The COVID-19 pandemic has led to widespread closures of educational institutions and mass transitions to the Internet, television, and/or radio to facilitate remote learning. However, the wide disparity in learners’ access to the Internet and other technologies at home within and across countries is raising concerns about gaps in learning and learning losses. The safety and well-being of both learners and educators forced to acclimatize to remote education without preparation and support are further concerns. This policy brief proposes a G20 Coalition in Transformative Action for Education to harness G20 expertise and resources in order to widen access to remote education and enhance the quality and safety thereof. It further proposes the timely re-instatement of access to in-person education once local transmission of COVID-19 is suppressed, and the safety of learners and staff in schools and other education settings is ensured.

Challenge

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to widespread closures of educational institutions and a mass transition toward the Internet, television, and/or radio to facilitate remote learning (World Bank 2020c). However, there exists a disparity in learners’ access to the Internet and other technologies across countries, including among members of the Group of Twenty (G20) (International Telecommunication Union 2018, 2020; World Bank 2020b). In general, educators and learners have been poorly prepared for remote and mixed modes of learning[1] (World Bank 2020b). This raises the specter of significant learning losses for some learners (Doyle 2020; Reimers and Schleicher 2020), as well as concerns for the e-safety (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF] 2020a), and for the well-being of participants (World Bank 2020b). The economic shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to also shrink the global economy by 3% in 2020, which would negatively affect “both the demand for and supply of education” (World Bank 2020b, 5). The higher education sector is particularly vulnerable, since public financial support for such institutions is expected to weaken, and international student enrollments and commercial activity on campus are set to decrease (Marinoni, van’t Land, and Jensen 2020).

With no reliable predictions on when the pandemic will end, the onus is on governments in partnership with public and private bodies, non-governmental organizations, and civil society to establish contingency planning that mitigates and manages future risks. The adage “In adversity lies opportunity” directs us to improve our educational systems, offerings, and processes as we move out of the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Bank (2020b, 5) encourages countries to “build back better” and “build toward improved systems and accelerated learning for all students.” The G20 partnership, therefore, needs to consider how best to support the creation of resilient, effective, equitable, and adaptable education systems and processes that can better respond to and mitigate the effects of current and future crises (United Nations 2020a; Reimers and Schleicher 2020). In this regard, provisions to improve access to the technological infrastructures for remote education within and beyond G20 countries are a current necessity. Furthermore, educators, learners, and parents need support and guidance to enable safer and more seamless transitions to remote modes of education during periods that disrupt in-school education. Finally, there is an urgent need for the G20 to explore more sustainable financial and operational models in the event of long-term disruptions to the education sector.

Proposal

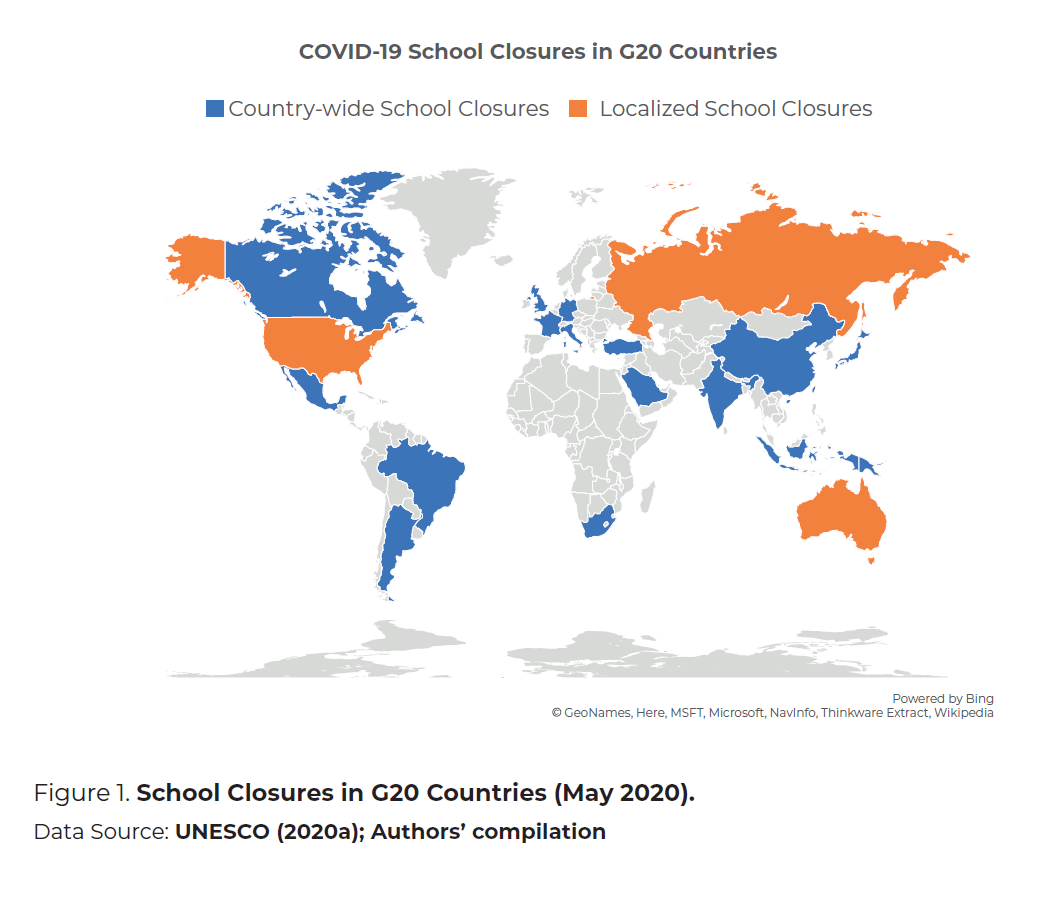

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all formal education, with academic studies disrupted or halted for many students across the globe (World Bank 2020a, 2020b). Most G20 countries[2] have been subject to country-wide school closures affecting 70% or more of school-going children (see Figure 1), with the exceptions of Australia, Russia, and the United States, where localized school closures were enforced (UNESCO 2020a). Overall, more than 1.5 billion learners, constituting 91.3% of the total enrollments at the pre-primary, primary, lower-secondary, and upper-secondary levels of education, across 194 countries were affected by early April (UNESCO 2020a). Ninety-nine percent of all formally enrolled students in tertiary education institutes were affected by the closures (Bassett and Arnhold 2020).

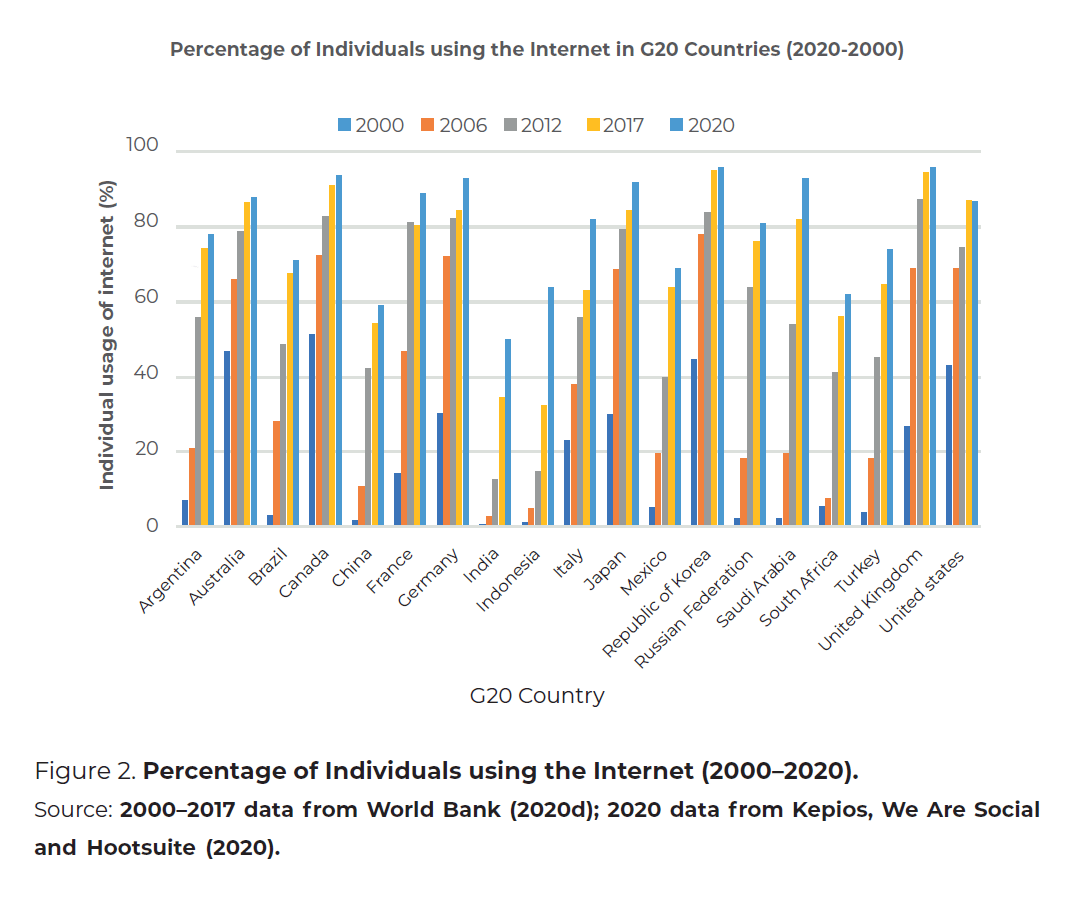

The immediate response of many schools and tertiary education institutions to the closure of physical campuses has been to pivot to distance learning, particularly online learning. Although access to the Internet has greatly increased since 2000, its usage has varied within and across countries, including in the G20 (see Figure 2). At the outset of 2020, the percentage of individual Internet usage varied considerably across G20 countries, with a lower percentage of Internet users (ranging from 50% to 75%) in India, China, South Africa, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, and Turkey, and a much higher percentage of Internet users (ranging from 87% to 96%) in the United States, Australia, France, Japan, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Republic of Korea, and the United Kingdom[3]. The lower percentages of Internet users in India (50%) and China (59%) are a particular concern, since these countries have a large school-aged population of 286 million and 233 million, respectively (UNESCO 2020a). Thus, 280 million children across these countries did not have access to remote learning during school closures.

Of further concern are those countries with a low percentage of households with a computer, as reported by the International Telecommunication Union (2018). In the G20, this includes India (16.5%), Indonesia (19.1%), South Africa (21.9%), Mexico (45.4%), and Brazil (46.3%) (see Table A1, Appendix). The lack of universal access to the Internet or to a computer in the home are significant barriers to education (UNICEF 2020c). These barriers must be removed to enable continuity of learning during transitions to remote and mixed modes of learning during COVID-19 outbreaks.

Target 4.2 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly 2015) seeks to ensure that all children have access to quality early childhood development and care, and pre-primary education. Children who engage with quality “pre-school programmes with a strong educational component” generally reap more benefits than children solely accessing general childcare (Gromada, Richardson, and Rees 2020, 5). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has stymied the realization of these benefits and progress towards achievement of Target 4.2. UNICEF (2020d) estimates that, by July 2020, 40 million children across the world would have missed out on the pre-school year of early childhood education.

Furthermore, child education and care provision during the pandemic has mainly fallen upon parent(s)[4] because of social distancing restrictions. Evidence suggests that many parents have struggled to balance work and family commitments (Gromada, Richardson, and Rees 2020). The vast majority of children up to grade VI (aged 11–12), and those with special or additional needs across all education levels, require sustained encouragement and guidance when engaging with remote education. However, not all parents have the capacity, or resources, to provide this level of support within the home (Doyle 2020). The G20 needs urgently to review structures within the early childhood, primary, and post-primary education sectors to ensure that all learners are appropriately supported in remote learning. Inadequate pre-school education provision, or absence thereof, needs to be addressed as a matter of priority as well.

Similarly, the lack of access to childcare providers and education services during the pandemic has particularly hit frontline workers and those wishing or mandated to return to work-place campuses. As virus outbreaks are controlled, social distancing restrictions can be reduced and school and care settings re-opened. However, there is concern among some parents, staff, and providers about the lack of “back-to-school” preparedness and resourcing of childcare and education centers (Pearcey et al. 2020; Chua et al. 2020). The “new normal” within education and care settings will require infrastructural adaptations and additional human resourcing to implement physical distancing, adhere to health and hygiene regulations, and support the well-being of children and staff. There is an imperative for the G20 to articulate, implement, and appropriately resource structures that enable safe, accessible, and inclusive early childhood, primary, and post-primary education (in-school).

Finally, while recognizing that all education sectors are currently vulnerable, the financial viability of higher education is of particular concern (Bevins et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2020; World Bank 2020a). The G20 needs to take action to support the higher education sector amid the fiscal and financial uncertainties caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Policy Recommendations

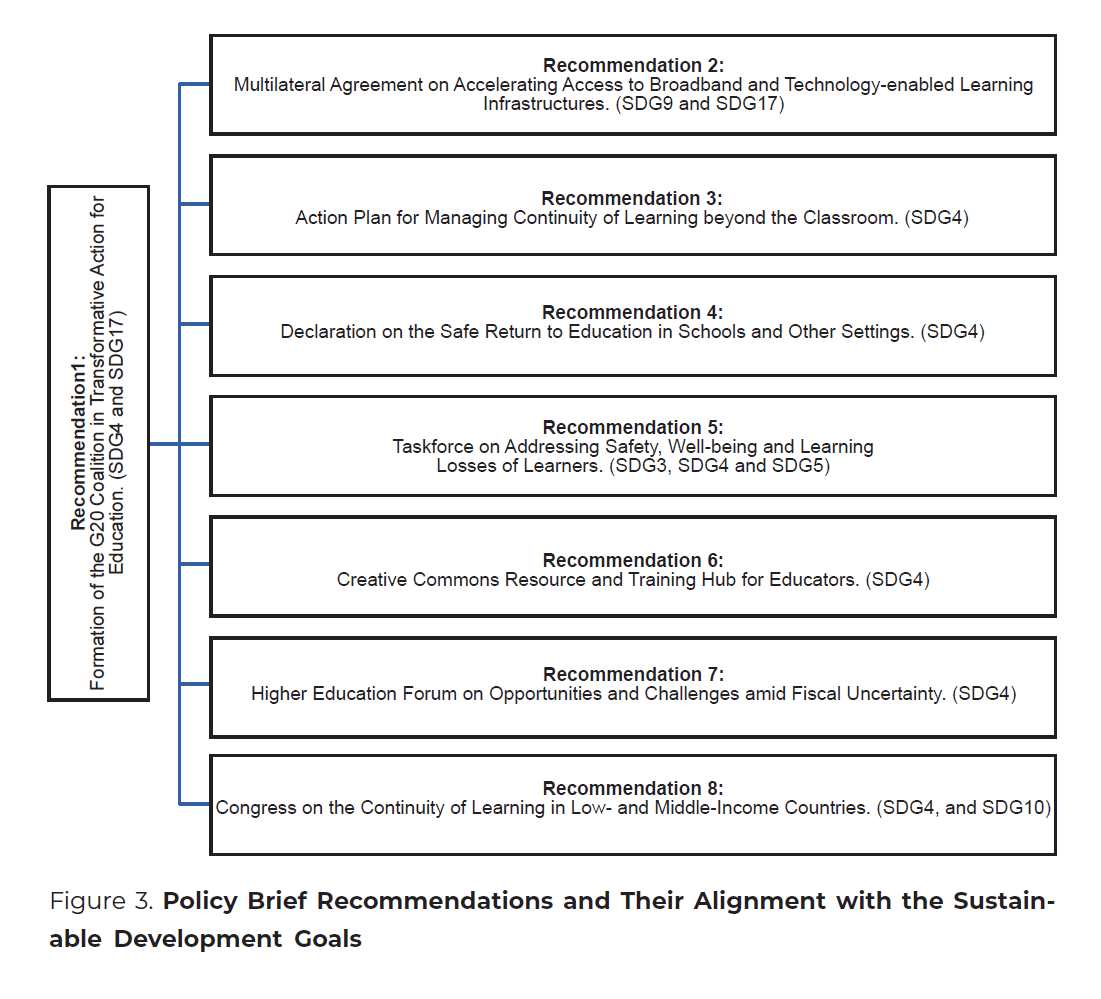

This proposal aims to address the aforementioned issues through a G20 Coalition in Transformative Action for Education that would implement a series of recommended actions. The following recommendations have been inspired by COVID-19 education briefs from organizations including, but not limited to, the United Nations, UNESCO, UNICEF, Education Cannot Wait, and the World Bank. Insights have also been drawn from a review of governmental and agency actions on education during global school closures. Finally, the authors used their own expertise and insights from their substantive experience in working and researching at various levels of education to reach a consensus on recommendations for transformative action in education.

As illustrated in Figure 3, there are eight recommendations to be implemented, and the recommendations align with specific sustainable development goals (SDGs) outlined within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly 2015).

Recommendation 1: Formation of G20 Coalition in Transformative Action for Education

The global recommendation of this policy brief is for the immediate establishment of the G20 Coalition in Transformative Action for Education, which will ensure the continuity of learning within and beyond the COVID-19 crisis. The G20 Coalition will coordinate expertise and resources from across its member countries to streamline responses to education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The G20 Coalition will enable sharing of information on strategies that have successfully addressed inequality of access to broadband, educational technologies, or other infrastructures in remote education. The G20 Coalition will be steered by a group of experts and policymakers in education and related areas. The principles underpinning the G20 Coalition are as follows:

- Multilateral and bilateral cooperation will underpin the work of the G20 Coalition, including engagement with COVID-19 efforts undertaken by global bodies such as the UNESCO Global Education Coalition[5] (UNESCO 2020c).

- Diversity and inclusion will be reflected in the processes of the G20 Coalition, which will seek to enhance the quality of decision-making and guidance through consultation across a range of sectors and agencies.

- Complementary development (as opposed to competitive development) will be prioritized within the G20 Coalition to guard against duplication of efforts within partner countries.

- Quality and agility will underpin emergency actions, committing the G20 Coalition to the provision and deployment of emergency funding schemes in a manner that ensures rapid, high-quality responses to educational needs during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

Recommendation 2: Multilateral Agreement on Accelerating Access to Broadband and Technology-enabled Learning Infrastructures

The second recommendation is for the G20 Coalition to initiate processes that enable a multilateral agreement for accelerating access to broadband and technology-enabled infrastructures in schools, communities, and homes across the G20 countries (UNICEF 2020b; Reimers and Schleicher 2020). Within this agreement, the G20 partnership will commit to finding ways to improve learners’ access to appropriate levels of broadband connectivity and digital technologies or other non-technological resourcing necessary to sustainably support remote modes of education. This can be realized through private investment (World Bank n.d.), public–private partnerships (Lucey and Mitchell 2016), and other innovative means such as negotiating significantly reduced broadband subscriptions rates with Internet service providers. The G20 will commit within this multilateral agreement to liaise with local councils and global bodies such as UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition and Education Cannot Wait.[6] In doing so, the G20 will provide targeted funding and/or access to the Internet and other technologies (UNESCO 2020d) that enable better learning reach within marginalized and vulnerable groups.

Recommendation 3: Action Plan for Managing Continuity of Learning Beyond the Classroom

To counter the on-going disruptions to education, a plan for managing the continuity of learning and assessment is needed (UNICEF 2020b) — ideally one that benefits from the expertise of the G20 partnership. The third recommendation for the G20 Coalition is to articulate an “Action Plan,” with accompanying structures and strategies, for managing the continuity of learning through fully remote and mixed modes of education for the foreseeable future. The G20 Coalition will provide advice, guidance, and resourcing for the following aspects through its Action Plan:

- Specialized accelerated training for pre-service and in-service educators (at all levels on quality teaching, learning, and assessment within fully remote and mixed forms of education, with particular focus on strategies to enable selfdirected learning and collaboration among learners (Selwyn 2020).

- Curation and preparation of online and offline learning content for use during emergency transitions to remote and mixed forms of learning, including the development of online micro-modules to support basic education.

- Review of current assessment frameworks to increase the percentage of formative assessment at all levels of education; otherwise “teachers will be flying blind on learning as they try to support their students remotely” (World Bank 2020b, 6). Because of restricted access to work-place settings during the COVID-19 pandemic, formative assessments for clinical, work-based, and practitioner placements will need to be re-cast to include alternative assessment work to replace the on-site assessment visits by external supervisors or examiners.

- Training on maintaining academic integrity within assessments for remote education, including responsible and ethical online assessment practice (Watson and Sottile 2010).

- Review of curricular frameworks to examine opportunities for the introduction of micro-credentials for coursework that will be recognized at local, national, and/or G20 levels.

- Review of structures to integrate mental and emotional support for educators, parents, and care-givers (Education Cannot Wait 2020).

- Review of pre-service and in-service teacher education programs to integrate suitable training for and examination of the educators’ capacity to design, deliver, and assess within remote education provision contexts.

- Review of regulations pertaining to ongoing teacher evaluations and whole school evaluations to include examination of remote modes of learning and assessment.

- Development of a parental advice brief for remote education. This will explain the parental roles and responsibilities during the facilitation of remote learning, including advice on the broad domains of “care, stimulation and play” for the early childhood context as called upon by UNICEF (Gromada, Richardson, and Rees 2020, 9)

Recommendation 4: Declaration on the Safe Return to Education in Schools and Other Settings

The recent Global Education Monitoring Report highlights the importance of implementing policies that actively strive to address equity of access and inclusion in education (UNESCO 2020b). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted access to in-school delivery of early childhood, primary, and post-primary education within G20 countries (UNESCO 2020a). Learners from marginalized and/or socioeconomic disadvantaged groups face greater difficulty in transitioning to remote learning because of poor, or no, access to technology or broadband at home (Reimers and Schleicher 2020; Vegas 2020). In addition, in the absence of appropriate adult guidance and support in the home, the quality of the remote learning experiences is less effective than in-person education facilitated by a teacher. Inadequate parental support for remote learning particularly affects younger children up to grade level VI, and children with special or additional needs across all levels of education, with serious consequences for their social, emotional, and cognitive development (UNICEF 2020d). Therefore, there is an imperative for the G20 to articulate, implement, and appropriately resource structures that enable safe, accessible, and inclusive early childhood, primary, and post-primary education services. In this regard, the G20 Coalition will undertake the following actions:

- Formulate a G20 Declaration acknowledging early childhood, primary, and post-primary education as “vital services” that will strive to remain open insofar as it is possible, allowing for in-person education in school settings when the local transmission of COVID-19 has been suppressed (United Nations 2020b). Schools and other settings will be (re)closed during outbreaks in a particular institution or surrounding area, or for other reasons such as a government-mandated regional or national lockdown. The G20 Declaration will refer to the G20’s commitment to provide the necessary resources to enable, as far as possible, in-school facilitation by teachers of early childhood, primary, and post-primary education during the pandemic. These resources include the human and financial capital for regular testing of children and staff for the COVID-19, adaptations to implement physical distancing and hygiene regulations, and supporting the safety, health, and well-being of all children and staff. The G20 Declaration will further prioritize access to in-person education for younger children up to grade level VI, as well as for children with special or additional needs, throughout the pandemic.

- Establish a high-level forum to review the governance, costs, and educational quality of pre-school programs. This forum will reflect the G20’s commitment to maintain access to high-quality pre-school programs within and beyond the pandemic. It will include representatives from sectors including education, housing, and employment, and will seek holistic solutions that address the wider familial and societal issues that affect the (non)enrollment of children in pre-school programs (Williams 2020).

Recommendation 5: Taskforce on Addressing Safety, Well-being, and Learning Losses of Learners

With distance learning, a new normal has emerged wherein parents operate as in loco teachers within the home. However, differing levels and quality of support from parents will inevitably lead to learning losses for those already experiencing a disadvantage, thus widening the existing opportunity gaps for learners and increasing educational inequalities (Cooper et al. 1996; Doyle 2020; Reimers and Schleicher 2020; Vegas 2020). School closures also mean that higher numbers of learners have had to engage with online technologies within remote offerings of education. However, in the absence of appropriate digital literacy, the latter presents additional challenges in ensuring the e-safety and privacy of learners. The World Bank (2020b) further raises concerns about the mental health and well-being of learners in enforced isolation, particularly girls and young women experiencing hardships within the home. The disruption to the school nutrition programs on which “some 368 million children worldwide rely” is of particular concern (World Bank 2020b, 6). To counter these issues, the G20 Coalition will convene a Taskforce to provide guidance on information, funding, and dedicated training that will enhance the safety and well-being of learners and redress any learning losses. This Taskforce will comprise educational and health experts who will report to the G20 Coalition on the following actions:

- Through the assistance of the Youth Engagement Group to the G20, the Taskforce will ascertain the range of supports available and any additional help required to enhance the safety and well-being of young people within crisis periods, and in the cultural transitions toward remote and mixed modes of education.

- The Taskforce will collate practical advice and guidance for parents and caregivers on how to effectively manage their health and anxieties, and that of their children. It will further provide information on how to support quality learning while addressing basic needs during crisis periods (United Nation 2020a; Education Cannot Wait 2020).

- The Taskforce will review the training available to enhance the digital literacies of learners and further conduct a meta-analysis of literature to assess whether regulations in the G20 countries adequately protect the privacy and safety of children online (United Nations 2020a; UNICEF 2020a).

- The Taskforce will conduct a review of initiatives proven to reduce or remove barriers to education for girls and young women, such as the demands of care provision within the home and insufficient home or school access to learning resources (Education Cannot Wait 2020).

- The Taskforce will collate information on financial support and other resources that can be accessed to address gaps in learning caused by COVID-19 crisis, with a particular focus on aiding vulnerable and marginalized groups (Education Cannot Wait 2020).

Recommendation 6: Creative Commons Resource and Training Hub for Educators

The G20 Coalition will establish structures for an online platform that can be used by educators across the G20 partnership for resource sharing and training. This “hub” will operate under the principles of creative commons and universal design, ensuring that the materials developed and shared within this platform are of a high quality and can be made freely available to educators. To address quality assurance and encourage innovation within the hub, the following actions will be undertaken:

- The G20 Coalition will commit to establishing an expert group that will provide advice on sourcing high-quality online educational resources that align with state and curricula requirements in key disciplinary areas at differing levels of education.

- The G20 Coalition will seek to identify and fund access to high-quality, culturally responsive online modules that can accelerate pre-service and in-service teacher training on digital literacies and digital learning.

- The G20 Coalition will seek to explore the potential for bi-lateral covenant(s) across partner G20 countries to provide for skills-sharing, open-access modules, and/or localization of content.

- The G20 Coalition will provide funding to map and research more agile models of fully remote and mixed modes of learning, as well as accelerated and disruptive learning models. This research work will underpin the efforts to recover learning losses, accelerate learning, and/ or counter the dominance of face-to-face instruction within mainstream models of education provision.

Recommendation 7: Higher Education Forum on Opportunities and Challenges amid Fiscal and Financial Uncertainties

The higher education sector makes significant contributions through education, innovation, and research to economies and societies at national and global levels. However, the higher education sector is facing unprecedented financial challenges owing to the COVID-19 pandemic (Marinoni, van’t Land, and Jensen 2020). In terms of the latter, higher-education institutes in most countries have had to reduce or curtail commercial activities on campus during the pandemic, and travel restrictions have negatively affected international enrollments (Marinoni, van’t Land, and Jensen 2020). There is a real and present danger that governments’ fiscal uncertainty will lead to financing cuts for publicly funded institutes. Without an appropriately funded higher education sector, there will be significant losses in the intellectual outputs necessary for future economic and societal developments. Therefore, the G20 Coalition will organize and host a “Higher Education Forum” for leaders of higher education institutions and associations across the G20 partnership. The objectives of this forum will be to

- Affirm support of the G20 partnerships for the higher education sector;

- Facilitate opportunities for collaborative research and innovation on the COVID-19, and other global challenges articulated within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; and

- Identify new sources of funding and sustainable financial models for the higher education sector in expectation of substantial losses of income from reduced (international) student enrollments and curtailment of commercial activities.

Recommendation 8: Congress on the Continuity of Learning in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

In lower-income countries, persistent issues of inadequate or no social protection services, lack of funded childcare, and a dearth of tuition-free pre-school programs have for many years severely affected children’s education and their familial economic circumstances (UNICEF 2020d). National or local school closures during the pandemic have further reduced children’s access to education in both low- and middle-income countries (UNICEF 2020d). Furthermore, the broadcast media (radio and television) being used to deliver education in many of these countries cannot support interactive learning, and as a result, the learning experiences are typically of a lesser quality than those offered through online or in-person education (Vegas 2020). Therefore, only a minority of children in lower-income countries have been able to access or meaningfully engage in quality learning at a distance. Without guidance and support to enable continuity in the provision of quality education in such countries, “a much higher percentage of children are at risk of devastating physical, socioemotional, and cognitive consequences over the entire course of their lives” (Yoshikawa et al. 2020, 188). These ramifications include stagnation or even regression in children’s development, particularly for those under the age of 5 years, in these countries.

The G20 governments have implemented measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 within their jurisdictions alongside strategies to ensure the continuity of critical services such as healthcare and education. These learnings could be particularly beneficial for low- and middle-income countries requiring evidence-based knowledge on successful and unsuccessful strategies vis-à-vis remote education. Therefore, the final recommendation is for the G20 Coalition to host a “Congress” for enabling the continuity of quality education. This Congress would include representatives from governmental and non-governmental organizations from low-income, middle-income, and G20 countries. It will identify sustainable funding models and resources for both inschool and remote modes of education for low- and middle-income countries (United Nations 2020b). It will further enable the sharing of experiences and reveal the potential for synergies to empower quality education provisions (such as country-level partnerships to provide access to broadband and technology-enabled infrastructures) across low-income, middle-income, and G20 countries.

Conclusion

The primary focus of this policy brief is on the distance-learning provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Remote modes of education are important in supporting the continuity of education during school closures. However, the lack of access to digital technologies and inadequate parental support for home-learning has left millions of learners disadvantaged. Remote education cannot be a panacea for education in times of crises. Instead, the re-opening of schools must be set in motion as soon as the local transmission of COVID-19 is under-control, as “getting students back into schools and learning institutions as safely as possible must be a top priority” according to the United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres (2020). The alternative would be “a generational catastrophe” (Guterres 2020), where hard-won gains in expanded access to quality education, particularly in regions of deprivation within and beyond the G20 partnership, are likely to be stalled or reversed as a result of ongoing disruptions to education.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Bassett, Roberta Malee, and Nina Arnhold. 2020. “COVID-19’s Immense Impact on

Equity in Tertiary Education.” World Bank Blogs, April 30, 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/covid-19s-immense-impact-equity-tertiary-education.

Bevins, Frankki, Jake Bryant, Charag Krishnan, and Jonathan Law. 2020. “Coronavirus:

How Should US Higher Education Plan for an Uncertain Future.” McKinsey &

Company. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/Coronavirus%20How%20should%20US%20higher%20education%20plan%20for%20an%20uncertain%20future/Coronavirus-How-should-US-higher-education-plan-for-an-uncertain-future-final.pdf.

Chua, Kao-Ping, Melissa DeJonckheere, Sarah L. Reeves, Alison C. Tribble, and Lisa

A. Prosser. 2020. “Plans for School Attendance and Support for COVID-19 Risk Mitigation

Measures.” Accessed August 2, 2020. https://ihpi.umich.edu/sites/default/files/2020-06/plans%20for%20school%20attendance%20and%20support%20for%20risk%20mitigation%20measures%20among%20parents%20and%20guardians_final.pdf.

Cooper, Harris, Barbara Nye, Kelly Charlton, James Lindsay, and Scott Greathouse.

1996. “The Effects of Summer Vacation on Achievement Test Scores: A Narrative and

Meta-Analytic Review.” Review of Educational Research 66, no. 3 (September): 227–

68. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066003227.

Doyle, Orla. 2020. “COVID_19: Exacerbating Educational Inequalities?” Accessed May

22, 2020. http://publicpolicy.ie/downloads/papers/2020/COVID_19_Exacerbating_Educational_Inequalities.pdf.

Education Cannot Wait. 2020. “COVID-19 and Education in Emergencies.” Accessed

May 19, 2020. https://www.educationcannotwait.org/covid-19.

Gromada, Anna, Dominic Richardson and Gwyther Rees. 2020. “Childcare in a Global

Crisis: The Impact of COVID-19 on Work and Family Life.” Innocenti Research Brief

2020-18. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. Accessed July 27,

2020. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IRB-2020-18-childcare-in-a-globalcrisis-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-work-and-family-life.pdf.

Guterres, António. 2020. “António Guterres (Secretary-General) On The Launch of

The Policy Brief on Education and COVID-19.” Accessed August 4, 2020. http://webtv.un.org/watch/antónio-guterres-un-secretary-general-on-the-launch-of-the-policybrief-on-education-and-covid-19/6177761587001/?term=.

Marinoni, Giorgio, Hilligje van’t Land, and Trine Jensen. 2020. “The Impact Of

COVID-19 on Higher Education Around The World.” IAU Global Survey Report. Paris:

International Association of Universities. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf.

International Telecommunication Union. 2018. “Measuring the Information Society

Report. Volume 2. 2018.” Accessed June 4, 2020. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/publications/misr2018/MISR-2018-Vol-2-E.pdf.

International Telecommunication Union. 2020. “Statistics.” Accessed June 4, 2020.

https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx.

Kepios, We Are Social and Hootsuite. 2020. “Digital 2020. Global Digital Yearbook.”

Accessed June 4, 2020. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview.

Kim, Hayoung, Charag Krishnan, Jonathan Law, and Ted Rounsaville. 2020. “COVID-19

and US Higher Education Enrollment: Preparing Leaders for Fall.” McKinsey & Company.

Accessed August 7, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/COVID%2019%20and%20US%20higher%20education%20enrollment%20Preparing%20leaders%20for%20fall/COVID-19-and-US-higher-education-enrollment-Preparing-leaders-for-fall_F.pdf.

Lucey, Patrick, and Christopher Mitchell. 2016. “Successful Strategies for Broadband

Public-Private Partnerships.” Institute for Local Self Reliance. Accessed May 19, 2020.

https://ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2016/07/PPP-Report-2016.pdf.

Pearcey, Samantha, Adrienne Shum, Polly Waite, and Cathy Creswell. 2020. “Report

03: Parents/ Carers Report on Their Own and Their Children’s Concerns about Children

Attending School.” Accessed August 2, 2020. https://emergingminds.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Co-SPACE-report03_School-concerns_23-05-20.pdf.

Reimers, Fernando M., and Andreas Schleicher. 2020. “A Framework to Guide an Education

Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020.” OECD. Accessed May 22, 2020.

https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=126_126988-t63lxosohs&title=A-frameworkto-guide-an-education-response-to-the-Covid-19-Pandemic-of-2020.

Selwyn, Neil. 2020. “Back to School … for Now? It Makes Sense to Plan for More

Remote Learning.” Lens, May 22, 2020. https://lens.monash.edu/@neil-selwyn/2020/05/22/1380501/back-to-school-for-now-we-should-plan-for-more-remotelearning.

United Nations. 2020a. “Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Children.” Accessed

May 25, 2020. https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/160420_Covid_Children_Policy_Brief.pdf.

United Nations. 2020b. “Policy Brief: Education During COVID-19 and Beyond.” Accessed:

August 4, 2020. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf.

United Nations Children’s Fund. 2020a. “COVID-19 and its Implications for Protecting

Children Online.” Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.unicef.org/media/67396/file/COVID-19%20and%20Its%20Implications%20for%20Protecting%20Children%20Online.pdf.

United Nations Children’s Fund. 2020b. “Framework for Reopening Schools.” Accessed

May 29, 2020. https://www.unicef.org/media/68366/file/Framework-for-reopening-schools-2020.pdf.

United Nations Children’s Fund. 2020c. “How Covid-19 is Changing the World: A Statistical

Perspective.” Accessed May 29, 2020. https://data.unicef.org/resources/howcovid-19-is-changing-the-world-a-statistical-perspective.

United Nations Children’s Fund. 2020d. “40 Million Children Miss Out on Early Education

in Critical Pre-school Year due to COVID_19.” Press Release. Accessed: July 27,

2020. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/40-million-children-miss-out-early-education-critical-pre-school-year-due-covid-19.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2020a. “Education:

From Disruption to Recovery: COVID-19 Impact on Education.” Accessed June 10,

2020. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2020b. “Global Education

Monitoring Report 2020. Inclusion and Education: All Means All.” Accessed

July 25, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718?fbclid=IwAR-2L8j0jjrRBoLGFDf65VEjdGnt_nTMtHOT1yb-ZFco_Z57Iobr8HO5-WXI.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2020c. “Global Education

Coalition. #LearningNeverStops. COVID-19 Education Response.” Accessed

June 8, 2020. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2020d. “Global

Education Coalition Facilitates Free Internet Access for Distance Education.” Accessed

May 29, 2020. https://en.unesco.org/news/global-education-coalition-facilitates-free-internet-access-distance-education-several.

United Nations General Assembly. 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda

for Sustainable Development.” A/RES/70/1. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E.

Vegas, Emiliana. 2020. “School Closures, Government Responses, and Learning Inequality

Around the World During COVID-19.” Accessed May 24, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/school-closures-government-responses-and-learning-inequality-around-the-world-during-covid-19.

Watson, George and James Sottile. 2010. “Cheating in the Digital Age: Do Students

Cheat More in Online Courses?” Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration

13, no. 1 (Spring). Accessed August 7, 2020. https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring131/watson131.pdf.

Williams, David. 2020. “COVID-19 Special Edition: Creating Communities of Opportunity.”

The Brain Architects Podcast, April 23, 2020. https://content.blubrry.com/the_brain_architects/COVID_Williams_042320_mixdown_FINAL.mp3.

World Bank. 2020a. “The COVID-19 Crisis Response: Supporting Tertiary Education

for Continuity, Adaptation, and Innovation.” Accessed May 19, 2020. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/621991586463915490/WB-Tertiary-Ed-and-Covid-19-Crisis-forpublic-use-April-9.pdf.

World Bank. 2020b. “The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses.”

Accessed May 20, 2020. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33696/148198.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

World Bank. 2020c. “World Bank Education and COVID-19.” Accessed May 24, 2020.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2020/03/24/world-bank-educationand-covid-19.

World Bank. 2020d. “Individuals using the Internet (% of Population).” Accessed June

3, 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/it.net.user.zs.

World Bank. n.d. “Connecting for Inclusion: Broadband Access for All.” Accessed May

21, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/digitaldevelopment/brief/connecting-for-inclusion-broadband-access-for-all.

Yoshikawa, Hirokazu, Alice J. Wuermli, Pia Rebello Britto, Benard Dreyer, James F.

Leckman, Stephen J. Lye, Liliana Angelica Ponguta, et al. 2020. “Effects of the Global

Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic on Early Childhood Development: Short- and

Long-Term Risks and Mitigating Program and Policy Actions.” Journal of Pediatrics

223 (August): 188–193. Accessed August 6, 2020. https://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(20)30606-5/fulltext.

Appendix

[1] . Mixed modes of learning include both in-person education and remote education.

[2] . The G20 countries are the 19 separate nation states of the G20 partnership, but do not include the European Union

[3] . See https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-yearbook

[4] . The term “parent(s)” is used in this policy brief as an overarching term that is representative of any person(s) who has (have) responsibility for the upbringing and well-being of a child.

[5] . UNESCO Global Education Coalition; see https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition.

[6] . Education Cannot Wait is a fund used to support comprehensive education programs for children and youth affected by conflicts, natural disasters, and displacement; see https://www.educationcannotwait.org.