With 17 goals and 169 targets, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are expected to be achieved around eight years before the deadline. To meet the SDGs target by 2030, it will take between US$5 trillion and $7 trillion per year (UNDP n.d.). However, the current level of investment by governments, development agencies, and other players is insufficient to accomplish these ambitious goals by 2030. The annual financing gap in developing nations is over $2.5 trillion (UNDP, n.d.).

To close the financing gap, private sectors could play an important role in achieving the SDGs by mobilising just 7.76 percent of global assets under management per year, equivalent to $6 trillion (UNDP, n.d.). Currently, many enterprises have been launched and constructed with the main objective of improving social and environmental wellbeing. One of the potential ways to finance SDGs is to encourage and boost impact investing. Impact investing is an important contributor to the SDGs as it enables private capital to address social challenges.

This policy brief helps to explain the difficulties in attracting impact investors, particularly to developing countries, to invest in SDG-aligned sustainable projects and shed some light on the opportunities to boost investors’ commitment to manage and measure impact.

Challenge

Impact investment is a type of investment strategy that aims not only for financial return but also to create a positive and measurable social or environmental impact (Sarmento and Herman, 2020). In other words, impact investment is when investors put their capital into companies to seek results for the world without sacrificing performance. Global Impact Investing Network (2019) formulated four core characteristics of impact investing, which include: intentionality, investment with return expectations, range of return expectations and asset classes and impact measurement.

Impact investing is not a new type of financing (Gutterman, 2021). It has been an advanced development of sustainable investing that started in the 1970s and used the screening process to avoid issues related to the environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria. BNP Paribas (2018) also suggests that impact investing is also referred to as social finance, where the investments will be invested into several projects that have social issues and address issues related to social and economic problems.

Considering the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework, for instance, reducing poverty, increasing gender equality, providing access to clean and affordable energy and creating more sustainable cities and communities, impact investing is an investment style that is perfectly aligned with these indicators as it can unlock private capital to address these issues. While many investors have been making impact investments for decades, for example, as of the end of 2019, the Global Impact Investing Network (2020) estimated the impact investing market size at around $715 billion, managed by over 1,720 entities, many other investors are still bullish about impact investing’s prospects and anticipate larger sizes and efficiency in the future. Despite its perfect scheme to achieve the SGDs and build a better world, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has identified three underlying issues on galvanising impact investing:

- Insights and data on investment opportunities and risks are scarce. In developing countries, investors and businesses (both domestic and international) typically have little or no knowledge of potential SDG-focused private-sector investments or how to link existing investments with local SDG goals. Echoing findings from UNDP, more than half of the respondents in the Global Impact Investing Network Annual Impact Investor Survey in 2020 stated that impact measurement management practice is a significant challenge for impact investing. Suitable exit options are also a major hindrance in impact investing, for example on how to manage the risks of business failure or change of targeted impact (Schiff and Dithrich, 2018);

- Capacity and network limitations. Despite increased interest in and momentum toward SDG-enabling investments, many developing countries lack the necessary mechanisms to implement them. There is also a lack of knowledge about how sustainable investments may aid financial success. Ormiston et al. (2015) suggested that the entire impact investment process needs a combination of financial experts with programmatic experts in the targeted impact, which requires an improvement or a complete transformation in current resources’ knowledge and skills;

- High policy and regulatory risks in least-developed and crisis-affected nations can be caused by uncertain political contexts and weak or fledgling domestic private sectors and capital markets. For example, how fiduciary duties and the legitimacy of taking environmental or social considerations into account when choosing investments, for instance, have been the subject of a heated dispute in the United States (International Finance Corporation, 2021).

Apart from the aforementioned challenges, investors may find it challenging to identify which ideas would work (i.e., making a profit as well as having an impact). While this may be because investors have not done rigorous research into the expected impacts of the ideas or businesses that they will put their money into, the complicated process of finding the right business could probably be caused by survivorship bias. For example, if there are 100 impact investment ideas and 70 of them underperform compared with the benchmark whereas 30 of them outperformed the benchmark by pure chance, the media coverage would mostly come from the 30 successful investments. Based on the MagnifyMoney survey of more than 1,100 US consumers in 2021, most individual investors, 67 percent of the respondents, believe that they have an obligation to invest in firms that have a positive impact on the world. While more than half of retail investors, around 51 percent of the respondents, say they avoid certain stocks because of moral or ethical concerns about the company’s business practices, 32 percent of them actively invest in firms that they would be embarrassed about others knowing, suggesting that a return is still the main driver for some investors. This evidence suggests that more investors are attracted to invest in areas that will have positive benefits (impact investing). Nonetheless, some other investors still value a project that is deemed to be important purely from its economic returns.

Proposal

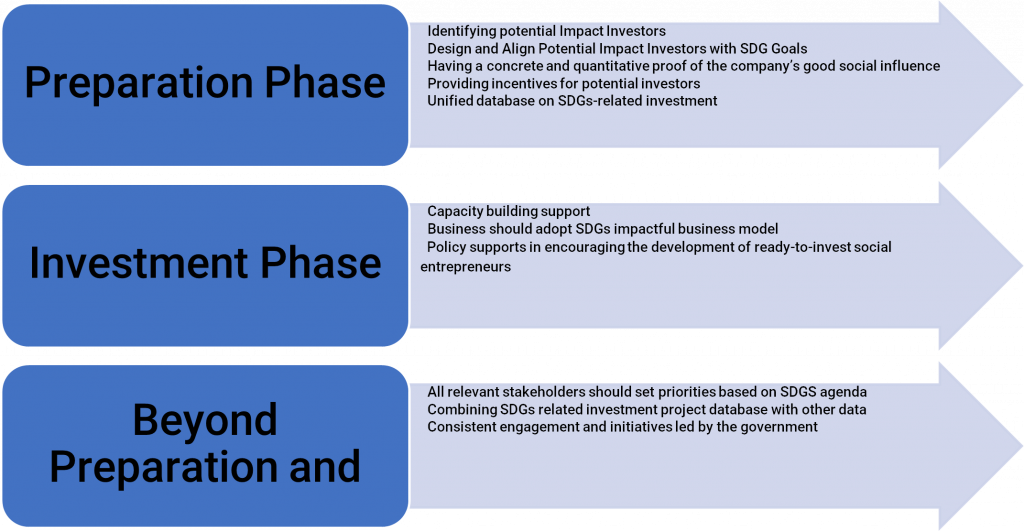

To have more impact investors shift from intent to action and direct more investors to use their capital to achieve the SDGs, there are several strategies that can be organised into two stages. The first stage is the preparation phase, and the second stage is the investment phase. Different strategies are needed during these two periods. Moreover, further policies are needed beyond these two periods to ensure that the policy can be done in a sustainable way. The strategies can be summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proposal for Adopting Impact Investing Program

Stage 1: Preparation phase

Identifying potential impact investors will be the first important aspect during the pre-investment period. Because it is impossible to generate an impact investing policy without identifying what are the characteristics of potential impact investors. Mar Cormac et al. (2020) suggest that there are three types of impact investors.

- Impact-first or impact only investors. This investor is usually a charitable foundation that prioritises impact over financial returns.

- Impact and return investors. This investor tends to place equal priority between impact and financial returns

- Return first investors. This investor focuses on market-rate financial returns but also wants to see the benefit of their investments.

The ability to identify these impact investors may be helpful because it can help related key stakeholders who are the potential investors that need to be approached in order to match the need for any particular investments. [1]

For potential impact investors, the initial preparation of the investments is to clearly define and align their goals with the SDGs. By aligning their goals with the well-established SDGs, it is easier for investors to measure the intended impact of investments. Rockefeller Philanthrophy Advisors (2017) suggest that impact investors explore five key considerations: Why, What, How, When, and Who? before making an official investment. This will also explain what will impact investors should do before being involved in impact investing.

- Why? Impact investors should ask themselves why they are interested in impact investing. Answers may vary from being interested in the impacts it creates, to combine their investment and philanthropy agenda, or trying to have financial performance together with impacts;

- What? The second question that impact investors should ask themselves is what kind of changes they want to create using impact investments. There may be major issues, such as poverty, health, education and climate change all of which are related to the SDGs, or particular issues that investors believe in. In addition to the issue, investors should also consider geographical area, demographics, as well as the type of businesses they want to invest in;

- How? This consideration focuses on how the progress of investment will and at what level should the progress be assessed. Impact investors should have a mechanism for analysing both the financial and social aspects of their investments. The level of measurement for social impact can be at society, community, beneficiary, or investment while the level of measurement for financial return could be a portfolio, asset class, fund, or investment.

- When? There are two questions that investors should have an answer to, the desired period for the impacts to take place and the desired period for the financial return to become reality. It should be noted that the financial return timeline is usually shorter than the impact timeline.

- Who? The last question to be addressed is whom to involve in the investments. Investors may want to work closely with other organisations or work directly with beneficiaries, depending on their preferences.

With increasing interest in socially responsible investments, the starting point for businesses is to have concrete and quantitative proof of the company’s good social influence.

Investors are becoming more keen on discriminating between “greenwash” firms and those that create a beneficial social effect; thus, transparency in this area is becoming increasingly vital. This proof may also attract more firms to switch their business model to attract impact investors. First and foremost, companies should be clear on what they want, how they will achieve it, and how to measure the progress. The Plastic Bank, a for-profit social enterprise founded and based in Vancouver, Canada, is an example of an enterprise that is confronting an environmental issue front-on and quantifying it for investors. The firm is shifting the public image of plastic consumption and allowing individuals living in poverty to earn money while helping the environment by assigning a monetary value to plastic garbage. More than 2,000 plastic collectors have been trained because of this project, and over 3 million kilograms of plastic have been recycled. For investors who seek confirmation that the company they support is making a difference, a boosted economy and large waste reduction are accessible measures;

- Government can influence impact investment directly or indirectly: directly through mandate, for example, green building mandates in large American cities have spurred the development of sustainable property investment strategies. Indirectly through investment subsidy or capacity building.

- The government may attract impact investors by increasing the incentives for them to invest in the country by reducing barriers to investing, improving the business climate, and showing commitment to achieving SDGs. This can also be done by regularly updating and informing the policy that is relevant for impact investors. For instance, when it comes to impact investing, a wide range of tax incentives is typically available to investors residing in the United Kingdom, sometimes as an extra incentive to the good target returns and helpful larger goals impact investments strive to achieve. Naturally, encouraging potential early-stage enterprises to create creative, disruptive, and even revolutionary technologies, which frequently convert into impact investments, is in the government’s best interests. As a result, tax-advantaged investment possibilities are frequently used to close the deficit.

- To address the issue of insights and data on SDG-related investments, the government of each country could develop a database on potential impact investment projects that need funding from private investors. Implementing agencies could be government and other related stakeholders that are responsible for achieving SDGs so that there would be no need to create a new agency. The responsible agencies of each country should also coordinate closely with the ministry of finance or related ministries of the respective country to decide which SDG-related project should be financed by impact investors. This way, government stakeholders can act as a matchmaker between investors and businesses. The database should be publicly available and provide reliable, standardised and comparable data on potential impact investment projects. This way, local or foreign investors will only need to access the database when they are interested in investing in a country.[2]

Stage 2: Investment phase

For the second period, several policies are also important to ensure that the plan that has been initiated can be translated into an increase in the number of investments. Below are several policies that can be adopted during the investment period.

Impact investors could provide capacity-building support, especially for developing nations, either pre- or post-investment. This is to prepare businesses to be investment-ready as well as to increase awareness that businesses have an equally important role in achieving the SDGs. Investors can collaborate with non-government actors, such as academics or other businesses, to provide capacity training to ensure that business activities will stay relevant to SDG targets, businesses understand the challenges in approaching the SDGs and how to act on them.

Apart from publishing sustainability reports, businesses should adopt an SDG-impactful business model. Companies with purpose-driven “impact business models” can create environmental and social value through restorative operating procedures, products and services that help people contribute to the SDGs, inclusive employment practices and other constructive endeavors.

Impact investing requires policies that encourage the development of a pipeline of ready-to-invest social entrepreneurs. It could also be fostered by legislation, such as tax incentives. For example, in 2007, the Republic of Korea passed the Social Enterprise Promotion Act, which provides business services, discounted rentals and lower taxes to social companies. In addition, Thailand’s Social Enterprise Promotion Act exempts corporations that form social enterprises from paying taxes. At the same time, Malaysia’s Social Enterprise Blueprint includes several policy initiatives, including the inclusion of social entrepreneurship courses in national education systems. A study by UNSECAP (2018) suggests that this program has made a positive impact on communities in need, across different beneficiary groups. Even though in some cases, there is still a problem in understanding the proper business model to boost investments.

Stage 3: Beyond preparation and investment

Not only before and during the investment period but policies beyond the pre-investment and investment periods are also needed. Below are several aspects that need to be considered outside these two periods. The most important policy in this period is the evaluation and assessment of existing investment projects. Governments will need to strike a balance between social services provided by the public sector and those in which the private sector is involved. Thus, specific evaluation with clear performance criteria will be paramount.

Of the 17 SDGs, countries, investors and businesses set priorities based on their priority agendas. Using machine learning based on 100 out of 158 voluntary national reviews (VNRs) of the first High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) cycle (2016 – 2019), the UN (2019) found that SDG 17 on global partnership attracted the most attention from countries, followed by SDG 13 on climate change. SDG 10 on inequality received the lowest attention. However, from the same report, it was found that attention to each SDG varied over time. Although it is understandable for stakeholders to pay more attention to their priority agendas, achieving all SDGs is equally important, therefore all relevant stakeholders are encouraged to address each SDG to achieve the 2030 Agenda.

Understanding that governments’ priorities can influence private sector decisions and investors’ behavior, governments could send a signal to the public on SDG priorities, for example through policies and regulation, which in turn encourages the private sector to tap into the prioritised areas (Tomasko et al., 2021)). The governments could also regularly include progress made by private sectors towards SDGs such that they can balance between efforts made by the public and private.

After countries develop a database of potential SDG-related investment projects, this database can be combined such that it will create a global database of all investment projects. The UN could take the lead to make this database as comprehensive as possible. This way, information on impact investments is available worldwide through a single database. Cross-country collaboration will play an important role in this stage. The further strategy will be to merge data on investment opportunities once each country has been able to develop a database for the SDG projects. By doing so potential investors will be able to identify where probable investment will be needed. This collaboration will be most likely to support and benefit developing countries because the pool for potential investors will be expanded.

With limited fiscal capacity, local governments can engage with impact investors to provide public goods or build what the community needs. Building affordable housing units, investing in community-based social entrepreneurs and supporting environmental actions with economic benefits are all examples of impact investments at the local level. Impact investing allows governments to use external money to accomplish local goals and priorities, drive development and governance capacity, and transfer innovation risk.

Relevance to G20 and why it matters

With only a few years to before the deadline, SDGs require no less than a global effort to achieve. One way to close the SDGs financing gap is through impact investment, which involves the private sector aligning their businesses with sustainable development and putting their capital into socially or environmentally impactful projects. Although deemed as an ideal model, there are several challenges that keep impact investors from realising their investment plans. Governments, investors and businesses should work together to resolve the issues.

Comprising the world’s major economies that account for 80 percent of the world’s gross domestic product, 75 percent of global trade, and 60 percent of the population, the G20 leaders should reaffirm their commitment to the 2030 Agenda and pledge to implement the SDGs in their own nations, global policy and international collaboration. At the operational level, the G20 should concentrate its efforts on areas where its actions have significant global significance and/or competitive advantage.

From this policy brief, there are two general directions for the policy recommendation. The first direction is to ensure that the adoption of impact investing will be inclusive for all countries. The second direction is to explore the opportunities of boosting the adoption of impact investing. The policy recommendation can be divided into: 1) Supra-national level, and 2) country level. Specifically, the recommendations are the following:

- Supra-national level policies for G20 countries

- Making impact investing the core strategy to finance SDGs-related expenditure

- Ensuring the commitment from all G20 countries to enhance the use of impact investing

- Increasing the awareness of the importance of alternative financing schemes, especially from the private sector

- Cross-country collaboration, especially related to the unified database related to the potential impact of investing.

- Country level: Policies to boost the adoption of impact investing

- Building a better ecosystem to facilitate potential impact investors

- Providing solid regulation frameworks that will assure the activities are protected by law

- Encouraging potential investors and firms to start attracting impact investing, especially for SDG programs.

Our policy recommendations may help to solve the potential issues and challenges that may affect the implementation of impact investing. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that impact investing is not the only policy that needs to be adopted. Other policies such as increasing fiscal capacity, improving tax policy and building a better business environment will be pivotal for the achievement of the SDG targets.

References

BNP Paribas. 2018. Sustainable Finance. https://group.bnpparibas/en/news/sustainable-finance-about. Accessed April 25, 2022.

UNDP. n.d. SDG Impact: Investment Solutions for Global Impact. UNDP.

Global Impact Investing Network. 2019. thegiin.org. Accessed April 24, 2022. https://thegiin.org/assets/Core percent20Characteristics_webfile.pdf.

Gutterman, A.S., 2021. Sustainable finance and impact investing. Business Expert Press.

International Finance Corporation. (2021). Investing for Impact: The Global Impact Investing Market 2020. World Bank.

Ormiston, J., Charlton, K., Donald, M. S., & Seymour, R. G. (2015). Overcoming the challenges of impact investing: Insights from leading investors. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 352-378.

Rockefeller Philanthrophy Advisors. 2017. www.rockpa.org. Accessed April 24, 2022. https://www.rockpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/RPA_PRM_Impact_Investing_Strategy_Action_WEB.pdf.

Sarmento, E.D.M. and Herman, R.P. eds., 2020. Global Handbook of Impact Investing: Solving Global Problems Via Smarter Capital Markets Towards A More Sustainable Society. John Wiley & Sons.

Schiff, H., & Dithrich, H. (2018). Lasting impact: The need for responsible exits. Global Impact Investing Network.

Tomasko, L., Theodos, B., Eldridge, M., & Park, J. (2021). Strategies for Advancing Impact Investing through Public Policy.

UN. 2019. “un.org.” Accessed April 24, 2022. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/Note-SDGs-VNRs.pdf.

UNESCAP. 2018. The State of Social Enterprise in Malaysia 2018. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/MSES-2018_Final percent20 percent28low-res percent29.pdf

- There are four characteristics of impact investors: intentionality, investment with return expectations, range of return expectations and asset classes and impact measurement. Investors with all four characteristics can be classified as impact investors. ↑

- There has been designated government SDG bodies, for example the SDGs Promotion Headquarters in Japan at the prime minister’s office, the SDGs Dashboard Indonesia by the Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning. These institutions should coordinate with the respective ministry of finance (or related ministries) in terms of how much funding is needed to achieve SDGs, how much should be financed by the government, and how much should be funded by non-governments. ↑