part of the benefits in productive assets (such as livestock or land) which may increase the demand for child labour, especially when households have limited awareness of the hazards from child labour (e.g., de Hoop et al., 2020a, b; Sulaiman, 2015)[2].

To ensure reductions in child labour, therefore, social protection programmes need to explicitly take child rights and labour considerations into account. Specific recommendations include expanding coverage through universal and unconditional transfers, ensuring adequate amounts and regularity of transfers, combining cash benefits with complementary services including in the education, health, and child protection sectors (ILO and UNICEF Innocenti, 2022).

2. Ensure universal access to quality education

Globally, universalisation of school education has been associated with declines in child labour. For instance, over the past two decades the decline in the global child labour rate has been accompanied by reductions in the prevalence of out-of-school children and improvements in the rate of primary school completion (see Figures A1 and A2 in the Appendix). For the education sector to fulfil its potential in preventing and reducing child labour, there need to be concerted efforts to prevent dropout from school, integrate current child labourers into school, and provide appropriate skills for older adolescents to safely transition into post-schooling work or education. There also needs to be specific consideration that children may be both enrolled in school and working, in a way that is detrimental to their learning and development. In the context of COVID-19 and other protracted crises, expanding age-appropriate and equitable access to digital tools and resources through improving electrification and accessibility of resources is an emerging challenge (Brossard et al., 2021).

Reducing the opportunity costs of schooling is essential to reduce child labour particularly for secondary school age children. Integrating cash transfers with education supply-side interventions can boost the protective impact of cash transfers with respect to child labour (Emezue et al., forthcoming; ILO and UNICEF Innocenti, 2022). Removing school fees also reduces child labour (Tang et al., 2020). Similarly, merit-based scholarships and school vouchers can improve school participation and reduce working hours if their value is appropriately set. Evidence from Nepal and Indonesia shows that higher-value scholarships reduce child work and labour while lower-value ones are ineffective particularly for older children (Datt and Uhe, 2019; Sparrow, 2007). School feeding (school meals or take-home rations) also proved effective to improve schooling and reduce children’s work (e.g., Aurino et al., 2019; Kazianga et al., 2012).

School reforms that a) increase the length of the school day including for extra-curricular activities, b) extend the duration of schooling by expanding access to Early Childhood Education (ECD), and c) increase the availability of, and reduce distance to middle and secondary schools in particular, through improving public transportation can increase children’s time in education and reduce the time available for work (Kozhaya and Martinez Flores, 2020; Martinez et al., 2017; Vuri, 2010). ECD interventions, in particular, strengthen foundational learning from an early age, thus facilitating age-appropriate enrolment, retention, and participation in primary school. There is also evidence that ECD reduce caring activities by older siblings in lower secondary school ages, who can subsequently focus their time and attention on their schooling (Martinez et al., 2017).

However, expanding schooling access and increasing children’s time in school will not be effective in reducing child labour if education is not of good quality or does not represent a meaningful use of children’s time.

Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET), combining education and apprenticeship, can prevent premature dropout and ensure safe transition into labour markets, as it can help children age 15 and above to acquire skills, knowledge, and mindsets needed to subsequently enter and thrive in the world of work. Successful TVET combines school-based learning with work-based training in a legally defined manner, building access to decent work for children who have reached the minimum age of employment. It requires robust collaboration with the private sector, which also results in cost-sharing and reduces the cost burden of education on youth and their families. UNICEF’s 2018 Turkey initiative in collaboration with Turkish Tradesmen and Handicrafts showed that “apprentices are not workers but students” and can therefore benefit from the protective and supportive features of technical and vocational training (UNICEF, 2018).

3. Address discriminatory social and gender norms and improve awareness on children’s rights

While education policies, legislation, and investments can go a long way in ensuring universal access to quality education, they may be insufficient to tackle deeper rooted norms that see children’s work as both appropriate and necessary. Complementary social and behaviour change strategies are necessary, for instance, to challenge girls’ excessive engagement in domestic work, and the use of children’s labour to supplement household incomes.

Such strategies can include school-based training and mentoring sessions to increase children’s awareness on the returns to education and hazards related to child labour, as well as to promote children’s agency and decision-making around education, labour, and marriage. As most child labour occurs within a child’s household, engaging parents and caregivers is critical. This can be done, for example, through in-person awareness-building sessions with parents, or distance interventions including messaging via mobile phones or tablets. Village-level groups and committees including adolescents and their caregivers, or broader campaigns to encourage school participation and discourage work represent other relevant interventions to shift awareness and norms.

While the role of social norms is widely acknowledged, rigorous evidence on the effectiveness of the above-described interventions to reduce child labour remains limited. Two studies in Ghana and Peru reported mixed effects on children’s work, depending on the type of work considered, or the modalities of intervention delivery, or regional differences in logistical infrastructures (Berry et al., 2018; Gallego et al., 2018). Evidence from India showed that an intervention promoting adolescent girls’ awareness on their rights and providing training on life skills (e.g., self-confidence, perseverance) was effective in improving girls’ schooling outcomes but did not change their labour outcomes (Edmonds et al., 2021).

All these studies estimate impacts after a relatively short intervention duration (nine months to two years). This may also explain the weak evidence on effectiveness, as it is expected that longer-term engagement is needed to generate changes in social norms.

4. Design inclusive economic frameworks and ensure decent work for all

That child labour is present even in wealthier countries signals that high incomes and economic growth are not sufficient for ending child labour. Child labour can be eliminated only through inclusive development and strong social service systems, including in the areas of education, social and child protection (ILO and UNICEF, 2021).

Moving away from informal to more formalized market structures is critical to reduce child labour (Edmonds, 2005; Basu, 1999). Locating production outside the home and offering new alternatives to production for goods traditionally produced by child labour should be embedded in growth strategies and market expansion. Shifts to formal economies are also accompanied by comparatively stronger tax bases, introducing greater resources for financing social protection and education services that can prevent and reduce child labour (ILO and UNICEF, 2021).

The private sector is an essential partner in eradicating child labour. While government regulators have a prominent role in ensuring adequate and just working conditions, business leaders have a responsibility to investigate the involvement of child labour in their respective sectors and contribute to eliminating child labour and promote children’s wellbeing (WBCSD and UNICEF, 2021). Paying adequate living wages to adult workers and farmers and ensuring sufficient returns to micro, small, and medium enterprises across the supply chain are key to ensure families can afford to send their children to school and not to work. These operating modalities also have a specific business rationale, as companies that operate ethically and have a positive impact on the society at large are more likely to sustain their operations in the long term.

These considerations are especially important because child labour is disproportionately found in informal micro- and small enterprises, often within a child’s own household (ILO, 2019; ILO and UNICEF, 2021). Moreover, as girls are generally more likely to engage in home-based work, addressing child labour in household production and small-scale businesses allows faster progress in reducing girls’ work which may otherwise remain invisible.

Companies across various agricultural subsectors are increasingly recognizing the importance of ensuring adequate remuneration and working conditions across the supply chain. This, in turn, can disrupt the market with consumers favouring new business models that recognize and protect children’s rights. However, there remain areas with high prevalence (“hotspots”) of child labour in key sectors, such as farming (e.g., cocoa, coffee, cotton, sugarcane, tea, tobacco), mining (e.g., gold, mica, cobalt), garment sewing, brick making, and construction (see, for instance, SOMO and Terre des Hommes, 2018; Venkateswarlu, 2020).

Collective industry-wide actions by private sector, not just by individual businesses, in collaboration with governments and other stakeholders, is critical to accelerate progress towards ending child labour. Government – private sector collaboration is especially relevant to promote companies’ investment in strengthening public systems, including as pertains to education and child protection services. Embedding actions in a strong commitment to child protection systems, including laws, budgets, case management and referral, is essential to create a strong safety net that can ensure no child is placed in a situation of precarity and harm.

Conclusion

The G20 can commit and lead the way in supporting:

- Expansion of child-sensitive social protection;

- Increased investments in strengthening the availability and quality of education from foundational through elementary and secondary education;

- Strategies to end discriminatory social and gender norms;

- Equitable conditions and standards in the labour market, through collaboration between government regulators and private companies; and

- Strengthened child protection laws and systems ensuring identification, support, and school re-integration of children in child labour.

- Investment in research to further improve our understanding of the most promising, effective, and scalable strategies to accelerate results.

In particular, countries should focus investments on building foundational learning for all children, and specifically benefiting adolescent girls who are vulnerable to early marriage, school dropout and early labour. Prioritised and urgent attention, led by the G20, holds the key to ending child labour to meet both present and future human capital needs and human development challenges.

References

Abdullah, A., Huynh, I., Emery, C. R., and Jordan, L. P. (2022). Social norms and family child labour: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 4082.

Aurino, E., Tranchant, J. P., Sekou Diallo, A., and Gelli, A. (2019). School feeding or general food distribution? Quasi-experimental evidence on the educational impacts of emergency food assistance during conflict in Mali. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(sup1), 7-28.

Basu, K. (1999). Child labour: Cause, consequence, and cure, with remarks on International Labour Standards. International Journal of Economic Literature, 37, 1083-1119.

Basu, K., Das, S., and Dutta, B. (2010). Child labour and household wealth: Theory and empirical evidence of an inverted-U. Journal of Development Economics, 91(1), 8-14.

Berry, J., Karlan, D., and Pradhan, M. (2018). The impact of financial education for youth in Ghana. World Development, 102, 71-89.

Brossard, M., Carnelli, M., Chaudron, S., Di-Gioia, R., Dreesen, T., Kardefelt-Winther, D., Little, C., and Yameogo, J. L. (2021). Digital learning for every child: Closing the gaps for an inclusive and prosperous future. Innocenti Working Papers.

Datt, G., and Uhe, L. (2019). A little help may be no help at all: Size of scholarships and child labour in Nepal. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(6), 1158-1181.

De Hoop J., Friedman, J., Kandpal, E., and Rosati, F. C. (2019). Child schooling and child work in the presence of a partial education subsidy. Journal of Human Resources, 54(2), 503-531.

De Hoop, J., Gichane, M. W., Groppo, V., and Zuilkowski, S. S. (2020a). Cash transfers, public works and child activities: Mixed methods evidence from the United Republic of Tanzania. Innocenti Working Papers, No. 2020-03.

De Hoop, J., Groppo, V., and Handa, S. (2020b). Cash transfers, microentrepreneurial activity, and child work: Evidence from Malawi and Zambia. World Bank Economic Review, 34(3), 670-697.

Dumas, C. (2013). Market imperfections and child labor. World Development, 42, 127-142.

Edmonds, E. V. (2005). Does child labor decline with improving economic status? Journal of Human Resources, 40(1), 77-99.

Edmonds, E. V., Feigenberg, B., and Leight, J. (2021). Advancing the agency of adolescent girls. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1-46.

Emezue, C., Pozneanscaia, C., Sheaf, G., Groppo, V., Bakrania, S., and Kaplan, J. (forthcoming). The impact of educational policies and programmes on child work and child labour in low-and-middle-income countries: A rapid evidence assessment. Innocenti Working Papers.

Gallego, F., Molina, O., and Neilson, C. (2018). Choosing a Better Future: Information to Reduce School Drop Out and Child Labor Rates in Peru. Innovations for Poverty Action. https://www.poverty-action.org/sites/default/files/publications/Peru-Returns-to-Education-Brief-English-Sept-2018.pdf

ILO (International Labour Organization) (2019). Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—Ipek/documents/publication/wcms_716930.pdf

ILO (International Labour Organization) (2021). World Social Protection Report 2020–22: Social protection at the crossroads ‒ in pursuit of a better future. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—reports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_817572.pdf

ILO (International Labour Organization) and UNICEF (2021). Child labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward. https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-labour-2020-global-estimates-trends-and-the-road-forward/#:~:text=63%20million%20girls%20and%2097,first%20time%20in%2020%20years

ILO (International Labour Organization) and UNICEF Innocenti (2022). The role of social protection in the elimination of child labour: Evidence review and policy implications. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—Ipek/documents/publication/wcms_845168.pdf

Kazianga, H., De Walque, D., and Alderman, H. (2012). Educational and child labour impacts of two food-for-education schemes: Evidence from a randomised trial in rural Burkina Faso. Journal of African Economies, 21(5), 723-760.

Ko Ko, T., and May Oo, K. (2022). The impacts of Covid-19 on the worst forms of child labour in Myanmar. Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/17339/The_Impacts_of_Covid-19_on_the_Worst_Forms_of_Child_Labour_in_Myanmar_FunderRep.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Kozhaya, M., and Martinez Flores, F. (2020). Schooling and child labor: Evidence from Mexico’s full-time school program. Ruhr Economic Papers, 851.

Martinez, S., Naudeau, S., and Pereira, V. A. (2017). Preschool and child development under extreme poverty: Evidence from a randomized experiment in rural Mozambique. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 8290.

Memon, A. S., Rigole, A., Nakashian, T. V., Taulo, W. G., Chávez, C., and Mizunoya, S. (2020). COVID-19: How prepared are global education systems for future crises? Innocenti Research Briefs, 2020-21.

Prifti, E., Daidone, S., Campora, G., and Pace, N., (2020). Government transfers and time allocation decisions: The case of child labour in Ethiopia. Journal of International Development, 33(1), 16-40.

SOMO and Terre des Hommes (2018). Global Mica Mining and the Impact on Children’s Rights. https://www.somo.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/NL180313_GLOBAL-MICA-MINING-.pdf

Sparrow, R. (2007). Protecting education for the poor in times of crisis: An evaluation of a scholarship programme in Indonesia. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(1), 99-122.

Sulaiman, M. (2015). Does wealth increase affect school enrolment in ultra-poor households: Evidence from an experiment in Bangladesh. Enterprise Development and Microfinance, 26(2), 139-156.

Tang, C., Zhao, L., and Zhao, Z. (2020). Does free education help combat child labor? The effect of a free compulsory education reform in rural China. Journal of Population Economics, 33(2), 601-631.

Thévenon, O., and Edmonds, E. (2019). Child labour: Causes, consequences and policies to tackle it. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 235.

UBOS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics) (2021). Uganda National Household Survey 2019/2020. https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/09_2021Uganda-National-Survey-Report-2019-2020.pdf

UNICEF (2016). Harnessing the power of data for girls. https://data.unicef.org/resources/harnessing-the-power-of-data-for-girls

UNICEF (2018, June 12). Technical and Vocational Education and Training as a tool against child labour [Press release]. https://www.unicef.org/turkiye/en/press-releases/technical-and-vocational-education-and-training-tool-against-child-labour

UNICEF (2021). Ending child labour through a multisectoral approach. https://www.unicef.org/media/111686/file/Child%20Labour%20Brief%20Dec%202021%20Final.pdf

Venkateswarlu, D. (2020). Sowing Hope. Child labour and non-payment of minimum wages in hybrid cottonseed and vegetable seed production in India. https://arisa.nl/wp-content/uploads/SowingHope.pdf

Vuri, D. (2010). The effect of availability of school and distance to school on children’s time allocation in Ghana. Labour, 24, 46-75.

WBCSD (World Business Council for Sustainable Development) and UNICEF (2021). Tackling Child Labour: An Introduction for Business Leaders. https://www.wbcsd.org/contentwbc/download/13450/196400/1

World Bank, UNICEF, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) (2022). The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/e52f55322528903b27f1b7e61238e416-0200022022/original/Learning-poverty-report-2022-06-21-final-V7-0-conferenceEdition.pdf

- Global social protection coverage is still low at 46.9 percent of the population, ranging from 17.4 percent in Africa to 83.9 percent in Europe and Central Asia (ILO, 2021). Only 26.4 percent of children receive at least one social protection benefit. At the global level, only 12.9 percent of GDP is spent on social protection, with social protection for children receiving significantly lower resources, at 1.1 percent of GDP. ↑

- This is often related to difficulties by households in hiring adult labour, which in turn is due to poverty, lack of local labour supply or other labour market imperfections (Dumas, 2013). ↑