Structural changes in the world economy have altered the way we think about the nexus between trade and growth. In particular, the rise of the services economy and the digital revolution have rocked the world of trade policy-making in ways that are not nearly sufficiently reflected yet in international economic policy forums like the G20. Therefore, this policy brief urges G20 policy-makers to pay greater attention to trade in services and its crucial role in achieving the G20 objectives. Strong, sustainable and inclusive growth will not be achieved without due consideration of services.

Challenge

Ten years after the 2009 Pittsburgh Summit, key items of the G20’s Strong, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth (SSIG) agenda remain unfulfilled. Major objectives of that agenda have stalled, as progress towards more balanced, sustainable and inclusive growth remains elusive (IMF, 2018).

Services have revolutionized the trade landscape

Meanwhile, structural changes in the world economy have altered the way we think about the nexus between trade and growth. While industrial development has played a key role in export-led development trajectories in the past, the modern globalised economy offers much broader, often overlooked possibilities. In particular, the rise of global value chains and the emergence of trade in services have challenged long-held tenets about international trade and its way of driving economic progress. ICT-enabled services in particular offer potential for export diversification that defy the logic of traditional paradigms by relying purely on electronic cross-border delivery, making it accessible even to countries with underdeveloped physical trade infrastructure (eg. Roy, 2017)

In recent years, global exports in manufactured goods as a percentage of GDP have plateaued and even declined by 1.2 percentage points between 2007 and 2017, whereas trade in services has increased its share in GDP (McKinsey, 2019). Most of the growth in services trade is in high value-added and highproductivity sectors such as in ICT and various business services. The services sector is now the dominant destination of FDI flows accounting for roughly two thirds of the global FDI stock, up from less than 50% in 1990 (Roy, 2019).

Policies do not take sufficient account of these revolutions

Against the backdrop of mounting international trade and investment tensions and of calls by WTO members to “de-escalate the situation” (WTO, 2018a), this Policy Brief will argue that policy-makers need to pay greater attention to trade in services and its crucial role in achieving the G20 objectives. Strong, sustainable and inclusive growth will not be achieved without due consideration of services. The need to focus more on trade in services will become increasingly important in the near future as a result of technological changes – notably automation, additive manufacturing, internet of things, machine learning and artificial intelligence applications. The so-called Globalization 4.0 will have major impacts, both positive and negative, on national labor markets and services jobs in particular, a sector that has hitherto been relatively spared from the forces of globalization (Baldwin, 2019). Neglect of services in the design of trade and investment policies would imply a significant loss of growth and development opportunities.

G20 Economies have a particularly high stake in services trade

This policy brief is directed to policy-makers in the G20, a grouping that comprises the world’s leading services traders and accounts for roughly 80% of global services trade and investment. (WTO, 2018b). G20 economies are predominantly service economies. The sector employs 68% of the G20 workforce, and 79% of female employment (2). Services further contribute three fifths (59%) of aggregate G20 output (3). Even relatively small improvements in services trade policy can be expected to translate into sizeable economic gains for G20 countries and their citizens (IMF, 2018).

Proposal

G20 policy-makers need to make trade and investment in services a more central pillar of policy formulation, consonant with the dominant role played by services in modern economies. We recommend the following steps.

Send a clear signal recognizing the importance of services trade for sustainable, balanced and inclusive growth.

The inclusion of dedicated discussions on services trade within the G20 Trade and Investment Working Group agenda is needed to raise the prominence of the topic at a time of mounting trade policy turbulence.

Services constitute a large and growing share of global trade

Services, including the vast array delivered online, represent the new frontier of global trade and investment governance. Their role in international trade and investment flows has been systematically underappreciated. New datasets measuring trade in value-added terms reveal that services represent close to half of world trade, a much larger share than previously thought (Miroudot and Cadestin, 2017). For G20 countries, this number increases to over 50% (WTO/OECD, 2018).

The rising share of services in total trade is also the result of major structural changes occurring in the very fabric of economic activity in the digital era, intertwining goods and services trade and investment more than ever. The socalled “servicification” of manufacturing captures the tendency of manufacturing firms to procure, both at home and abroad, more services inputs than before, and to sell and export more services as integrated or accompanying components of their merchandise exports (e.g. Kommerskollegium, 2012). More broadly, servicification reflects that value creation in all economic activity is shifting towards upstream segments as inputs “embodied” during the production process (e.g. R&D, design, and professional expertise) and to downstream activities “embedded” at the point of merchandise sale (e.g.financing, training, maintenance, repair and other after-sales services). Such shifts have prompted the emergence of new business models at the interface of goods and services production (Stephenson, 2017).

Services trade is key to productivity, inclusiveness and diversification

As G20 countries’ productivity growth remains sluggish, recognizing the role of servicification and services trade for performance and productivity for all firms should be a priority for policy-makers eager to achieve sustainable growth. Recent studies have found that the effects of increased services trade are not confined to the services sector, but have important positive knock-on effects on other sectors of the economy (see eg. Arnold et al.,2015, Crozet & Milet, 2017, and Beverelli et al., 2017).

Realization of a range of sustainability and inclusiveness objectives depends crucially on bolstering the performance of services sectors and improving access to specific services, for which trade and investment can play a key role (Fiorini and Hoekman, 2018). Telecommunications, transport, financial, health, education and environmental services are examples of services that are essential to improving lives and opportunities, through connecting people and markets and improving human capital. The services sector is by far the largest driver of job creation in G20 countries, a trend on the increase with servicification (Schwarzer, 2015). As the predominant source of global female employment, services hold considerable potential for more inclusive growth patterns (Ngai and Petrongolo, 2017).

Finally, expanding the service economy and boosting trade and investment in the sector may be an important pillar of economic diversification strategies – notably for countries with high commodity dependence – and may contribute to the reduction of global imbalances. Recent discussions on current account surpluses and deficits revolve almost entirely around the goods trade balance. While goods traded do embed services, the predominant focus on merchandise trade flows and especially bilateral goods trade balances paints only a partial, distorted, picture. External balances in services often mitigate the trends observed in goods trade, and expanding services trade according to comparative advantage may contribute to reducing overall external balances in the medium-term (IMF, 2018). As such, the services sector can provide a cushion to economic downturns, as has been witnessed during the last recession, when countries with a larger proportion of their exports in services experienced a lesser reduction in trade than did those with a higher proportion of their exports in manufacturing / agriculture (eg Borchert and Mattoo, 2009, and Ariu, 2016).

“Audit” national services trade and investment policies and regulations as a foundation for concerted G20 action

Services are increasingly part of trade agreements…

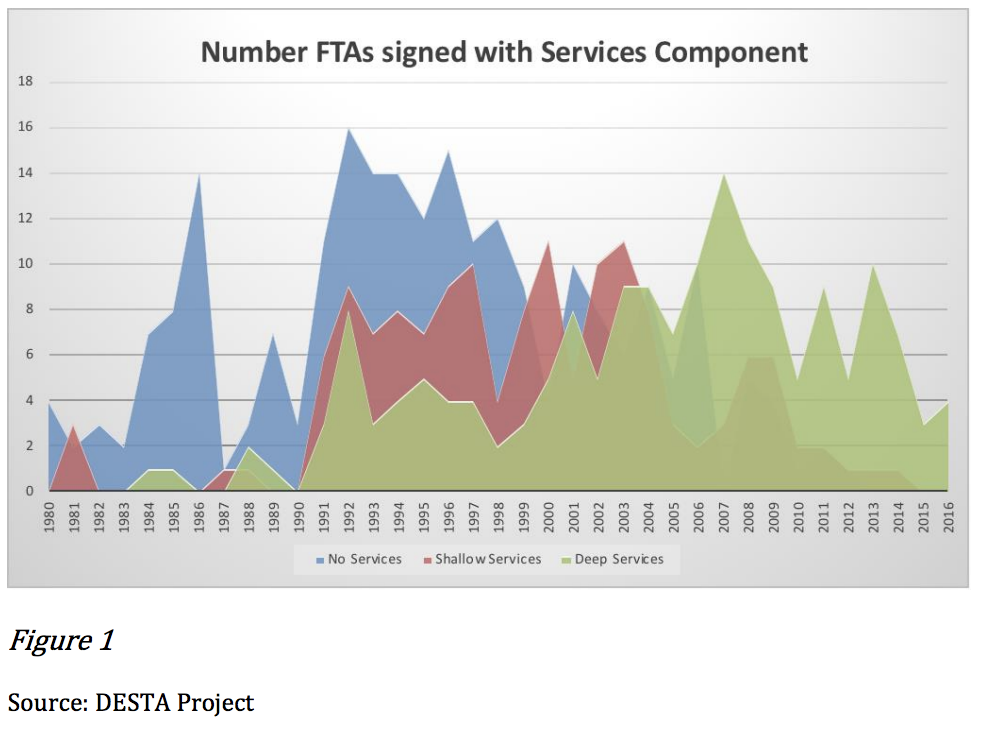

Over the past ten years, 77% of all signed preferential trade agreements have included provisions on trade and investment in services, up from only 16% in the 1990s. There is an increasing tendency towards incorporating provisions on services in free trade agreements (see Figure 1).

At the same time, services negotiations meet with increasing public resistance. Points of criticism include allegedly insufficient carve-outs for public services such as health and education, as well as alleged pressures placed on governments to open sensitive areas, such as energy, transport and financial services to heightened foreign competition. Controversy around privacy and market power in the context of the digital economy are further cases in point.

… but barriers remain pervasive and very high.

Compared to barriers impeding goods trade, obstacles to trade and investment in services remain pervasive. Such obstacles are also often more complex, harder to quantify and protectionist elements may at times be difficult to distinguish from regulation enacted in pursuit of legitimate public policy goals. The ongoing “Fourth Industrial Revolution”, epitomized by technological disruption and the rise of the digital economy, adds another layer of urgency to the need to address services-related issues internationally and to update the global rule-book governing trade and investment in the sector set out in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) (4).

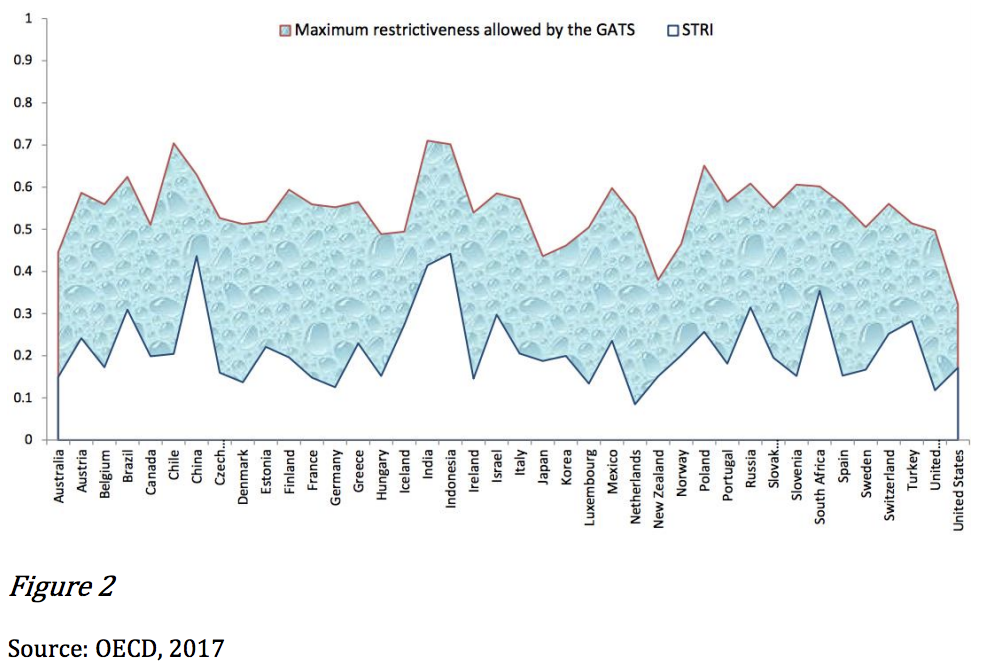

Even though the GATS contains an explicit mandate to negotiate further rules and commitments on services, the varied interests of an increasingly diverse WTO membership have proven to be a major obstacle to discussions that resumed in 2000 without yet producing tangible outcomes. Consequently, a large discrepancy exists between the level of services trade and investment commitments made under the GATS and the actual level of policy openness captured by the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) across countries (see Figure 2) (5).

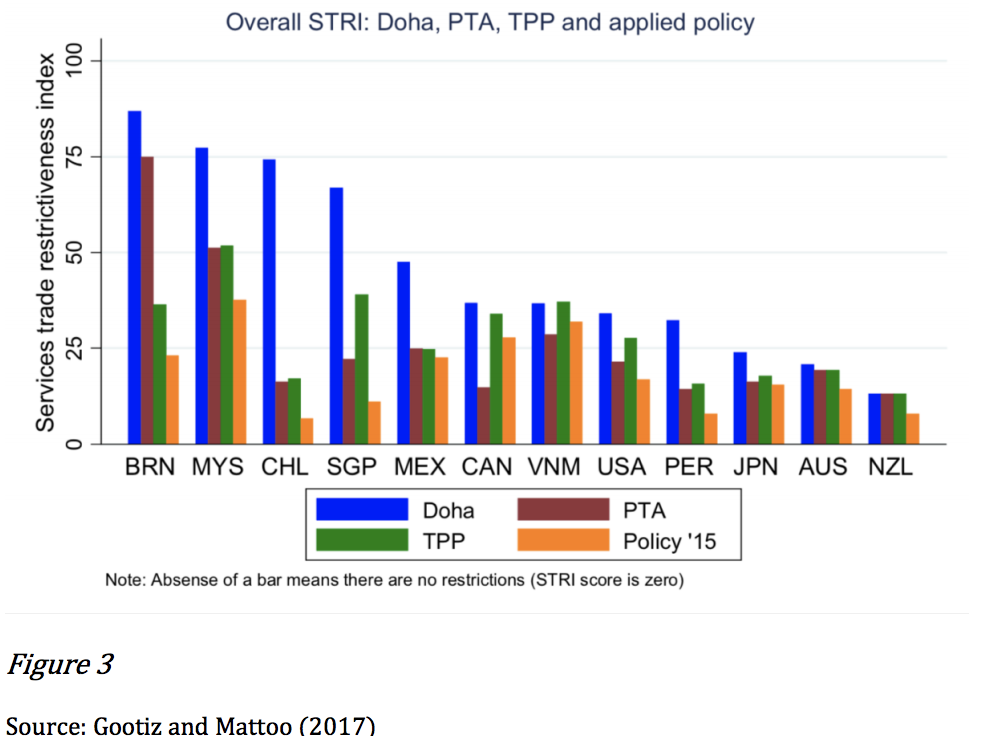

The discrepancy between bound services trade and investment commitments and applied policy is a general feature of services trade both under the WTO GATS and in preferential trade agreements (PTAs). Figure 3 compares four different services trade restrictiveness benchmarks across former TPP countries – which include all CPTPP countries plus the US which has withdrawn from TPP (6). The TPP – and now the CPTPP – is widely hailed to be the most progressive trade agreement in terms of services policy

The first bar (in blue) depicts the latest multilateral benchmark represented by the offers of the now defunct Doha Round, which some countries have designated to be the minimum level of ambition for a possible future Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA). The brown and green bars represent aggregate policy levels for their most progressive PTA and the TPP deal respectively, whereas the orange bar denotes the actual level of applied services policy as of 2015. A tendency towards progressive alignment between international commitments and applied policy is certainly discernible, suggesting that the real current value of PTAs, including the CPTPP, is in enhancing transparency and certainty by reducing the gap with applied policy, irrespective of any significant overall improvements in terms of market access. This interpretation is corroborated by recent research on the benefits of reducing policy uncertainty for trade (Handley and Limão (2017). Lamprecht and Miroudot (forthcoming) estimate that going from the level of commitments bound in GATS to the average level in PTAs is associated with a significant positive impact on trade in the range of 8% to 12% depending on the sector. For developing countries, the trade-enhancing effect of PTAs that cover services is almost double the effect of PTAs that only cover goods (Lee, 2018), confirming the importance of services trade for development.

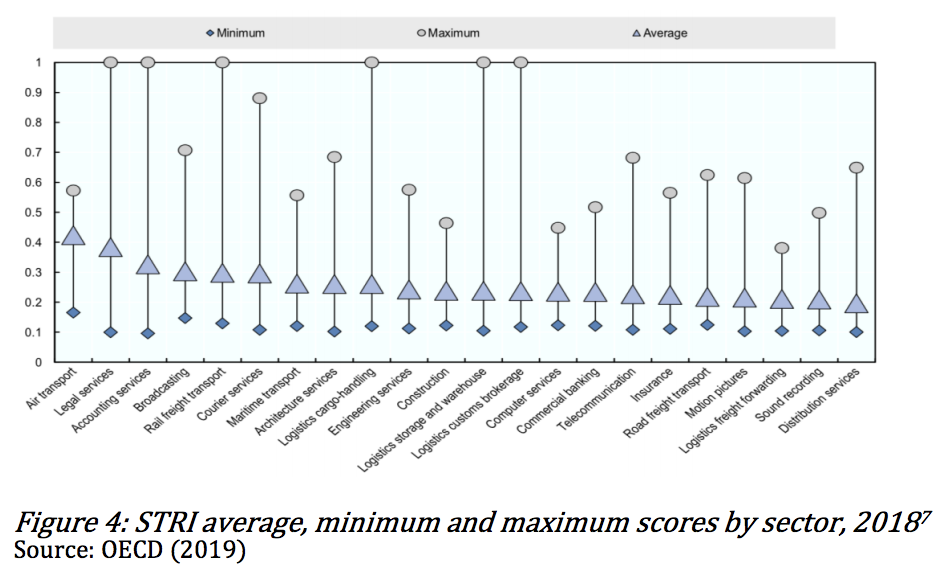

Despite faring relatively well in comparison with international commitments, applied restrictions in most services sectors are nevertheless rampant (Figure 4). These restrictions translate into sizable trade cost equivalents that significantly exceed average tariffs on traded goods. According to OECD (2019), the resulting price increases can be expressed in terms of tax equivalents that can reach up to almost 80% in certain countries, inflicting substantial additional costs on firms using these services as well as in higher prices for final consumers. These trade costs fall disproportionally on small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), which generally do not have the resources to deal with regulatory hurdles and divergences, resulting in an additional 7% in trade costs relative to large firms (OECD, 2019).

Policies need to be reviewed in order to stimulate trade

Against this background, it is of crucial importance that policy-makers place services at the center of their future work, reviewing their existing policies in view of the trends depicted in this brief. Given the relatively high level of restrictiveness in services trade policy, a careful reconsideration of existing policy and alignment with best practices that allows to reduce trade costs while maintaining regulatory priorities should be viewed as a low-hanging fruit for policy-makers eager to improve domestic economic performance. Failure to do so would imply a significant loss of growth and development opportunities. Collective efforts among economies to take stock of their existing policies in services such as underway in APEC are to be commended.

The G20 should support concerted action

Unilateral policy steps to audit national services trade and investment policies and regulations should be viewed in light of preparing the ground for concerted action by G20 countries to streamline their international commitments to reflect these realities. Recent initiatives on both a global and regional basis to enhance transparency and efficiency in domestic regulation of services sectors and to cooperate in developing a framework for international governance of ecommerce and digital trade are important steps in the right direction and should inspire momentum across all aspects of services trade and investment policy.

2 ILOSTAT, 2018

3 World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2018

4 Policy Brief 4 “The Digital Economy for Economic Development: Free Flow of Data and Back-up Policies” highlights the growing need to establish a holistic multilateral framework for e commerce and digital trade including liberalization of cross-border data flows.

5 The OECD STRI is a composite index that ranges between 0 (completely open) to 1 (completely closed).

6 This graph relies on the World Bank STRI that ranges between 0 (completely open) and 100 (completely closed).

7 The STRI covers all 36 OECD countries, Brazil, the People’s Republic of China, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Russian Federation, and South Africa

References

• Arnold, J. M., Javorcik, B., Lipscomb, M., & Mattoo, A. (2015). “Services reform and manufacturing performance: Evidence from India.” The Economic Journal, 126(590), 1-39.

• Ariu, A. (2016). “Crisis-proof services: Why trade in services did not suffer during the 2008–2009 collapse”. Journal of International Economics, 98, 138-149.

• Baldwin, R. (2019). The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics, and the Future of Work. Oxford University Press.

• Beverelli, C., Fiorini, M., & Hoekman, B. (2017). Services trade policy and manufacturing productivity: The role of institutions. Journal of International Economics, 104, 166-182.

• Borchert, I., & Mattoo, A. (2009). The crisis-resilience of services trade. The World Bank.

• Crozet, M., & Milet, E. (2017). “Should everybody be in services? The effect of servitization on manufacturing firm performance.” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy26, no. 4 (2017): 820-841.

• Fiorini, M., & Hoekman, B. (2018). “Services trade policy and sustainable development.” World Development, 112, 1-12.

• Gootiz, B. & Mattoo, A. (2017). “Services in the Trans-Pacific Partnership: What Would be Lost?” The World Bank.

• Handley, K., & Limão, N. (2017). “Policy Uncertainty, Trade, and Welfare: Theory and Evidence for China and the United States.” American Economic Review, 107 (9): 2731-83.

• International Monetary Fund (2018). “G-20 Report on Strong, Sustainable, Balanced, and Inclusive Growth”

• Kommerskollegium (2012). Everybody is in Services – The Impact of Servicification in Manufacturing on Trade and Trade Policy.

• Lamprecht, P., and Miroudot, S. (2019). “The Value of Market Access and National Treatment Commitments in Services Trade Agreements”, OECD Trade Policy Paper, forthcoming.

• Lee, W. (2018). “Services Liberalization and GVC Participation – New Evidence for Heterogeneous Effects by Income Level and Provisions”. Policy Research Working Paper WPS8475, the World Bank.

• McKinsey Global Institute (2019). Globalization in Transition: The Future of Trade and Value Chains

• Miroudot, S., & Shepherd, B. (2014). The paradox of ‘preferences’: regional trade agreements and trade costs in services. The World Economy, 37(12), 1751-1772.

• Miroudot, S. & Cadestin, C. (2017). “Services In Global Value Chains: From Inputs to Value-Creating Activities”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 197, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/465f0d8b-en

• Ngai, L. Rachel, & Petrongolo, B. (2017). “Gender Gaps and the Rise of the Service Economy.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 9 (4): 1-44.

• OECD (2019). “OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy Trends Up To 2019.”

• Roy, M. (2017). “The contribution of services trade policies to connectivity in the context of aid for trade.” WTO Working Papers.

• Roy, M. (2019). “Elevating Services – Services Trade Policy, WTO Commitments , and their Role in Economic Development and Trade Integration”, G-24 Working Paper.

• Schwarzer, J. (2015). “Services Trade and Employment.” CEP Discussion Note

• Stephenson, S. (2017). The Linkage between Services and Manufacturing in the U.S. Economy, Washington International Trade Association

• World Trade Organization (2018). “Overview of Developments in the International Trading Environment” Annual Report by the Director-General

• WTO/OECD (2018). “Trade in value added (Edition 2018)”, OECD-WTO: Statistics on Trade in Value Added (database) https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIVA_2018_C1 (accessed on 25 February 2019).