Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows are at a low point as a result of not only the COVID-19 pandemic but also restrictive FDI policies adopted in recent years. Investment facilitation has gained in importance as a set of practical measures to increase the transparency and predictability of investment frameworks and promote cooperation to advance development. Investment facilitation can help to reduce the transactional and administrative costs faced by foreign investors. Discussions on a distinct set of investment facilitation policies and measures have gained momentum in recent years. Negotiations are undertaken at the bilateral and regional levels, for example, in the context of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) or the Sustainable Investment Protocol of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). Another important initiative is underway among members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) which are negotiating an Investment Facilitation Framework for Development. This policy brief develops a set of key recommendations for G20 policy-makers on how investment facilitation frameworks can be designed to help attract sustainable FDI for sustainable development and recovery in general. These recommendations can be summarized in three guiding principles that should be promoted by the G20: contribute directly to sustainable development, focus on conflict prevention and management, and learn from experiences from other processes such as trade facilitation.

Challenge

Foreign direct investment (FDI) collapsed in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the outlook for 2021 is bleak.1 Global FDI fell by a staggering 42 per cent in 2020, from $1.5 trillion in 2019 to approximately $859 billion, reaching its lowest level in over fifteen years, more than 30 percent lower than following the 2008-9 global financial crisis (UNCTAD, 2021). Developing countries fared better relative to developed economies, but FDI still fell by 37 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean, 18 per cent in Africa and 4 per cent in Asia (although in some G20 Asian economies FDI actually went up in 2020, including in China, India and Japan). However, the outlook for developing economies in 2021 is worrisome, as greenfield FDI announcements fell by 46 per cent overall, with some regions experiencing even sharper contractions, for instance Africa by a staggering 63 per cent.

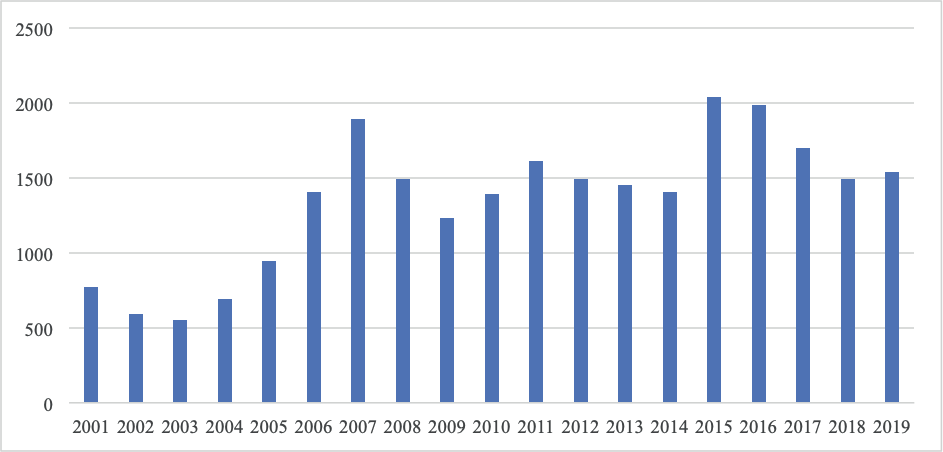

In addition, even before COVID-19, global FDI was “on the ropes” for the previous five years, falling by almost a quarter (25 per cent) between 2015 and 2019 (see Figure 1, red circle). This reflects a mix of factors, including a decline in average rates of return on investment and less supportive outward and inward FDI policies in many countries (Evenett and Fritz, 2021).

Figure 1. Global FDI inflows (2001-19, USD billions)

Source: authors based on UNCTATStat

Pre-pandemic trends and the consequences of the pandemic necessitate a discussion of the kinds of policies and frameworks that are needed to facilitate FDI. Of special importance are policies that help to encourage and retain investment that directly advances sustainable development, reducing risks from future disasters and crises. Although COVID-19 was a major negative shock to FDI flows, a large FDI stock underpinning international production networks helped to ensure the resilience of global value chains producing a broad range of agricultural, energy and manufactured goods and digital services that continued to be provided throughout the pandemic.

Rebooting FDI flows will be an important element of economic recovery and in making the slogan “building back better and greener” a reality across the globe. A necessary condition is a supportive policy framework in both home and host countries that is sensitive to the role FDI can play in realizing the UN SDGs. This framework spans both the substance of FDI policies and their administration. Although this policy brief is limited to facilitation reducing the transactional and administrative costs faced by foreign investors it is important to recognize that restrictive FDI policies in home and/or host countries may reduce the positive effects of facilitation efforts.

Encouraged by the G20’s Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking (G20, 2016), discussions on a distinct set of investment facilitation policies and measures have gained momentum in recent years. Investment facilitation can be understood as a set of measures concerned with, among other things, improving the transparency and predictability of investment frameworks, streamlining procedures related to foreign investors and enhancing coordination and cooperation all with a view towards advancing development. More transparent and predictable investment frameworks can reduce transactions costs for investors and thus help attract and retain investment.

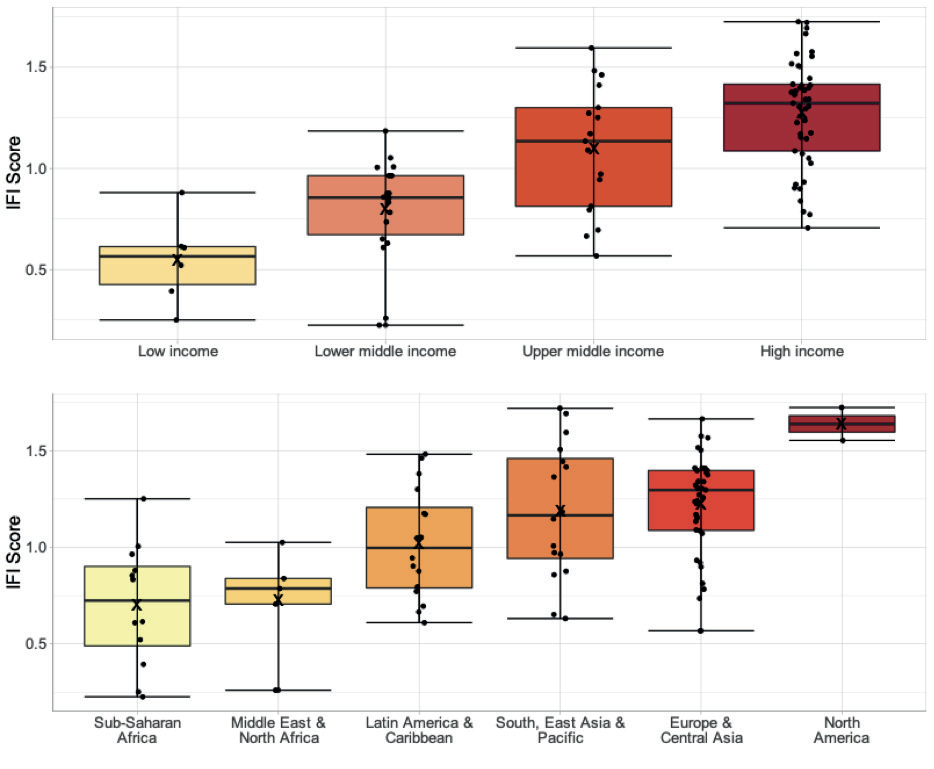

Figure 2. Investment Facilitation Index (IFI) scores for different income levels and regions, 2020

Note: Whiskers illustrate the min/max values, boxes show first/third quartile, horizontal bar represents the median while x the average for respective group Source: Berger, Dadkhah and Olekseyuk (forthcoming)

Despite the rising attention to the importance of facilitative investment policy frameworks, the actual adoption of investment facilitation measures is highly uneven across countries. Data from the Investment Facilitation Index (IFI) on the adoption of over 100 investment facilitation measures in more than eighty countries (Berger, Dadkhah and Olekseyuk, forthcoming) suggests that countries which have lower levels of adoption belong to the low-income and lower-middle-income country groups and are often located in Africa and the Middle East. The strong correlation between levels of FDI and the IFI score shows that those countries with the lowest levels of FDI, and thus in need of additional policy tools to attract FDI, have the lowest adoption levels when it comes to investment facilitation measures.

The low level of adoption of investment facilitation measures in the countries that need FDI the most to achieve the SDGs while recovering from the pandemic suggests that a better alignment of policy approaches on different levels is needed. Relying solely on unilateral investment facilitation reforms may not be enough to make a difference. Binding and non-binding rules on investment facilitation at the regional or multilateral level are important to incentivize and guide reforms at the national and subnational levels, but they have to be met with the willingness and capacity to implement them on the ground.

Investment facilitation efforts at different levels should be designed to be mutually reinforcing and complementary. This can take place through clearly identifying measures at different levels, creating mechanisms of dialogue and cooperation, and thinking about whether some measures may be particularly important at certain levels. To illustrate, standard setting may need to take place at the multilateral or regional level for it to help with investment facilitation, while aftercare and problem solving may need to be carried out at the subnational or national level, especially if the issue relates to subnational or national policy-making.

Building on previous work of the T20 (Berger et al., 2018; Stephenson et al., 2020), this policy brief develops a set of key recommendations for G20 policy-makers on how investment facilitation frameworks can be designed to support the attraction of sustainable FDI for sustainable development and recovery in general. Investment facilitation frameworks predominantly focus on attracting more FDI while often failing to include provisions that specifically aim at attracting FDI that directly contributes to sustainable development. The brief suggests key elements in this regard, regardless of whether the framework is a subnational, national, regional or multilateral one. Of critical importance is engaging an epistemic community to support the implementation of investment facilitation measures while identifying the specific needs of developing countries. The G20 should leverage opportunities to build on existing public-private multi-stakeholder initiatives to enhance the contribution of investment facilitation frameworks to sustainable development, mandating the G20 Trade and Investment Working Group (TIWG) to focus on the issue of investment facilitation during the Italian presidency and beyond. We suggest that the G20 initiates a dialogue process with the goal of providing high-level guidance on how investment facilitation frameworks can support sustainable development and recovery.

Proposal

OVERVIEW OF INVESTMENT FACILITATION INITIATIVES

Discussions on investment facilitation policies are underway at the subnational, national, bilateral, regional and multilateral levels. Almost every country has a national investment promotion agency (IPA). In addition, subnational investment facilitation has grown as investment facilitation may be especially effective at the subnational level. Subnational IPAs have boomed in the past twenty years and the number of subnational IPAs is far larger than the number of national IPAs (Knight, 2018). In a mapping by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of its economies, 15 per cent of national IPAs were found to have more than ten subnational offices. The OECD (2018) concluded from IPA survey responses that the “sub-national level primarily focuses on the provision of facilitation and aftercare services for foreign investors”.

In addition, a number of policy instruments have been adopted at the regional and international levels, often driven by developing countries. They include non-binding action plans or protocols adopted by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), G20 and Mercosur. In addition, developing countries have launched bilateral or regional investment facilitation agreements. Brazil’s programme to negotiate Cooperation and Facilitation Investment Agreements (CFIAs), the most recent example being the treaty with India concluded in 2020, is a case in point. The European Union, too, is increasingly integrating comprehensive investment facilitation provisions in its bilateral and regional agreements currently under negotiation, for example with Angola and the Eastern and Southern Africa countries.

Investment facilitation provisions are also increasingly included in regional treaties and forums. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) among countries from the Asia-Pacific includes a section on investment facilitation provisions for the promotion of the transparency and predictability of the members’ investment frameworks as well as the streamlining of administrative procedures. It also envisages the establishment of focal points to assist investors and mechanisms to prevent and resolve investment disputes through grievance management systems. The investment facilitation provisions of the RCEP are not binding and are subject to domestic laws.

The Mercosur Protocol on Investment Cooperation and Facilitation, signed by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay in April 2017, brings a new approach to investment treaty making. Modelled after the Brazilian CFIA template and aimed at establishing a transparent, agile and conducive business environment, the protocol includes a set of measures aimed at facilitating intra-regional investments. These include transparency and exchange of information on business opportunities, focal points or ombudsperson-type mechanisms tasked with supporting investors from one country in the territory of the other nations, as well as state-to-state procedures before the protocol’s Joint Commission to prevent investment disputes. The agreement has so far only entered into force for Brazil and Paraguay, and further steps are needed to implement the protocol.

Africa has been at the forefront of investment facilitation initiatives, in particular since the adoption of the 2016 Pan-African Investment Code (PAIC), which shifted emphasis from investment protection to investment facilitation. In the African context, investment facilitation is seen as the best tool to foster sustainable and responsible investment. However, the African investment landscape has been characterized by fragmentation. The need for more consistent and predictable rules has become even more evident since March 2021 with the launch of the negotiations of the future Sustainable Investment Protocol to the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). The protocol, which represents the first-ever effort to adopt a binding legal framework at a continental level to deal with investment flows, will focus mostly on investment facilitation for sustainable development.

An ambitious investment facilitation initiative is underway in the World Trade Organization (WTO). Negotiations among more than 100 members on an Investment Facilitation Framework for Development (IFF4D) began in September 2020. The negotiations are open to all members, and the hope is that, eventually, the result will be a binding multilateral agreement. The ambition is furthermore to have the principal elements of an IFF4D ready in time for the WTO’s 12th Ministerial Conference, taking place from 30 November to 3 December 2021. Excluded from the scope of the agreement are issues related to market access, investment protection and investor-state dispute settlement. Thus, the negotiations draft so far enumerates, among others, measures related to transparency of investment measures, streamlining and speeding up administrative procedures, focal points, domestic regulatory coherence and cross-border cooperation, and special and differential treatment for developing and least-developed countries. All these measures are meant to increase the flow of FDI which, in turn and on balance, helps to advance development. The draft agreement is, however, short of measures that also specifically encourage the flow of sustainable FDI, that is, investment that, while being commercially viable, involves best efforts towards directly making a reasonable contribution to the economic, social and environmental development of host countries, and that takes place in the context of fair governance mechanisms. However, as a first step with this purpose in mind, the agreement is likely to promote the voluntary uptake of responsible business conduct practices by international investors. Moreover, special and differential treatment is likely to be a key characteristic, perhaps patterned on the model of the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) (Hoekman, 2021).

International frameworks on investment facilitation can help guide and drive reforms at the national level to attract FDI (Sauvant, 2019). Most developing countries are seeking to position themselves in this new post-pandemic environment to attract and retain FDI. In the current global context, business as usual may not be enough. Countries may need to undertake domestic reforms, including structural reforms, to facilitate sustainable FDI inflows. The key question becomes how to improve the investment climate to be able to bring in more foreign investment that can contribute to sustainable growth. But the political economy at the domestic level may be challenging. In this respect, international standards embodied in investment facilitation frameworks especially if they are linked to technical assistance and capacity building can help governments raise the bar on best practices worldwide, learning from and enabling the adoption of key measures. Furthermore, anchoring domestic reforms in shared international commitments provides a commitment device to make reform more credible and sustainable.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES TO FACILITATE SUSTAINABLE FDI

International discussions on investment facilitation are in full swing, but they often lack a dedicated focus on the promotion of FDI in support of sustainable development, do too little to prevent disputes between investors and governments, and could do better to learn from past experiences of trade facilitation. In the light of these observations, we suggest the following three key guiding principles for G20 policy-makers to consider and promote.

First: contribute directly to sustainable development

It is important to include provisions in international investment facilitation frameworks that directly contribute to sustainable development. Most if not all international investment facilitation frameworks contribute only indirectly to sustainable development as they focus on increasing FDI flows which, in turn, contribute on balance to development. But experts have also put forward a number of additional investment facilitation provisions that directly increase the contribution of FDI to sustainable development. Examples include supplier development programmes to increase the number and capacity of qualified local enterprises that can contract with foreign affiliates as well as supplier databases to help investors identify potential subcontractors. Development, environment and social impact assessments as well as behavioural incentives can be effective tools to enhance the contribution of FDI to sustainable development (Sauvant et al., 2021). Furthermore, we can learn from the experience with other international treaties, such as the TFA, which includes a provision of an “Authorized Economic Operator” that stipulates that importing and exporting companies receive certain trade facilitation benefits if they comply with a set of predefined requirements and supply chain security standards. Inspired by this provision in the TFA, a special category of a “Recognized Sustainable Investor” has been proposed to incentivize investors to invest sustainably. Such recognized investors receive additional benefits if they meet certain predefined, country-specific FDI sustainability characteristics and international corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards (Sauvant and Gabor, 2021). When introducing sustainable development criteria it is important to strike the right balance in order not to discourage foreign investors. The examples above highlight that additional sustainability requirements from foreign investors can be compensated for by offering certain benefits or easier access to local suppliers.

A cooperative approach between home countries and host countries on the one hand, and between host countries and foreign investors on the other hand, could better help countries in achieving their SDGs. This could be done through home and host countries determining certain FDI sustainability characteristics (Sauvant and Mann, 2019). Such characteristics include, among others, local linkages, low carbon footprint, labour rights, supply chain standards, non-involvement in corrupt practices, stakeholder engagement and the development of green strategies. Another key provision to enhance cooperative relations among stakeholders are dispute prevention and management mechanisms. They not only contribute significantly to improving the investment climate of states but also avoid the existing formalized dispute settlement mechanisms (see below).

Responsible business conduct can contribute significantly to strengthening investment’s positive role in sustainable growth, thus contributing to the SDGs. One particular tool that states should adopt in the context of investment facilitation involves sustainability impact assessments: investment facilitation requires a continuing process of reviewing, monitoring and assessing the impact of investments in the territory of a state in order to better adjust and identify which sectors require more facilitation for sustainable development.

Second: focus on conflict prevention and management

WTO members should focus on designing and establishing dispute prevention and management mechanisms for the smooth implementation of the framework while ensuring that investment facilitation provisions are properly insulated from international investment agreements (IIAs). As investment facilitation frameworks may have subject matter overlaps with existing IIAs, it is possible that disputes under investment facilitation frameworks may be submitted to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), which is subject to growing criticism. This could also hurt the exclusive and compulsory jurisdiction of the WTO’s or regional trade agreements’ dispute settlement systems. A proper firewall clause in the framework would help prevent such disputes from being submitted to ISDS, thus insulating the framework from ISDS.

Effective dispute prevention and management mechanisms could avoid the need for international dispute settlement approaches. At the national level, ombudsperson-type mechanisms or broader grievance-management mechanisms should be set up to promptly address investors’ concerns. States should also enhance capacity building to improve their officials’ awareness and knowledge of international obligations they undertake, monitor sensitive sectors that are prone to disputes and set up an early warning system. At the international level, states may consider setting up an intergovernmental communication and cooperation mechanism to improve the coherence of investment facilitation policies, laws and regulations and their implementation. Establishment of a new intergovernmental agency or mechanism to supervise the implementation of the frameworks may also be considered. In case a disagreement occurs between states relating to the frameworks, they should be encouraged to address it through negotiation or in other amicable ways.

Third: learn from experiences from other initiatives such as the TFA

Investment facilitation and trade facilitation share a number of key features. Instead of establishing rigid substantive rules for the liberalization or protection of investment, investment facilitation focuses on improving the implementation of regulatory processes as well as domestic institutions and frameworks. Both define good policy practices for the attraction and retention of FDI and establish cooperative frameworks among governments as well as with investors, in particular by developing countries (Hoekman, 2021). Given these similarities, it is necessary to reflect on key lessons from trade facilitation for investment facilitation initiatives.

One key lesson is that it is important to mobilize an epistemic community that may be needed to define which rules are particularly effective for attracting and retaining investments. While there is no analogue to the World Customs Organisation, as in the context of the TFA, the G20’s TIWG and the international organizations participating in its meetings could form part of a nascent community. A key instrument to mobilize relevant actors at the national level, including national and subnational IPAs, has been the establishment of national trade facilitation committees, an institutional arrangement that could be replicated in the context of investment facilitation. For example, a joint project of the International Trade Centre (ITC) and the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) brings together key actors on investment facilitation among WTO missions in Geneva, policy-makers in capital cities, IPAs, representatives of regional and international organizations and academic experts.2 Another example is the Sustainable Investment Policy and Practice initiative of the World Economic Forum, with country projects in Cambodia, Ghana, India, Kenya and Papua New Guinea.3 Efforts along these lines should be strengthened.

Another key lesson from the TFA is that it is crucial to nurture effective communication between business and government. Business engagement in the TFA negotiations helped to identify specific types of border clearance processes that create uncertainty and high transactions costs, as well as possible solutions. Authorities are not necessarily able to identify where facilitation efforts should be targeted to have the highest impact, or to assess the impacts of measures put in place to facilitate investment. Investors, analogous to traders in the TFA context, are the best placed actors to provide such information, helping governments and the broader stakeholder community to determine where to prioritize efforts to facilitate investment.

Implementation of the TFA is being successfully supported through a Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation. This alliance develops public-private projects at the national and regional levels to implement the TFA and improve trade facilitation. The first projects have been formally evaluated and found to have made a significant difference to speeding up the time and lowering the cost of trade, with benefits well above project costs. For instance, in Colombia, the project led to a 30 per cent decline in physical inspections and, for those goods no longer physically inspected, a reduction in clearance time from two days to three hours (Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation, 2020).

A similar alliance is proposed to support implementation of investment facilitation and generate similar benefits. An Alliance to Enable Action on Sustainable Investment (EASI), or EASI Alliance, would improve cooperation between reform-minded governments, the local and international private sector, expert institutions and donors (WEF, 2021). It would complement existing national and international efforts by drawing on established expertise, reinforcing ministerial and CEO-level commitment, bringing in local, bottom-up knowledge and prioritizing collaborative delivery. Since the private sector is essential to identify impediments to investment, it can help to overcome them. A slight difference between trade and investment facilitation should be mentioned: while trade facilitation mainly focuses on reducing times and costs of trade, investment facilitation should be conceived as not only streamlining procedures and generating more transparent, predictable and cooperative investment frameworks, but also directly contributing to sustainable development.

Launching the EASI Alliance could help reach agreement on a WTO IFF4D agreement. Plans to launch an EASI Alliance could be unveiled at MC12, just as the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation was announced at MC10 in 2015. This could help to produce a high-quality WTO IFF4D, since developing economies would know the EASI Alliance would help contribute to implementation and thus help realize real benefits, and capacity constraints for implementation by developing economies are one of the concerns holding back agreement.

WHAT ROLE FOR THE G20?

Discussions on investment facilitation have been very dynamic from the national to the multilateral level. We recommend initiating a dialogue on key guidelines for investment facilitation discussions:

- design investment facilitation frameworks in a way that they directly contribute to sustainable development;

- incorporate non-adversarial forms of dispute prevention; and

- learn from the experiences of trade facilitation reforms.

The benefits of investment facilitation measures and frameworks will only materialize if they are implemented in practice. This requires both public-private collaboration to identify bottlenecks and blockages to increasing investment flows, as well as firm commitments on substantial technical assistance to address them. It also calls for information on applied policy frameworks and analysis of the effects of investment facilitation efforts that is comparable across countries. Effective monitoring and evaluation require baseline performance indicators and follow-up efforts to track how these change over time. Putting in place a mechanism to develop a set of indicators and compile comparable cross-country information on an annual basis is a public good the G20 can help to provide, by mandating international organizations to undertake such an effort.

The G20 and in particular the TIWG can support investment facilitation efforts during the Italian presidency by initiating a dialogue process with the goal of providing high-level guidance on how investment facilitation frameworks can support sustainable development and recovery. The G20, bringing together the key economic players covering more than 80 per cent of global outward FDI, is in a key position to provide such high-level guidance. Another key feature of the G20 is that it brings together most international organizations active in the investment facilitation space. Furthermore, since the G20’s ecosystem includes the Engagement Groups and Business 20, these could provide key fora to link a G20 initiative on investment facilitation to the private sector.

The G20 should endorse the EASI Alliance to help implement global efforts at investment facilitation. This will help bring awareness to a tangible mechanism to ensure that these efforts actually help increase the flow of FDI and its development impact. Such an endorsement will provide a political signal and confidence that frameworks will not remain on paper but will actually make a difference in practice.

NOTES

1 For their useful comments on previous versions of the paper, we would like to thank Anabel Gonzalez and Lucia Tajoli.

2 See https://www.intracen.org/itc/Investment-Facilitation-for-Development/

3 See https://www.weforum.org/projects/investment

REFERENCES

Berger A, Dadkhah A, Olekseyuk Z (forth coming). Quantifying Investment Facilitation at Country Level: Introducing a new Index, Discussion Paper, Bonn: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE)

Berger A, Ghouri A, Ishikawa T, Sauvant KP, Stephenson M (2018). Towards G20 Guiding Principles on Investment Facilitation for Sustainable Development, T20 Policy Brief, https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/g20-insights-uploads/2019/05/t20-japan-tf8-7-g20-guiding-principles-investment-facilitation.pdf

Evenett S, Fritz J (2021). Advancing Sustainable Development With FDI: Why Policy Must Be Reset, The 27th Global Trade Alert Report, https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/75

G20 (2016). G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking, http://www.g20chn.org/English/Documents/Current/201609/t20160914_3464.html

Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation (2020). Annual Report 2020, Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation, https://www.tradefacilitation.org/content/uploads/2021/04/2020-annual-report-final.pdf

Hoekman B (2021). From trade to investment facilitation: parallels and differences. In Berger A, Sauvant KP (eds.), Investment Facilitation for Development: A Toolkit for Policymakers, Geneva: International Trade Centre, 28-42, https://www.intracen.org/uploadedFiles/intracenorg/Content/Publications/Investment%20Facilitation%20for%20Development_rev.Low-res.pdf

Knight C (2018). The Rise of Subnational IPAs/EDOs, 14 September 2018, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rise-sub-national-ipasedos-chris-knight/

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2018). Mapping of Investment Promotion Agencies in OECD Economies. Paris: OECD, http://www.oecd.org/industry/inv/investment-policy/mapping-of-investment-promotion-agencies-in-OECD-countries.pdf

Sauvant KP, Stephenson M, Hamdani K, Kagan Y (2021). an inventory of concrete measures to facilitate the flow of sustainable FDI: What? Why? How?. In Berger A, Sauvant KP (eds.), Investment Facilitation for Development: A Toolkit for Policymakers, Geneva: International Trade Centre, 43-92, https://www.intracen.org/uploadedFiles/intracenorg/Content/Publications/Investment%20Facilitation%20 for%20Development_rev.Low-res.pdf

Sauvant KP (2019). The Potential value-added of a multilateral framework on investment facilitation for development. In Transnational Dispute Management June 2019, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3399250

Sauvant KP, Gabor E (2021). Facilitating sustainable FDI for sustainable development in a WTO Investment Facilitation Agreement: Four Concrete Proposals. Journal of World Trade, 55:261-286, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3496967

Sauvant KP, Mann H (2019): Making FDI more sustainable: towards an indicative list of FDI sustainability characteristics. Journal of World Investment & Trade 20 (6):916-952, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3509771

Stephenson M, Hamid M, Peter A, Sauvant KP, Serič A, Tajoli L (2020). How the G20 can Advance Sustainable and Digital Investment, T20 Policy Brief, https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/g20-insights-uploads/2020/11/T20_TF1_PB6.pdf

UNCTAD (2021). Investment Trends Monitor, January 2021, Issue 38, Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, https://unctad.org/system/files/ official-document/diaeiainf2021d1_en.pdf

WEF (World Economic Forum) (2021). Launching an Alliance to Enable Action on Sustainable Investment (EASI), Geneva_ World Economic Forum, June 2021. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Launching_an_Alliance_to_Enable_Action_on_Sustainable_Investment_2021.pdf