Establishing international fintech partnerships is recognised as a crucial strategy to promote the development of the fintech sector. Although such partnerships represent a promising opportunity for growth and greater financial inclusion, the asymmetric power dynamics amongst fintech operators internationally leaves fintech operators in the emerging/developing economies reluctant to partner with the well-skilled and resourced fintech giants. The formation of a G20 Fintech Association Forum provides an opportunity to form partnerships on a level playing field. The G20 provides necessary leadership and trust to overcome barriers to collaboration and partnerships, whilst protecting the interests of small-scale fintech operators.

Challenge

In many respects, the limited impact of Fintech in promoting financial inclusion within developing and emerging economies has been due to a limited sharing of knowledge to address common challenges experienced in other economies. Enabling innovations across varied institutional contexts is difficult when there is a lack of a leading role model and there is limited trust between institutions with asymmetric power relations. Therefore, many of the fintech development challenges are knowledge management challenges for sharing and learning within a commercial environment. The question which emerges is whether there is a role for governments to manage competing interests within the financial sector given that fintech intellectual property is a comparative advantage.

Sharing insights and learning from peer institutions (locally and internationally) is essential for the growth and development of the fintech sectors, and contributes to the promotion of financial inclusion in developing and emerging economies. However, financial service providers, who are interested in partnering with foreign financial service providers have various concerns that obfuscate the development of international fintech partnerships. Apart from the fear of the unknown of doing business in a foreign land, there are various risks that the financial service provider must assess before committing to a partnership.

There is a need for an objective framework to underpin fintech partnerships and knowledge sharing agreements across the G20. Such a framework will allow an equal opportunity for all recognised fintech operators in a country to have their needs represented and interests protected when entering into a potential asymmetric partnership. Some of the major concerns of fintech providers about entering into a partnership include:

1) how to effectively overcome a seemingly initial asymmetric partnership by developing a constructive and mutually beneficial relationship.

2) how to enter into a partnership with an international financial service provider with limited knowledge of the local cultural and regulatory contexts.

3) how to ensure that the risks of the partnership, are not transferred to the customers in the form of increased transactional costs or reduced market competition.

Whilst the concerns of financial service providers persists, opportunities for local and international partnerships stagnates. There is a need to also promote local partnerships in a manner that allow local fintech operators an opportunity to develop their capabilities and strengthen their position before they engage in international partnerships.

Given these concerns, governments have a responsibility to their citizens to protect their interests, whilst concomitantly promoting innovation as a means to support the growth and development of their country’s financial sector. This needs to be done in a manner that:

1) highlights the strengths of fintech operators locally

2) prevents unfair competition and monopolistic tendencies within the market and

3) enables the local fintech sector to leverage their collective expertise.

The following proposal identifies a framework for the G20 to support the development of a G20 Fintech Association Forum promoting national and international fintech partnerships.

Proposal

Background

Greater financial inclusion, involving both the access and usage of a broad range of financial products, has been widely recognised as a means to erradicate poverty, and is a strategy for supporting upward social mobility. World Bank researchers contend that greater financial inclusion provides the poor people opportunities to invest in their future and manage their consumption together with financial risks (Demirguc-kunt, Asli.; Klapper, Leora.; Singer, 2017). Within sub-saharan Africa rates of access to financial products have grown substantially in the last decade with countries such as Kenya and South Africa recognised by the World Economimc Forum and the Brookings Institution as some of the most financially inclusive emerging markets in the world (Villasenor, West, & Lewis, 2016 p7). However, the reportedly higher rates of inclusion have not translated into an adequate poverty eradication strategy.

Within Kenya, mobile financial services were introduced in 2007, supported by an enabling legislative framework in 2006 and a rollout of a agent network in 2010. However, despite these efforts over this period, many believe the limited impact of these advances is because the state of transformation is still perceived to be within the “early days” phase, preventing measuring the consequential transformative effects of financial inclusion (Mugo & Kilonzo, 2017). Given the increased rates of access, there is an acceptance of technology but an inability to cross the frontier of sustainable economic impact.

During a similar period in China, the country achieved remarkable success in promoting financial inclusion by managing to scale access to financial services at a rapid rate. In 2007, China accounted for 1% of world-wide financial transactions, and increased this to more than 40% in 2017 (Woetzel et al., 2017). This advance was led by giant internet companies such as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent each supporting multi-industry digital ecosystems. China’s rapid fintech growth has been attributed to protection-oriented policies limiting interference from global incumbents, an innovation enabling environment and continuous learning. With a digitally enabled public, keen to experiment with new products, the country was able to collect substantial datasets informing fintech providers how best to design a range of products suitably configured to the needs and culture of their users (Bai, Jiang, Wang, Chien, & Randall, 2018).

Throughout this period of growth, partnerships between the major fintech players in China has been key to their rapid growth, allowing them to share data, secure joint financing, introduce new products and deepen their understanding of their customer bases. Particularly in China, parternships between internet and financial service providers were found to be mutually beneficial, managing to integrate talent, data and capital into their platforms. Their willingness to share data and recognising the diverse needs of a varied market has contributed to improving product designs appropriate for customers (Desai, 2016; Gorjón, 2018). This openness to partnerships differs from the experiences in Sub-Saharan Africa, where smaller fintech operators are generally eager to partner with a larger institution to gain market-share but thereafter face various challenges in maintaining the partnership due to an imbalance of power (Osborn, 2018). In light of these challenges, traditional financial institutions and fintech entrepreneurs in South Africa have both expressed a fear that their businesses are at risk from partnerships (Price Waterhouse & Coopers, 2017). Given these fears, partnerships are formed hesitantly with incumbent partners choosing to collaborate at first to gain a better insight into their partner’s operating model before committing to invest fully in a partnership.

To date, although this hesitancy remains, financial service stakeholders recognise the opportunities to solve the challenges in the fintech sector through partnerships and have expressed a need to form independent national fintech associations which allow members to collectively benefit from fellow member’s insights, and acting as an interface with other associations both regionally and globally.

Methodology

The Human Sciences Research Council in partnership with Zhejiang University’s Center for Internet Finance and Innovation conducted surveys within Southern and East Africa, as well as within China to gather views of financial service providers who are both interested in and concerned with entering into partnerships between China and the respective African country. The study found that the asymmetric power dynamic between fintech operators across these countries is a cause for concern, despite the potential benefits of partnerships. The challenges when entering into international collaboration agreements are congruent with knowledge management theories applicable to practices and processes for sharing knowledge in international contexts. Considering this alignment, the findings from the survey are supported by a review of literature on the applications of knowledge management strategies within the fintech context. The recommendation for an international Fintech Association Forum was proposed by several of the study participants during follow-up discussions on the results of the survey.

Establishing a G20 Fintech Association Forum

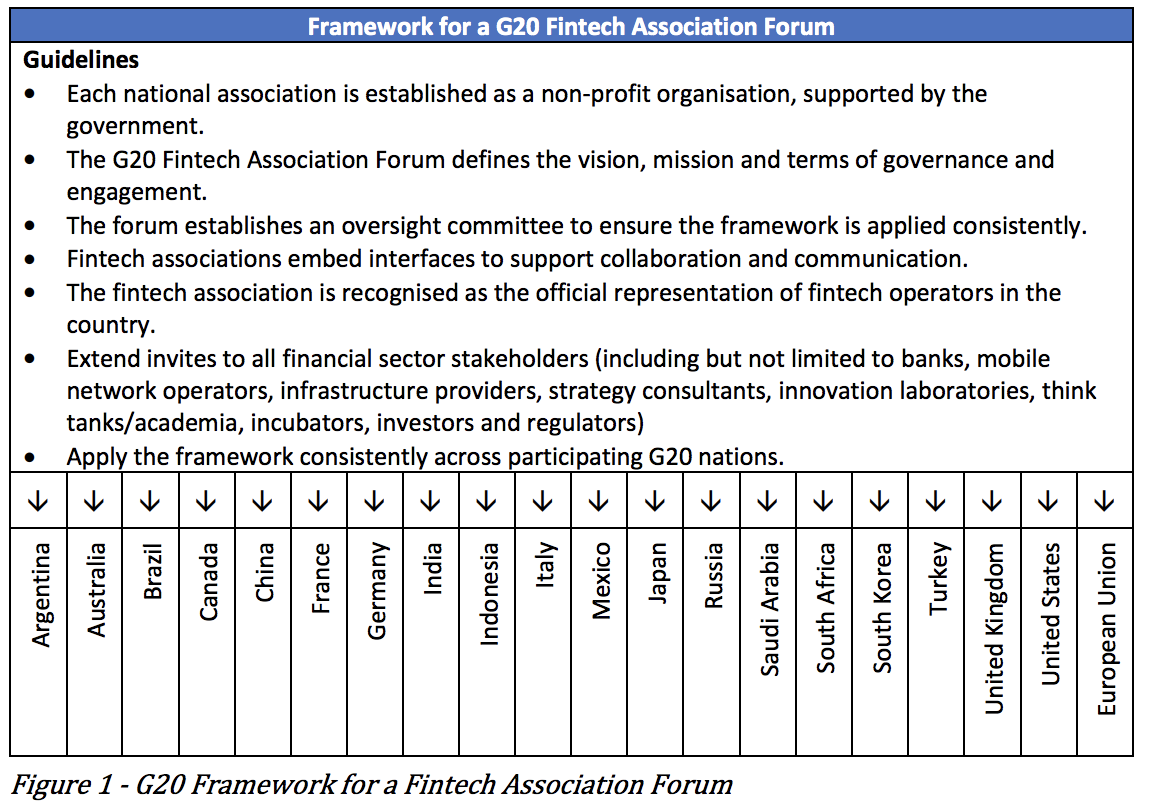

The proposed G20 Fintech Association is a forum that adopts a common construct amongst participating members, defining how participating nations can work together promoting collaboration and partnerships across nations. As a non-profit organsiation which is member driven, the association operates independently although supported by government. The recognition of the forum by the G20 as the official mechanism to engage fintech stakeholders multilaterally, gives the nations’ fintech associations the necessary authority to act on behalf of their country. Each country joining the forum and establishes its own fintech association, champions the cause of fintech in their country and also submits to following the forum’s overarching framework for engagement.

It is important that each nation’s association, whilst following the prescribed rules of engagement, are still allowed to act independently of government direction, while an overarching G20 forum oversight committee reviews whether participating associations follow the agreed terms of engagement. The members of such a committee shall be selected by representatives from each member association. The forum may be funded by the affiliated member associations, who in-turn are funded by their member institutions. The association shall be supported and recognised by the government, but is managed by the association’s members.

The centrality of the G20 internationally, provides a unique position to initiate and coordinate collaboration amongst international stakeholders. For any knowledge sharing arrangement to be successfully implemented, two key factors are required, viz. leadership and trust (Lee, Gillespie, Mann, & Wearing, 2010). These factors provide members of the forum confidence to contribute useful ideas, collaborate, share vulnerabilities openly and discuss strategies for multinational partnerships. In the absence of trust, participating members will conceal information, leading to a breakdown in communication. The central leadership role played by the G20 in the global economy enables it as an ideal vehicle to promote collaboration and knowledge sharing.

In this context, the G20 must provide enabling conditions to support the exploration of new knowledge/new innovations and exploitation of existing knowledge to benefit affiliated associations. These are the essential elements needed for promoting innovation in an international context (Newell, Robertson, Scarborough, & Swan, 2009 pp 213-231). To leverage existing knowledge through partnerships requires that the G20 explicitly define the strategic vision and mission of the forum and the rules of governance and engagement for such a forum. Within a complex and multicultural environment as the G20 nations, a structured approach to managing organisation processes promotes the flow of information and activities in optimal directions, to the benefit of the organisation (Morgan, 2006 p21).

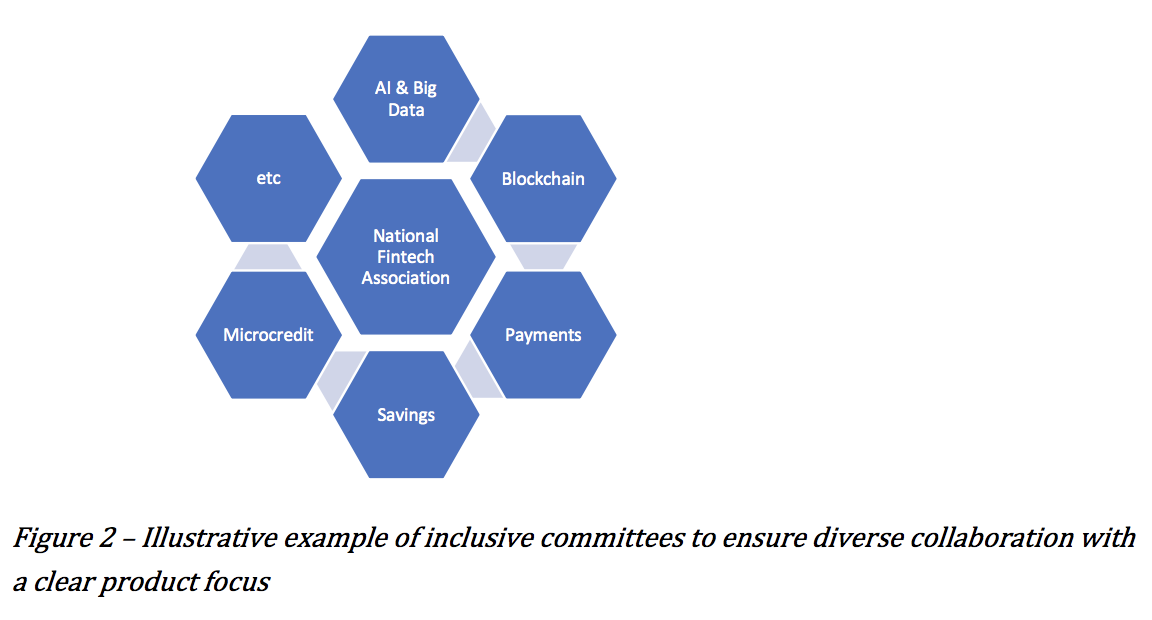

In broad strokes, the forum exists to enable fintech operators to advocate for partnerships, collaborate and share knowledge. The rules of engagement define how countries are represented in a balanced manner and how organisations from these countries participate in the forum. Each association, acting independently of government, manages their membership by inviting relevant financial sector stakeholders. Thereafter, the association may elect a board of directors to determine the association’s unique strategy for national and interntional engagement. In this instance collective leadership is preferable in a networked environment as it is independent of power dynamics and protects the broad interests of the association’s stakeholders (Raelin, 2017). Thereafter, the association may appoint a general manager to run the operational concerns. Overtime, each association can develop a series of committees specialisng on the needs of a particular priority product area.

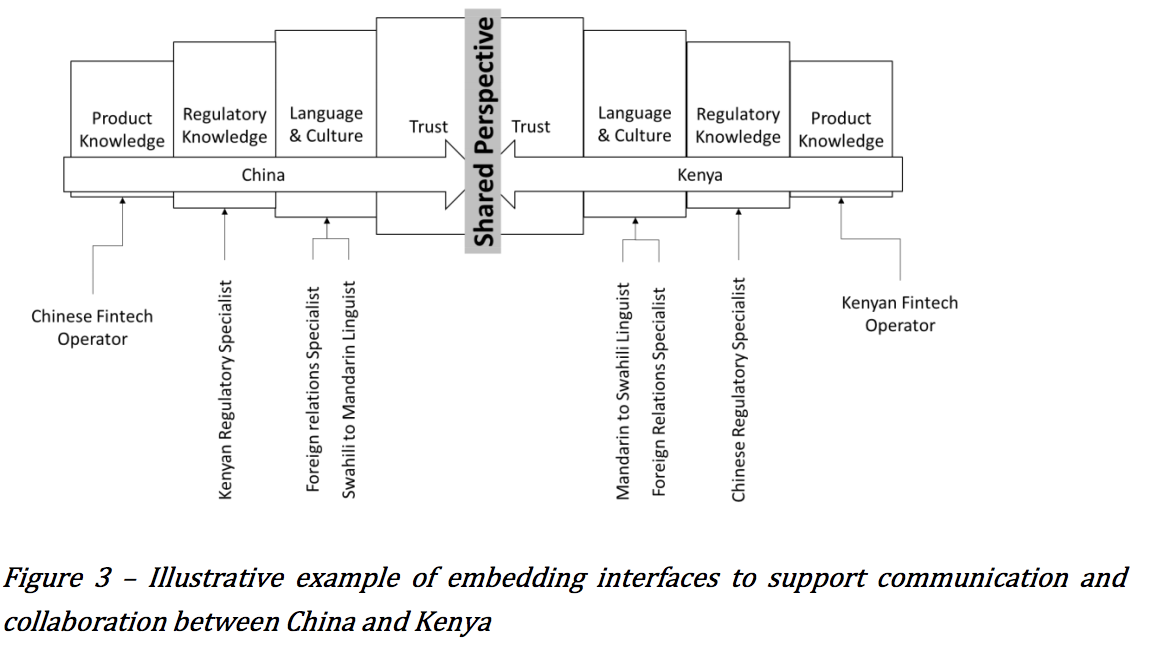

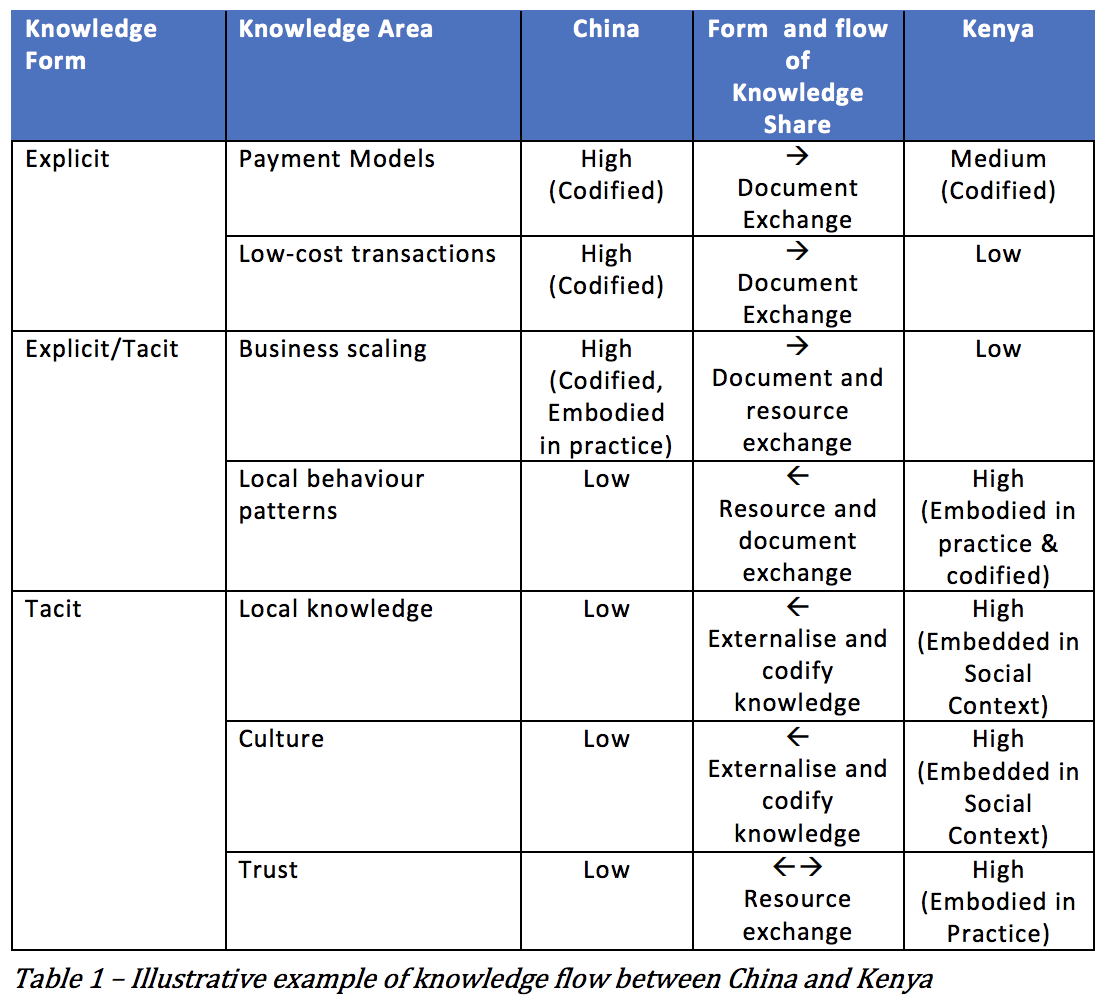

The forum provides the means for fintech associations to share perspectives and develop trust across their respective boundaries. To establish a shared perspective which enables communication, it advised that the fintech associations develop methods to overcome barriers to collaboration such as language, culture and regulation, amongst others. As described in the figure below, this requires appointing sufficient and suitable support resources to act on behalf of the association to support communication, where, for example, they would be able to perform language translation, advise interested product owners about cultural differences and assist in terms of understanding regulatory requirements of the country. The role of such boundary spanning resources create an interface for the respective participants to communicate effectively (Safford, Sawyer, Kocher, Hiers, & Cross, 2017). Acting through a formal forum, with resources aiding communication and collaboration, ultimately boosts trust in the incumbent partner’s competence and by operating through formal and consistent structures, the potential partners are more assured that any partnership entered into, is equally committed to by the incumbent.

Fintech associations drive knowledge sharing

Before entering into international partnerships, fintech stakeholders from SubSaharan African expressed a need to develop local capabilities and maximise their potential locally before entering into an international partnership because they felt it will be unfairly weighted in favour of the foreign incumbent partner.

A strategy for maximising local capabilities is to promote local knowledge sharing, without necessarily entering into a formal partnership. The fintech association provides the platform for existing members to directly collaborate within or across inclusive sub-committees of the association. Further, resources are available to assist in externalising local insights and codifying this content for future consumption. By including boundary spanning resources within the design of the association, the associations and forum is supported in overcoming barriers to collaboration and learning (Du & Pan, 2013).

In studying the Chinese Fintech model it is apparent that China’s rapid growth in Fintech access and usage was driven by sharing data, learning, applying and creating new knowledge in an enabling environment (Mittal & Lloyd, 2016). Through the introduction of National Fintech Association, it is envisaged that fintech operators globally will be supported to have the same opportunity to share insights in a safe environment thereby expanding their reach and making greater strides in promoting financial inclusion.

As described below, when sharing knowledge with an international partner, there is a role for the fintech association to support the manner in which knowledge is shared. Given that knowledge exists in various forms, be-it tacit or explicit or located in someone’s head or repeated in embrained practices conducted by staff, support resources are required to assist in the process of sharing this knowledge. This involves either relocating a resource, getting advice about local processes or receiving assistance in the form of language transaction. Each function is essential when sharing knowledge.

Fintech associations to broker international partnerships

Each national fintech association provides a unified voice for the country’s fintech ecosystem and allows the diverse array of fintech stakeholders to be equally represented. This promotes opportunities to learn from fellow local fintech operators and have the opportunity to engage via formal channels with a peer fintech operator from a foreign country. Nationally representative fintech associations are gaining traction and are active in Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan to name a few (FTAHK, 2017).

The national fintech association provides the means to broker partnerships between interested nations and individual fintech operators. The association protects the interests of individual financial service providers because partnerships are not entered into until the association is assured that a partnership is mutually beneficial. As the fintech association is affiliated to the G20 Fintech Association Forum, the country’s association has recourse to challenge unfair practices and request compensation where necessary.

When two nations wish to enter into a bilateral partnership, the associations act as proxies of the entire sector and determine which members are capable of collaborating based on the needs of the local sector. In this process, the association assesses the peer fintech operator in terms of readiness and feasibility for partnership. If suitable the association is accredited and referred to local operators for possible partnerships. Given varied national contexts and needs of their stakeholders, each association will determine a set of criteria to establish whether and how a fintech partnership can be formed.

With the assistance of resources dedicated to promoting the collective development of the sector, the members of the association are better supported and equipped to enter into a collaborative agreement informed and more aware of any potential risks attributed to a partnership.

Recommendations

1) Establish a G20 Fintech Association Forum underpinned by a framework for the forum, which defines the involvement of government, the terms of governance and engagement in promoting international collaboration.

2) Affiliated national fintech associations are to be recognised and supported by G20 member nations.

3) Affiliated national fintech associations are to follow the guidelines determined by the G20 Fintech Association Forum, ensuring that all national fintech associations operate in a consistent manner.

4) Boundary spanning resources should be appointed by National Fintech Associations to overcome barriers to collaboration.

REFERENCES

• Bai, D., Jiang, R., Wang, T., Chien, J., & Randall, D. (2018). Toward Universal Financial Inclusion in China: Models, Challenges and Global Lessons. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/2933 6/FinancialInclusionChinaP158554.pdf?sequence=9&isAllowed=y

• Demirguc-kunt, Asli.; Klapper, Leora.; Singer, D. (2017). Financial inclusion and inclusive growth A review of recent empirical evidence. Policy Research Working Paper.

• Desai, F. (2016). Why Fintech Is Different In Asia. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/falgunidesai/2016/04/29/asiasfintech-potential/#228e6b1561e5

• Du, W. D., & Pan, S. L. (2013). Boundary Spanning by Design: Toward Aligning Boundary-Spanning Capacity and Strategy in IT Outsourcing. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ENGINEERING MANAGEMENT, 60(1), 59–76. http://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2012.2206114

• FTAHK. (2017). FinTech Association of Hong Kong Partners with FinTech Associations in Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan to Promote Global FinTech. Retrieved February 1, 2019, from https://www.ftahk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/FTAHK_MoUsrelease-26-October-2017.pdf

• Gorjón, S. (2018). The growth of the FinTech industry in China : a singular case. Economic Bulletin, 4(October).

• Lee, P., Gillespie, N., Mann, L., & Wearing, A. (2010). Leadership and trust: Their effect on knowledge sharing and team performance. Management Learning, 41(4), 473–491. http://doi.org/10.1177/1350507610362036

• Mittal, S., & Lloyd, J. (2016). The Rise of FinTech in China. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-the-rise-offintech-in-china/$FILE/ey-the-rise-of-fintech-in-china.pdf

• Morgan, G. (2006). Images of Organisation. (D. Foster, Ed.) (Updated ed). SAGE Publications Ltd.

• Mugo, M., & Kilonzo, E. (2017). Community-levle impacts of Financial Inclusion in Kenya with particular focus on poverty eradication and employment creation. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wpcontent/uploads/sites/22/2017/04/Matu-Mugo-and-Evelyne-KilonzoUN-SDGs-Paper5May2017-Kenya-Financial-Inclusion.pdf

• Newell, S., Robertson, M., Scarborough, H., & Swan, J. (2009). Managing Knowledge, Work and Innovation (2nd Editio). Palgrave Macmillan.

• Osborn, J. (2018). Eight things we learned in China driving Fintech fortune. Retrieved from https://www.financedigitalafrica.org/blog/2018/07/eight-things-welearned-in-china-driving-fintech-fortune/

• Price Waterhouse & Coopers. (2017). Redrawing the lines: FinTech’s growing influence on Financial Services. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/financialservices/assets/pwc-fintech-exec-summary-2017.pdf

• Raelin, J. A. (2017). What Are You Afraid Of: Collective Leadership and its Learning Implications. Management Learning, 49(1). http://doi.org/10.1177/1350507617729974

• Safford, H. D., Sawyer, S. C., Kocher, S. D., Hiers, J. K., & Cross, M. (2017). Linking knowledge to action : the role of boundary spanners in translating ecology. Front Ecol Environ, 15(10), 560–568. http://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1731

• Villasenor, J. D., West, D. M., & Lewis, R. J. (2016). The 2016 Brookings Financial and Digital Inclusion Project Report: Advancing Equitable Financial Ecosystems. Washington DC. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/08/fdip_20160816_project_report.pdf

• Woetzel, J., Seong, J., Wang, K. W., Manyika, J., Chui, M., & Wong, W. (2017). China’s Digital Economy – A leading global force.