Roughly one-seventh of humanity lives in countries mired in poverty. With inequality on the rise, many people do not have access to education, public services, and good jobs. These challenges are especially notable in cities; 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in cities by 2050. An effort to reduce inequality, in line with the UN’s 2030 Agenda and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, will require G20 nations to promote inclusive economic and social growth agendas throughout their metropolitan areas and beyond. To this end, we propose that the G20 adopt a series of best practices inspired by what we call “Smart Decentralization.” Our concept of Smart Decentralization applies an urban convergence framework to reconfigure the formulation of city policy with the goal of encouraging good local governance, improved participation, and strengthened accountability at the sub-national and local levels.

This policy brief has five key recommendations for central and state governments: That they (1) jump-start community development, (2) delegate key powers to local governments, (3) encourage the development of community organizations, (4) develop institutions of downward accountability for local political leaders, and (5) promote “polycentric” cooperation among relevant governmental and non-governmental actors at all tiers. With this general framework serving as a baseline, we propose the inception of an intergovernmental panel tasked with developing specific best practices that can be transposed to a variety of institutional settings. Our hope is that these Smart Decentralization best practices will ultimately be applied within the G20, as well as more broadly, through their incorporation into foreign aid packages developed by G20 members and multilateral donors.

Challenge

As 70% of the global population is expected to live in metropolitan areas by 2050, the world’s cities are faced with unprecedented challenges (ISUH n.d.). First among these is the imperative to develop economically while ensuring that communities are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable (UN, n.d.). Reconciling these tensions requires more than economic reform. It also demands, as stated in the G20 policy goals, “improving the governance, legitimacy, accountability, and trust in state institutions.” (T20 Recommendations Report 2020, p. 32) (Appendix A).

It is clear from past research and experience that solutions to local challenges imposed from on-high are rarely effective. The information asymmetries make it simply impossible for central authorities to understand the needs of local citizens to the extent necessary to govern well. Moreover, national governments are not usually in a position to differentiate the policies and public goods that they deliver according to local needs (Bird et al. 2003; Lockwood 2002; Oates 1972).

By the same token, purely bottom-up approaches rarely deliver the good governance and poverty alleviation that governments and their citizens desire. Spillover effects mean that local authorities need to coordinate with their counterparts both at the same tier and at higher tiers, and this can rarely be done successfully without central and state government buy-in (Oates 1972). Moreover, the resources that can only be mobilized by central and state governments are critical to success.

What is needed, then, is a combined approach. The on-the-ground knowledge and local accountability of urban authorities must be harnessed to address the challenges of the future. This imperative includes not only the necessity of engaging the strengths of formal local governments; it also requires the promotion of structured community development organizations.

At the same time, central and state governments must remain fully engaged. At a basic level, they must consider which powers to maintain and which to delegate or devolve to lower tiers. But more than that, higher-tier leaders should support local efforts with the resources and coordinated policy direction that only they can provide. For these reasons, we propose an integrated approach, one best captured by the term “Smart Decentralization.” We lay out this approach below.

Proposal

This policy brief suggests that the G20 adopt a series of best practices inspired by what we call Smart Decentralization. To develop these best practices in detail, we recommend the inception of an intergovernmental panel—perhaps by utilizing the established U20 platform (Appendix B). This panel would address governance, public goods, and inequality in the G20’s largest cities. It would use the principles of Smart Decentralization as a baseline for the common shared interest of advancing accountability and economic improvement in urban areas. Its membership would comprise researchers and practitioners from each G20 nation. These experts would provide specific recommendations based on the spirit of Smart Decentralization that are suitable for varying governmental systems. Once these Smart Decentralization best practices have been developed, they could be applied within the G20 as well more broadly, through their incorporation into foreign aid packages developed by G20 members and multilateral donors.

The goal of these best practices would be to reconfigure how policy making is approached in cities by focusing on inclusive metropolitan growth. Using an urban convergence framework, which encourages local participation in urban development, governments would direct their efforts toward bridging local issues with a national response (Appendix C). Simultaneously, they would lay the foundation for social and economic advancement through key decentralization policies and procedures. Adopting best practices within this framework would create pathways toward good governance and equality in cities by focusing on a series of integrated policies and approaches. These would combine both top-down and bottom-up elements of urban local governments that can strengthen state institutions, promote accountability, provide equal opportunities, and foster community development.

Why focus on Smart Decentralization as a tool to meet the governance challenges of the future? If all citizens are to feel represented by their government, the government must be brought closer to them in ways that allow their participation. This should promote social stability, reduce corruption, and stimulate economic growth, as indicated by many studies.[1] It will also help gather more data about local preferences and allow different locales to be used as test cases for new policy ideas. If central governments use the latest research and experience, they can create effective local governance mechanisms while assisting urban communities in their efforts to tackle the challenges of tomorrow. This is how we define Smart Decentralization.

To ensure effective results, the Smart Decentralization best practices should consist of two components. First, they should lay out a series of universal requirements that are necessary for effective decentralization programs. Second, they should identify a series of specific mechanisms, both formal and informal, political and consultative, that can help achieve these requirements in different cultural contexts. In the sections that follow, we develop principles that can serve as a starting point for the panel’s work.

The Principles of Smart Decentralization

Considering the need to remain flexible, we identify five principles that must be present if urban decentralization and community engagement are to be successful. These should form the heart of any series of Smart Decentralization best practices.

Principle 1: G20 central and state governments should “jump-start” community development in cities by (1) investigating local needs, (2) committing resources for key projects to create public interest and promote equality, and (3) exploring local governance capacity and potential partnerships.

Building local governance capacity can take time. The panel should encourage central and state governments to begin identifying resource gaps in city neighborhoods, specifically in low-income areas, to jumpstart revitalization efforts.

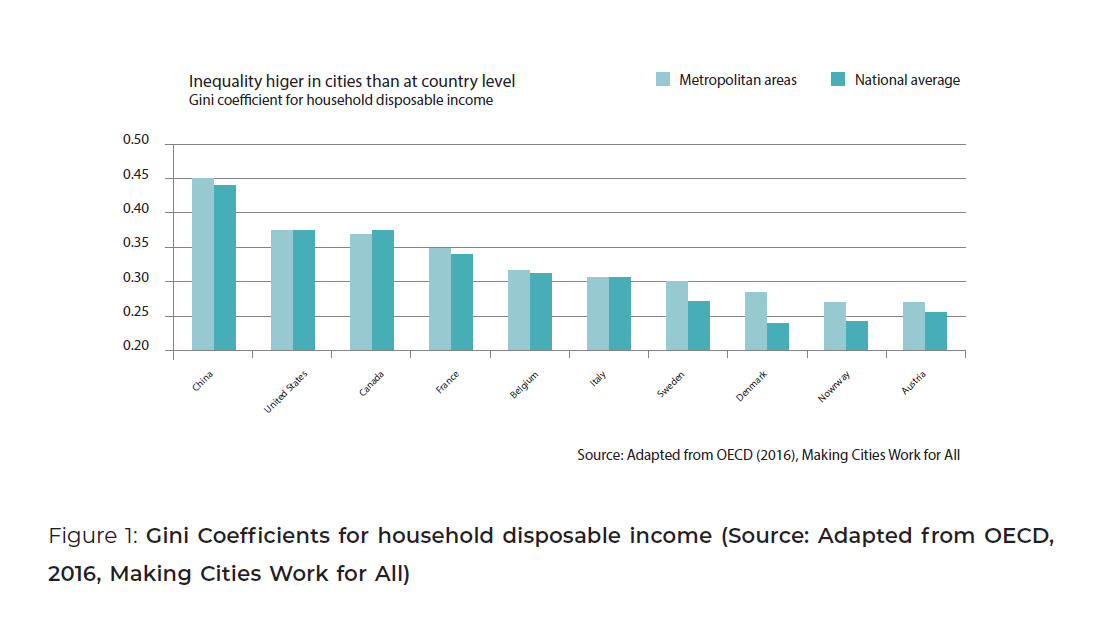

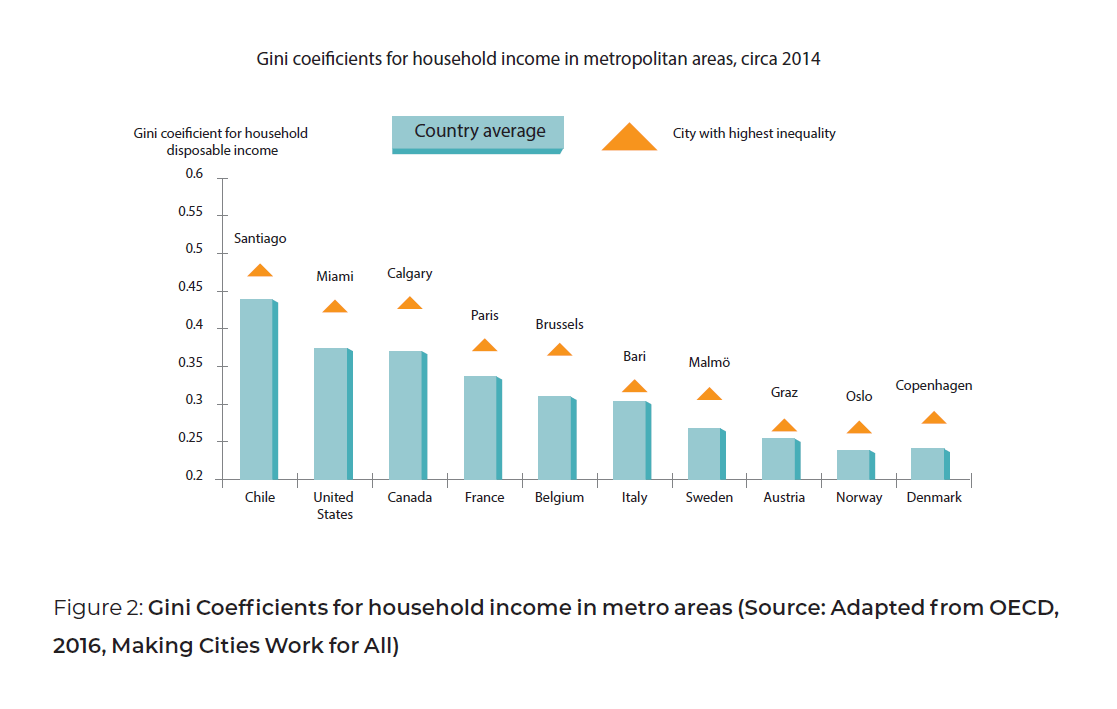

Data from nine out of ten cities studied by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) show that urban areas have higher inequality coefficients than is average for the countries in which they are located (Figure 1) (2016). Further analysis suggests that cities become more unequal as they grow (Figure 2), creating potential drivers for inequality that impact the national level.

Higher-tier governments should examine citizens’ primary needs by conducting inhabitant satisfaction surveys using the community voicing approach on a city level to help identify key issues. They should then proceed with the necessary public works upgrades identified in their findings to initiate quick “wins.”

Such wins should be focused on increasing the quality of life in low-income neighborhoods, which could be as simple as improving public works (sidewalks, lighting, landscape) and services (waste management, security). Of course, it is critical that this central and state involvement not threaten to replace local autonomy. On the contrary, a key goal of these initiatives should be jumpstarting public engagement with a new or newly empowered local government.

Since funding availability differs from one country to another, alternative methods of raising capital could assist authorities in beginning local efforts. Tapping into the private sector, social partners, and non-governmental organizations to perform initial neighborhood wide surveys (Appendix D) could promote social responsibility initiatives from organizations within communities.

For the actual public works upgrades needed, the creation of “urban community funds” could boost these efforts. Other capital sources could also be utilized, including funding from developers looking to gain additional floor area ratio incentives. In urban settings, this approach is commonly used around the world.

Principle 2: Central and state governments should delegate the responsibility and capacity to provide urban public goods to local leaders. This should include, at a minimum, expenditure powers over roads, water, waste, and perhaps primary education and health. It should also include support in creating an effective and accountable civil administration through which these powers can be exercised.

In considering its recommendations, the panel would need to account for a vast body of literature, applying its lessons to the particular circumstances faced by individual countries.

Public finance scholars emphasize that urban governments will lack autonomy unless they possess both expenditure authority and the power to raise their own revenue (Hines 1995; Von Hagen 2002). Expenditure authority allows local governments to decide how their budgets are spent, while control over revenues implicates the more basic power to decide on the size of government itself. Which expenditure and revenue policies should local city governments be allocated? There is a large body of literature on this subject which emphasizes that polices with few spillover effects are best left to local governments (see Hankla 2008). These will generally include control over local roads, waste, water, electricity, zoning and building use, parks and recreation, and sometimes primary education and health. On the revenue side, city governments should normally tax fixed assets such as property, or should derive their income from user fees, sales taxes, or fixed and stable transfers from a higher tier (Shah 2003).

Moving outside the fiscal arena, researchers and practitioners have pointed out that local governments will be unable to exercise their authority if they lack control over a competent civil service.

In some countries, India for example, many local civil servants remain accountable to central or state governments even when they report to local authorities (Prabhakar 2011). Moreover, in many developing countries, it is difficult to find civil servants at the local level because well prepared candidates gravitate toward the central administration (Manor 1999). Dealing with these challenges will require creative solutions, such as administrative sharing programs between central, state, and local governments, with each tier having specific forms of authority over civil servants (Momoniat 2002) (Appendix E).

Principle 3: G20 central and state governments should encourage the development and participation of community organizations in future local policy formation and implementation. This should be done by providing city governance platforms that can lead local urban development efforts, which can then create grassroots movements that foster upward social and economic mobility.

It is critical for the panel to encourage the combination of decentralization and a bottom-up approach. This enables community members to raise proposals and initiatives with their newly empowered local governments.

In this context, there are three starting-point strategies that can contribute to successful neighborhood engagement (Dreier 1996):

- Community organizing: voicing community feedback in decision-making to promote development.

- Community-based development: delivering physical and economic improvements related to the built environment via infrastructure, services, and public works.

- Community-based service provisions: providing social services aimed at improving the quality of life and opportunities of people living in cities and neighborhoods (Appendix F).

Community led local development (CLLD) and urban-rural linkages, introduced in the European Union, promote participatory initiatives that spearhead partnerships, civic society strengthening, and urban development. These tools represent a promising supplement to more formal political institutions at the local level.

Implementing CLLD guidelines is essential to encourage community participation. These guidelines use an integrated, bottom-up approach to address territorial and local challenges that urgently need a response. Community members can launch a CLLD by following three basic steps: initiating the partnership, assigning the concern and strategy, and determining area coverage (European Commission 2013).

After gaining approval from the central government, the CLLD unit should then be led by a Local Action Group (LAG). The LAG should be made up of local public, private, and community representatives and is responsible for the implementation of specific initiatives in its defined area. Urban concerns, such as sufficient affordable housing, adequate infrastructure and services, displacement mitigation, matching local skills to job opportunities, and building community capacity in low-income neighborhoods are among the many issues that can be addressed locally (Appendix G).

Following Principle 2, these CLLD units should have the administrative, fiscal, and political autonomy to act upon citizen needs from a local perspective. This empowers the community to initiate change by involving them in the policy process. Such an approach would ensure that grassroots consultation is at the center of local initiatives. Collectively, this would include the participation of end-users and address socioeconomic concerns through subsequent urban-rural linkages.

One example of an effective local community organizing instrument is participatory budgeting (Shah 2007). This practice, which has gained recognition worldwide in the past decade, takes different forms in different places. In general, it involves local (and sometimes state and national) officials holding a series of public meetings to elicit feedback and budget proposals from the public. In many places, the practice is also used to increase the involvement of women and underrepresented groups in the budgeting process.

Principle 4: Central and state governments should ensure that urban political leaders are held accountable for providing the public goods required to respond to local preferences and needs. This can be done by holding competitive elections, benchmarking and interjurisdictional competition, transparency rules, participatory budgeting, civil society strengthening, and other mechanisms.

The panel of experts must build accountability into their recommendations from the beginning and create enough flexibility to fit a wide variety of institutional settings.

Researchers have long emphasized the critical role of competitive elections in ensuring accountability, both at the national and local levels (Hallerberg 2004; Hecock 2006; Wibbels 2000). Elected officials, especially when they fear losing their seats, are strongly incentivized to provide their constituents with the public goods that they desire.

More recently, some scholars have also pointed to the vital role played by upward accountability from local governments to authorities at higher tiers (Filippov, Ordeshook and Shvetsova 2004; Hankla, Martinez-Vazquez and Rodriguez 2019). When locally elected officials are responsible to both their citizens and higher-tier party leaders and governments, they have an incentive to coordinate their policies and to think beyond their own constituencies.

In addition to downward and upward accountability, horizontal competition and benchmarking can be a source of local accountability. Barry Weingast (1995) has argued that when local constituencies compete with one another for citizens and taxpayers, they are driven to improve. China’s policy of collecting and publishing economic data for its provinces and cities, and then using these data to reward and punish local leaders, is an example of such an approach.

Of course, there are a variety of institutional configurations and governance approaches that can be adapted to local circumstances. For example, an advisory council of local notables and representatives of various interest groups can make the local government more open. In many countries, such as Mozambique, traditional chiefs are represented within these advisory bodies (Hankla and Manning 2016; Orre 2010).

Outside of formal local councils and advisory bodies, civil society can play a very productive role in increasing accountability. Donors, including G20 members, can encourage this role through funding local civil society organizations in the developing world. They can also encourage accountability by fighting local corruption and by promoting strong norms of openness and propriety at the local level.

Another pro-accountability approach is to implement transparency rules that require local governments to release information and to hold open meetings. Programs that fund voter education can also encourage citizens to use their influence more effectively. Technical training for local council members, such as the program recently funded in Vietnam by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), can improve budgetary oversight (Hankla 2014).

Principle 5: Central and state governments should promote polycentric cooperation among various local, regional, and national entities, such as formal governments, community organizations, or private actors, to ensure interjurisdictional equality and efficient provision of urban public goods.

The previous principles have emphasized the structure and powers of local governments as well as means of encouraging community participation. There is one final principle for the panel to consider, which focuses on often-neglected elements of decentralization. That is, the relationships between local governments, and the relationships between local governments and other relevant governance actors. Such considerations are critical in large urban settings where multiple local authorities must cooperate with higher authorities, private actors, and one another to provide the best public services.

Cooperation among different local constituencies will often produce better outcomes. On a macro level, for example, the C40 network connects the world’s megacities in addressing the issue of climate change and delivering on the goals of the Paris Agreement.

More frequent cooperation, however, happens at the micro level. Local governments worldwide regularly engage in agreements with their neighbors to jointly provide public goods that would be difficult for them to provide independently (de Mello 2019; Ermini and Santolini 2010). A useful recent example is France, where degrees of coordination among communities are available for different circumstances (Frère Leprince and Paty 2014). Such cooperation is important for the governance of large urban communities, since they often have several different local authorities holding responsibility.

From a fiscal standpoint, the traditional view of expenditure assignment holds that public goods are most efficiently provided by a single responsible tier of government. However, a number of scholars, notably inspired by the work of Elinor Ostrom (2010), have rejected this notion in favor of a polycentric view of public goods production. This view holds that public goods, at least under certain circumstances, can be provided by multiple governmental levels, along with a variety of private and community actors, working together in a coordinated fashion. Such an approach allows each actor to focus on its strengths while avoiding its weaknesses. It is also a more realistic representation of actual decision-making and implementation processes in complex polities, including those of large metropolitan areas.

Finally, it is a staple of fiscal policy to channel extra funding to poorer local constituencies in order to counter inequality risks that may emerge from decentralization (Litvack, Ahmad and Bird 1998). There is also the potential risk that different levels of social capital in different locales could lead to highly unequal outcomes in the wake of decentralization reform (Putnam, Leonardi and Nonetti 1993). In particular, there is the risk of exacerbating an existing urban-rural divide. Additional funding, along with supplementary support from the central government, can help mitigate these issues, but any future best practices must take them into account. This is particularly important since regional inequality has been traced to increased civil violence in highly divided societies (Østby, Nordås and Rød 2009).

This research clearly indicates that the Smart Decentralization best practices should encourage, as a principle, the use of equalization grants and other mechanisms to ensure that decentralization does not increase inequality. They should also promote the creation of a diverse array of location specific cooperative agreements between local, regional, and national governments, and organizations to capitalize on the relative strengths of each actor for local public goods provision. These goals must be pursued, however, within the context of an enduring respect for local accountability, so that power over local affairs rests ultimately with representatives of the community.

Conclusion

The G20, as the world’s central forum for economic policy coordination, can play a unique role in promoting effective decentralization policies. The Saudi presidency’s emphasis on the empowerment of citizens makes it appropriate for the G20 to address issues of local governance now.

Though organizations such as the OECD and UN have considered sustainable partnerships a priority, the G20’s participation in setting best practices is critical in encouraging effective decentralization reform. This is particularly true given that the members of the G20 are also the core providers of development aid, which has long played a role in promoting institutional reform, including decentralization, in recipient countries.

Creating an international panel of experts and practitioners under the auspices of Smart Decentralization would help generate a comprehensive framework for promoting decentralization reforms. These reforms would be applied first to cities, which face extraordinary challenges over the next several decades and generally possess better administrative resources. They could then be adapted to less populated areas, which often suffer from worse poverty and are frequently in dire need of improved governance.

As a final analysis, our hope is that the promotion of decentralization and improved governance through a single framework will assist international efforts to make our cities more dynamic and, ultimately, to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by “leaving no one behind” (2018).

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Bird, Richard, Bernard Dafflon, Claude Jeanrenaud and Gebhard Kirchgässner. 2003.

“Assignment of Responsibilities and Fiscal Federalism.” In Federalism in a Changing

World: Learning From Each Other, edited by Raoul Blindenbacker and Arnold Koller,

351-72. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Brancati, Dawn. 2009. Peace by Design: Managing Intrastate Conflict Through

Decentralization. New York: Oxford University Press

Collier, Paul. 2007. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and

What Can Be Done About It.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Czischke, Darinka and Simona Pascariu. 2015. “New Concepts and Tools for

Sustainable Urban Development in 2014 – 2020.” URBACT website, Report. Last

updated September 2015. https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/synthesis_report_urbact_study.pdf.

Davoodi, Hamid and Heng-fu Zou. 1998. “Fiscal Decentralization and Economic

Growth: A Cross-Country Study.” Journal of Urban Economics 43: 244-57.

De Mello, Luiz. 2019. Local Government Cooperation: Challenges, Trends and

International Experience. Paris: OECD Working Paper.

Dreier, Peter. 1996. “Community Empowerment Strategies: The Limits and Potential

of Community Organizing in Urban Neighborhoods.” Cityscape 2 no. 2: 121–59.

Ermini, Barbara and Raffaella Santolini. 2010. “Local Expenditure Interaction in Italian

Municipalities: Do Local Council Partnerships Make a Difference?” Local Government

Studies 36 no. 5: 655-677. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2010.506979.

European Commission. 2013. “Community-Led Local Development: Cohesion Policy

2014-2020.” European Union website, Facsimile. Last updated March 2014. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/informat/2014/community_en.pdf.

Filippov, Mikhail, Peter C. Ordeshook and Olga Shvetsova. 2004. Designing

Federalism: A Theory of Self-Sustainable Federal Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Frère, Quentin, Matthieu Leprince and Sonia Paty. 2014. “The Impact of Intermunicipal

Cooperation on Local Public Spending.” Urban Studies 51 no. 8: 1741-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013499080

Gurgur, Tugrul and Anwar Shah. 2002. Localization and Corruption: Panacea or

Pandora’s Box? In Managing Fiscal Decentralization edited by Ehtisham Ahmad and

Vito Tanzi. New York: Routledge.

Hallerberg, Mark. 2004. Domestic Budgets in a United Europe: Fiscal Governance

From the End of Bretton Woods to EMU. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hankla, Charles R. 2008. “When is Fiscal Decentralization Good for Governance?”

Publius: The Journal of Federalism 39 no. 4: 632‒665. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjn034

Hankla, Charles. 2014. “Delivering Budget Training to Subnational Government in

Vietnam.” International Budget Partnership Newsletter, Jul-Aug 2014. https://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/Newsletter-79-FINAL.pdf.

Hankla, Charles R. and Carrie Lynn Manning. 2017. “How Local Elections Can Transform

National Politics: Evidence from Mozambique.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism

47 no 1: 49‒76. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjw023.

Hankla, Charles R., Jorge Martinez-Vazquez, and Raul Ponce Rodriguez. 2019. Local

Accountability and National Coordination in Fiscal Federalism: A Fine Balance.

Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Hecock, R. Douglas. 2006. “Electoral Competition, Globalization, and Subnational

Education Spending in Mexico, 1999-2004.” American Journal of Political Science 50

no. 4: 950-961. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00226.x.

International Society for Urban Health (ISUH). n.d. “Challenges: Rapid Urbanization

Around the Globe.” ISUH website. Accessed January 5, 2020. https://isuh.org/about/why-urban-health/challenges.

Hines, James and Richard Thaler. 1995. “The Flypaper Effect.” Journal of Economic

Perspectives 9: 217-26. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.4.217.

Litvack, Jennie, Junaid Ahmad, and Richard Bird. 1998. Rethinking Decentralization

In Developing Countries. Washington: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-4350-5.

Lockwood, Ben. 2002. Distributive Politics and the Costs of Centralization. Review of

Economic Studies 69 (2): 313–338.

Manor, James. 1999. The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralization.

Washington: World Bank https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-4470-6.

Momoniat, Ismail. 2002. “Fiscal Decentralization in South Africa: A Practitioner’s

Perspective.” In Managing Fiscal Decentralization edited by Ehtisham Ahmad and

Vito Tanzi. New York: Routledge.

Oates, Wallace E. 1972. Fiscal Federalism. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

OECD. 2002. “Policy Coherence.” OECD Journal on Development 3: 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1787/journal_dev-v3-art20-en.

OECD. 2016. Making Cities Work for All: Data and Actions for Inclusive Growth Paris:

OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264263260-en.

Orre, Aslak Jangård. 2010. “Entrenching the Party-State in the Multiparty Era:

Opposition Parties, Traditional Authorities and New Councils of Local Representatives

in Angola and Mozambique.” PhD dissertation, University of Bergen, Norway.

Østby, Gundrun, Ragnhild Nordås and Jan Ketil Rød. 2009. “Regional Inequalities

and Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Studies Quarterly 53 no. 2,

301-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00535.x.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2010. “Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of

Complex Economic Systems.” American Economic Review 100 no. 3: 641-72. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.3.641.

Prabhakar, R. P. 2011. “Local Government’s Administrative System in India.” The Indian

Journal of Political Science 73 no. 4: 943-52.

Putnam, Robert D., with Robert Leonardi and Richard Y. Nonetti. 1993. Making

Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. New York: Princeton University

Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400820740.

SDSN. “SDG Index and Dashboards Report for European Cities.” Sustainable

Development Report, Bertelsmann Stiftung website. Last updated July 20, 2019

https://sdgindex.org/reports/sdg-index-and-dashboards-report-for-european-cities.

Shah, Anwar. 2003. “Fiscal Decentralization in Transition Economies and Developing

Countries.” In Federalism in a Changing World: Learning From Each Other edited by

Raoul Blindenbacker and Arnold Koller, 432-60. Montreal: McGill-Queens University

Press.

Shah, Anwar. 2007. Participatory Budgeting. Washington: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6923-4.

Smoke, Paul. 2006. “Fiscal Decentralization in Developing Countries.” In Public Sector

Reform in Developing Countries, edited by Yusuf Bangura and George A. Larbi. New

York: Palgrave McMillan.;

T20 Recommendations Report. 2020. “Social Cohesion and the State.” T20

website. Accessed August 8, 2020. https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/g20-insights-uploads/2020/04/T20-Recommendations-Report-Social-cohesion-and-the-state.pdf.

Tanzi, Vito. 2002. “Pitfalls on the Road to Fiscal Decentralization.” In Managing

Fiscal Decentralization edited by Ehtisham Ahmad and Vito Tanzi, 17-30. New York:

Routledge.

Treisman, Daniel. 2007. The Architecture of Government: Rethinking Political

Decentralization. New York: Cambridge University Press

United Nations Development Programme. 2018 (UNDP). “What Does It Mean To Leave

No One Behind? A UNDP Discussion Paper and Framework for Implementation.”

UNDP website, Last updated, July 2018. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Sustainable%20Development/2030%20Agenda/Discussion_Paper_LNOB_EN_lres.pdf.

United Nations. N.d. “Goal 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe,

Resilient, and Sustainable.” United Nations website. Accessed January 5, 2020.

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg11.

UNRISD. 2016. “Policy Innovations for Transformative Change: UNRISD Flagship

Report 2016.” UNRISD website. Last updated October 2016. http://www.unrisd.org/80256B42004CCC77/(httpInfoFiles)/2D9B6E61A43A7E87C125804F003285F5/$file/Flagship2016_FullReport.pdf.

Von Hagen, Jürgen. 2002. “Fiscal Federalism and Political Decision Structures.”

In Federalism in a Changing World: Learning From Each Other, edited by Raoul

Blindenbacker and Arnold Koller, 373-94. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Wahba, Sameh and Judy Zheng Jia. 2018. “Spatially Awhere: Bridging the Gap

Between Leading and Lagging Regions.” World Bank Blogs. Last Updated May 31,

2018. https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/spatially-awhere-bridging-gapbetween-leading-and-lagging-regions.

Weingast, Barry R. 1995. “The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-

Preserving Federalism and Economic Growth.” Journal of Law, Economics, &

Organization 11 no 1: 1-31.

Wibbels, Erik. 2000. “Federalism and the Politics of Macroeconomic Policy and

Performance.” American Journal of Political Science 44 no. 4: 687-702. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669275.

World Bank. 2003. “Case study 1 – Bangalore, India: participatory approaches in

budgeting and public expenditure management (English).” Social Development

Notes; no. 70. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/437121468774893355/Case-study-1-Bangalore-India-participatory-approaches-in-budgeting-and-publicexpenditure-management.

World Bank. 2019. Kenya’s Devolution. World Bank Website. Accessed August 7, 2020.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/brief/kenyas-devolution

Yilmaz, Serdar, Yakup Beris and Rodrigo Serrano-Berthet. 2008. “Local Government

Discretion and Accountability: A Diagnostic Framework For Local Governance.” Paper

No.113, Social Development Working Papers, Local Governance and Accountability

Series. Washington: The World Bank.

Appendix

[1] . There is evidence for each of these effects of decentralization, but also some controversy (Brancati 2009; Davoodi and Zou 1998; Gurgur and Shah 2000; Manor 1999; Smoke 2006; Tanzi 2002; Treisman 2007; Yilmaz, Beris and Serrano-Berthet 2008).