The COVID-19 pandemic serves as an important reminder for the need for global solutions and solidarity among nations to address global challenges. This includes the challenges articulated within the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This policy brief seeks to harness the expertise and experience of the Group of 20 (G20) partnership to accelerate the quality monitoring of Target 4.7 under SDG 4. It proposes the establishment of structures that enable more holistic tracking of the integration of education for sustainable development and global citizenship within policies, teacher education, curricula, and learner assessment at all levels of education.

Challenge

This policy taskforce prioritizes making improvements in the G20’s capacity to monitor progress on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly 2015). Given the limited time remaining to address the challenges within Agenda 2030, this policy brief proposes actions that can accelerate the monitoring of progress made by G20 countries toward achieving Target 4.7[1] under SDG 4. Target 4.7 is concerned with the implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and Global Citizenship Education (GCED) within policies, teacher education, curricula, and assessment at all levels of education.

ESD[2] and GCED[3] are both understood within this policy brief as educational processes that empower learners to make critically informed decisions and take actions that ensure economic, environmental, societal, and cultural sustainability for present and future generations (UNESCO 2014, 2015, 2019d). GCED is understood as fostering peaceable futures by engendering “a sense of belonging [among learners] to a broader community and common humanity” (UNESCO 2015, 14). There are different understandings and applications of ESD and GCED within and across countries (Pashby 2015; Dower and Williams 2016; Akkari and Maleq 2019). Some argue that these educational processes can promote capitalist dominated agendas and (Western) worldviews driving neoliberalism and individualism (Sharma 2018, 2020; Dill 2012, 2013). Thus, they re-enforce unequal power relations (Jickling and Wals 2008; Hellberg and Knutsson 2016; Holfelder 2019; Sjögren 2019) and practices that can be “dissociated from local needs and realities” (UNESCO 2018a, 2).i

Progress toward achieving Target 4.7, specifically the implementation of ESD-GCED at the national level, must be assessed. Therefore, ESD-GCED evaluation frameworks that are culturally responsive, scalable, and adjustable, and that examine cognitive, social and emotional, and behavioral dimensions of sustainability and global citizenship must be developed (UNESCO 2019d). The varying, multi-layered, and evolving nature of ESD and GCED must also be considered. In 2018, the SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee recommended that governments should establish holistic national evaluation and learning assessment systems and conduct cross-national assessments in education to assess progress in reaching targets outlined under SDG 4 (Paul 2018; UNESCO 2018c). A significant challenge in establishing these more holistic national evaluation processes vis-à-vis Target 4.7 is the dearth of models (operationalized at a country level) that integrate qualitative forms of assessment while monitoring ESD-GCED integration. There have been criticismsii of the conflicting motivations in and competitive nature of certain large-scale assessments in education exercises (Morris 2016; Engel, Rutkowski, and Thompson 2019; Goren et al. 2020). There have been concerns about their democratic deficits (Sousa, Grey, and Oxley 2019), lack of cultural responsiveness, and ineffectiveness in using these instruments to examine the ESD-GCED integration and outcomes. There are claims that large-scale international assessments mainly assess Western notions of global competence with little or no recognition of the assessment of (local) knowledge, skills, values, or actions (Auld and Morris 2019a, 2019b). Finally, as this policy brief will illustrate, there is considerable variation in the participation of G20 countries in large-scale international education assessment exercises. This presents challenges for any proposed national or cross-national analysis of their contributions to Target 4.7.

This policy brief calls for the establishment of a collaborative strategy among G20 partner countries to develop holistic assessment frameworks that can be deployed to monitor progress in implementing ESD-GCED at the national level. These frameworks will enable the capture and interpretation of relevant assessment data from both large-scale international assessments in education and qualitative case studies on ESD-GCED integration that are grounded locally.

Proposal

This policy brief proposes the formation of a collaborative strategy to monitor progress on the implementation of ESD and GCED across the G20 countries. The G20 Collaborative Strategy will focus the efforts of the G20 partnership on accelerating monitoring through the design and implementation of holistic frameworks for mapping progress on ESD-GCED at the local and national levels. The creation and enactment of this collaborative strategy on ESD-GCED by the G20 partnership will demonstrate the seriousness of its commitment to track progress in achieving Target 4.7 under SDG 4. It will provide evidence of ESD-GCED integration and accompanying outcomes. To ascertain the progress made toward achieving Target 4.7 within the G20 partnership, it will be necessary to articulate qualitative and quantitative means for assessing the ESD-GCED integration, learners’ performance, and translational actions of learners for sustainability. By collating both qualitative and quantitative data, the G20 partner countries can track the extent to which ESD-GCED is visible in policies, teacher education programs, and curricula more holistically. They can assess its effectiveness in fostering sustainability-minded and action-oriented learners. This section begins with an overview of the performance indicators for Target 4.7, as articulated under Agenda 2030. It proceeds to highlight assessment instruments that can provide data on these indicators. The final section summarizes the key recommendations for the development and implementation of a G20 Collaborative Strategy.

Indicators for Target 4.7: Measurement of success

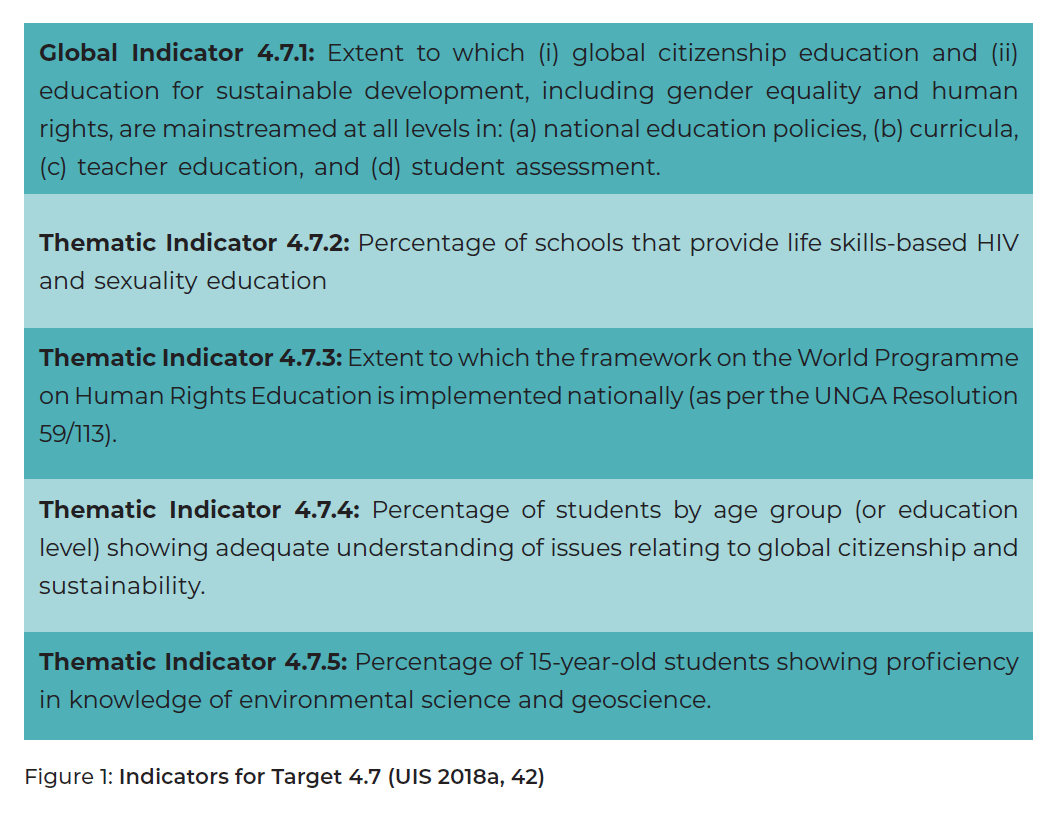

Target 4.7 under SDG 4 aims to enhance sustainability knowledge and skills and to re-orient dispositions of learners toward living more sustainably through ESD and GCED. It has one global and four thematic indicators that are used to benchmark its progress (Figure 1).

Global indicator 4.7.1 is a country-level measure of progress on mainstreaming ESDGCED within educational policies and related systems (specifically within curricula, teacher training, and student assessments). The four thematic indicators are quantitative measures of progress toward the integration of life skills-based HIV and sexuality education (4.7.2) and human rights education (4.7.3), as well as outcomes measures relating to learners’ levels of understanding of global citizenship and sustainability (4.7.4), and attainment in related environmental and geoscience domains (4.7.5) in curricula. This policy brief focuses on addressing the current gap in monitoring and assessing progress vis-à-vis implementing education for sustainability and global citizenship in G20 countries. It focuses on indicators 4.7.1, 4.7.3, 4.7.4, and 4.7.5 under Target 4.7. It does not include any further discussions on the assessment of indicator 4.7.2, as a separate policy brief is warranted to fully examine structures to monitor progress on the integration of life skills-based HIV and sexuality education.

Monitoring Target 4.7: Assessment in Education instruments

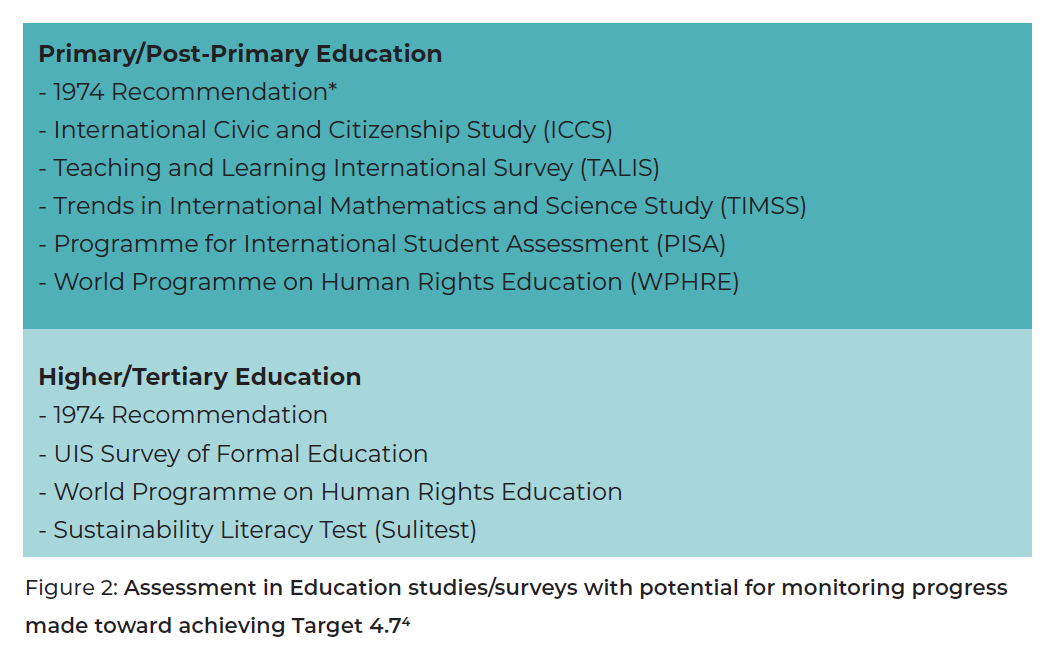

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) is the lead agency for monitoring SDG 4. Its Institute for Statistics (UIS) works with partners to develop indicators and assess progress made toward achieving the international education targets outlined in Agenda 2030. Several studies or surveys of education can be used to monitor aspects of the implementation of ESD-GCED and the performance of learners in mainstream contexts (Figure 2). The merits and demerits of particular large-scale assessments vis-à-vis ESD-GCED are explained substantively in this section. However, this policy brief does not recommend the sole use of a largescale international assessment through education instruments to monitor Target 4.7. Instead, as detailed in the recommendations at the end, this proposal advocates the integration of national ESD-GCED assessment frameworks, where data is drawn from a combination of large-scale assessment instruments, case studies, and other research exploring the implementation and evaluation of sustainability and GCED at local levels.

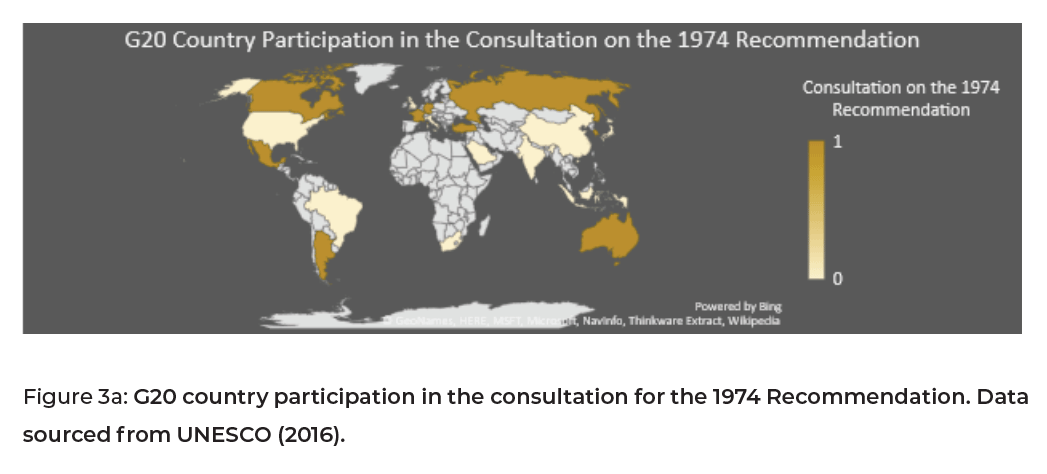

The data for monitoring progress in relation to global indicator 4.7.15 have been drawn solely from UNESCO’s quadrennial “Consultation on the Implementation of the 1974 Recommendation Concerning Education for International Understanding, Cooperation and Peace relating to Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms” (“1974 Recommendation”) since 2016. The 1974 Recommendation consultation process involves governments self-reporting on their progress vis-à-vis human rights related policy and practice at the national level and providing supporting evidence on the infrastructure in place (UIS and GAML 2017). The self-reporting nature of this consultation exercise has raised concerns around validity, such as the risks of misunderstanding and social desirability bias (UIS 2018c). However, as Benavot (2019) argued, the information submitted is made available publicly and is thus open to being challenged if found incorrect by observers on the ground. An additional concern is the focus on assessing the type of structures in-situ for integrating ESD-GCED (including national education policies, teacher education, curricula, and assessment frameworks) rather than actual practices and outcomes within schools and learning contexts. As noted by Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda (2019), each country’s performance with respect to global indicator 4.7.1 is primarily measured in terms of the intended ESD-GCED curriculum rather than the attained or implemented curriculum. Despite this, the United Nations Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG indicators has foregrounded the 1974 Recommendation consultation process within the approved method for measuring progress made on indicator 4.7.1 (UNESCO 2019b). Therefore, it would appear prudent for the G20 to consider the integration of data from the 1974 Recommendation consultation within any proposed framework for monitoring progress made toward achieving Target 4.7. Alternatively, if some partner countries are opposed to engaging in the 1974 Recommendation consultation process, there will be a need for G20 countries to seek or develop other survey instruments and processes that can help monitor performance relating to global indicator 4.7.1.

Progress on indicator 4.7.3 has been monitored to date through the implementation of a framework known as the World Programme on Human Rights Education (WPHRE).6 The WPHRE examines the provision of human rights education in educational institutions through data provided by governments and national human rights organizations from individual countries.7

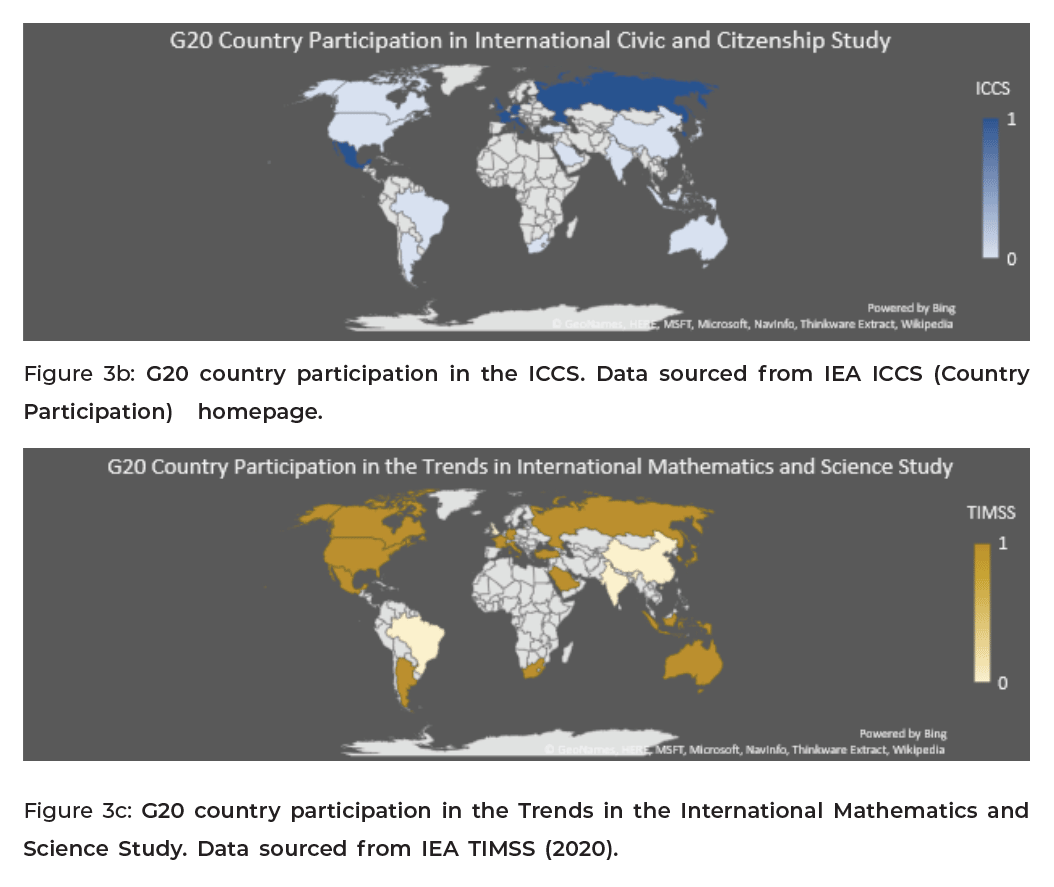

The UNESCO Institute of Statistics conducted a review of four large-scale assessments that had the potential for monitoring progress on thematic indicators 4.7.4 and 4.7.5 and global indicator 4.7.1, in 2019 (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019). The chosen instruments were the International Civic and Citizenship Study (ICCS), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).8 Within this review, the UIS concluded that data sourced from two of these exercises, namely the ICCS and TIMSS, were particularly useful in identifying progress made regarding indicators 4.7.1, 4.7.4, and 4.7.5.

To elaborate, the ICCS provides information on the dispositions, beliefs, knowledge, understanding, and behaviors with respect to civics and citizenship of learners typically in Grade 8 (aged 13.5 years or above). The ICCS study also gathers data from a national context survey that is provided by national research coordinators in participating countries. This national context survey provides rich contextual information (qualitative data) on progress made with respect to global indicator 4.7.1. This includes “curriculum, teacher qualifications and experiences, teaching practices, school environment and climate, and home and community support” (International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, IEA n.d.). Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda (2019) suggested that the TALIS, an OECD instrument that collects data on teachers, school leaders, and the learning environment in schools (OECD 2018a, 2018b), can also provide information on some aspects of ESD-GCED integration within teacher education. However, it is doubtful that this limited dataset on teacher education would warrant its wider deployment across G20 countries.

The UIS review further identified the “ICCS 2016 study as the most comprehensive source of information for the global [sic] indicator SDG 4.7.4” (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019, 11). It noted that information on five of the six key categories could be gleaned from the ICCS dataset for thematic indicator 4.7.4 (namely interconnectedness and global citizenship, gender equality, peace, human rights, and sustainable development). This UIS review process also demonstrated that the PISA 2018 report contained information on the remaining category of “Health and well-being.” The OECD also integrated the assessment of “global competence” within PISA 2018. This included assessing the capacity of 15-year-olds to appreciate differing worldviews, intercultural communication, global mindfulness, engagement in global competence activities, and self-efficacy with respect to global issues (OECD 2018c). The OECD’s framing and motivations for assessment of global competence have faced criticism (Auld and Morris 2019a, 2019b; Engel, Rutkowski, and Thompson 2019). However, the UIS review of PISA 2018 demonstrated that it could contribute data toward monitoring progress made with respect to indicator 4.7.4 across several categories[9] (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019). Therefore, the PISA cannot be discounted as a potential source of data to monitor progress made with respect to indicator 4.7.4. It can provide data relating to the orientation of learners’ mindsets and their perceived competence in relation to certain aspects of global citizenship and sustainability.

For thematic indicator 4.7.5, the UIS proposed that data relating to ESD-GCED outcomes can be gathered from either the PISA or TIMSS (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019). PISA reports provide information on the ability of 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics, and science, and their ability to apply the knowledge gathered to real-life challenges (OECD 2020). Outcomes relating to the environmental science/ sustainability aspect of 4.7.5 are more fully examined in the extended version of science that is implemented in every third cycle; that is, once every nine years (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019). The TIMSS reports provide data in four-year cycles on the mathematics and science achievement of children in Grades 4 and 8 (IEA 2020)—the latter population of mean age 13.5 years being closest to the proposed target learner group of 15-year-olds identified within indicator 4.7.5. The UIS review suggested that TIMSS “offers better conditions for long-term monitoring” than PISA as it gathers similar data on knowledge of environmental science but is deployed at more regular four-year intervals as opposed to the nine-year intervals that PISA (extended science) follows (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019, 17).

Therefore, there is a range of international assessment mechanisms in educational exercises that can be used to monitor progress made with respect to global indicator 4.7.1, and thematic indicators 4.7.4 and 4.7.5. However, research suggests that the 1974 Recommendation, ICCS, and TIMSS are particularly beneficial in this regard (UIS and GAML 2017; Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019; UNESCO 2019a). The challenge for G20 countries is that participation rates across all the aforementioned international assessment exercises vary considerably within the G20 partnership. The low G20 participation rate of just nine countries within the consultation for the 1974 Recommendation (Figure 3a) is concerning given that it has been foregrounded within the approved methodology for assessing global indicator 4.7.1 (UNESCO 2019b). The low participation rate of just seven G20 countries with the ICCS (Figure 3b) will impact additional contextual data collection for thematic indicator 4.7.1 and assessing student attainment for thematic indicator 4.7.4. However, the participation rate of 15 G20 countries in the TIMSS (Figure 3c) is at a reasonable level, which suggests that this instrument can be used within the proposed framework/s for monitoring progress made with respect to thematic indicator 4.7.5.[10] Finally, it is important to note that the timing of these surveys (see Figure A3 in the Appendix) will also affect the monitoring and reporting on progress vis-à-vis Target 4.7 and must be considered while developing frameworks.

Some information on the infrastructure for ESD-GCED integration in tertiary contexts can be gleaned from the consultation on the 1974 Recommendation (UNESCO 2016, 2018b), and the UIS Survey of Formal Education11 (UIS 2016, 2018b, 2020). However, neither instrument gathers information on the proficiency or actions of tertiary students vis-à-vis sustainability or global citizenship. Therefore, there are no internationally validated instruments or reliable sources of qualitative data that are centrally available at the national level to monitor progress vis-à-vis fostering ESD-GCED competencies and actions taken by tertiary students toward sustainability.

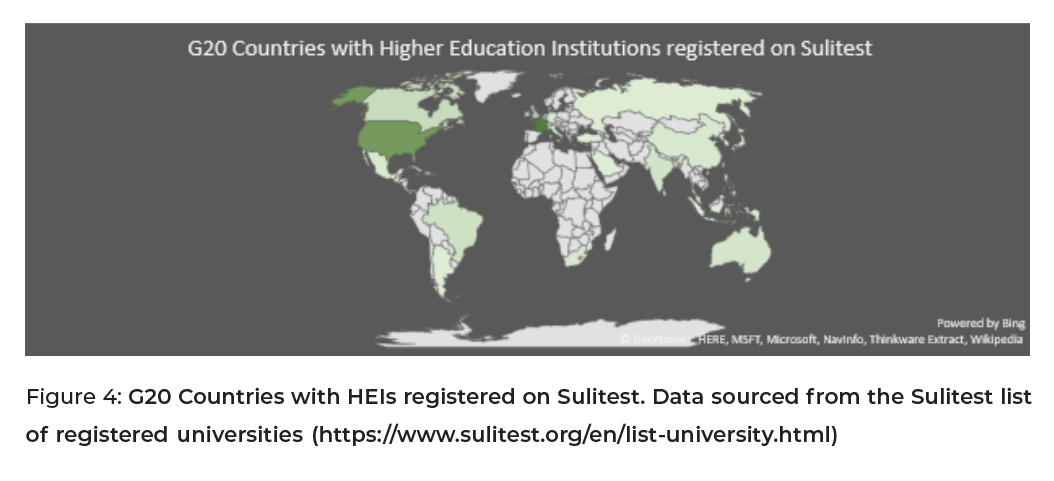

A possible partial solution to this is the Sustainability Literacy Test (Sulitest).12 The Sulitest is an online training and assessment platform (available in eight languages) that can be used by higher education institutions (HEIs) and organizations to support and assess the sustainability literacy of their students. The Sulitest includes modules that raise awareness on key sustainability issues and covers thematic areas related to the SDGs under Agenda 2030 (Decamps 2017). The Sulitest platform can enable learning about sustainability, the discovery of areas of specialization under the ambit of sustainability, and the examination of sustainability knowledge (Decamps 2017). The Sulitest could potentially be used within institutions to monitor progress in ESDGCED integration for global indicator 4.7.1, by benchmarking students’ performance on entry, during, and after exiting the programs of study (Teigen 2018). It also could be used to measure student achievement in terms of their level of sustainability literacy for thematic indicator 4.7.4. While the emphasis in the baseline Sulitest survey is on examining knowledge vis-à-vis sustainability, the customization option can enable HEIs to include additional measures to evaluate student action for sustainability. HEIs in 18 G20 countries currently participate in the Sulitest program (with a median participation level of 10 HEIs, and participation ranging from 1 to over 200 HEIs across the participating countries; Figure 4).

Using the Sulitest platform for monitoring progress in relation to Target 4.7 is not without limitations and challenges. Within the Sulitest, there is an emphasis on examining the knowledge dimension of sustainability in the core module. Merely having an awareness of sustainability, does not guarantee a change in behavior or even a willingness to engage in sustainability-oriented action (Decamps 2017). Therefore, there is a need to include behavioral items as “indicators for possible future sustainability engagement” within the Sulitest’s bank of questions (Mason 2019). A secondary challenge is that sustainability specialists are necessary for the customization and localization of the Sulitest bank of questions in particular disciplinary areas or to address local contexts (Teigen 2018). While access to some elements of the Sulitest is free for HEIs, an annual subscription fee is charged if, for example, question items are customized to examine students’ actions, or for access to other premium services. Finally, according to Mason (2019), the length of the Sulitest can be a matter of concern, particularly if customized module question items are added to the standard question items.

This policy brief began with a recognition of the need to develop holistic frameworks for mapping progress in ESD-GCED implementation at all levels of education. Within the aforementioned large-scale international surveys (that are mainly applicable in primary or post-primary education contexts), the assessment of learners’ values, attitudes, dispositions, and actions toward sustainability and global citizenship is limited. Furthermore, there is limited information on qualitative processes that can be integrated to monitor ESD-GCED progress on Target 4.7 effectively. This calls for an exploration of appropriate quantitative and qualitative assessment processes by G20 partners, which can contribute toward the quality monitoring of progress vis-à-vis ESD-GCED. The following recommendations propose structures that can bring together relevant experts and stakeholders to discuss and arrive at a consensus on appropriate qualitative and quantitative measures. These will further inform assessment frameworks that can be used to map progress in terms of ESD-GCED integration and implementation within G20 countries holistically.

Policy Recommendations

This policy brief recommends the implementation of the following G20 Collaborative Strategy in order to accelerate the monitoring of progress made toward achieving Target 4.7 of SDG 4 in the G20 countries. This collaborative strategy will seek to increase the capacity of the G20 countries to holistically assess progress made in the implementation of ESD-GCED across all levels of formal education.

Recommendation 1: Formulation of a G20 Collaborative Strategy

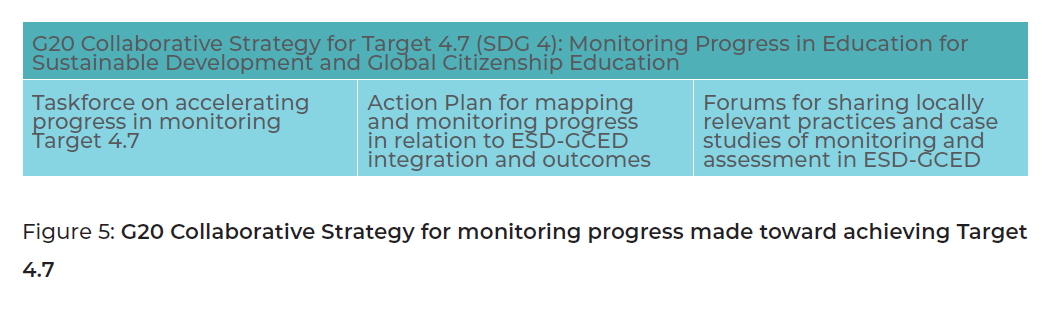

The first recommendation is to formulate the G20 Collaborative Strategy (Figure 5), and the first dimension of this strategy involves the establishment of a Taskforce to examine and advise on ways to improve progress in monitoring ESD-GCED imple-

mentation across all levels of education, specifically in relation to indicators 4.7.1, 4.7.3, 4.7.4, and 4.7.5 under Target 4.7. The Taskforce is responsible for implementing two bodies of work. First, the development of an Action Plan for mapping and monitoring progress on ESD-GCED. Second, the creation of structures that enable the hosting of regular forums for sharing good practices and case studies vis-à-vis assessing the mainstreaming of ESD-GCED and learners’ competencies in sustainability and global citizenship, both within and across G20 countries.

Recommendation 2: Taskforce on accelerating progress in monitoring Target 4.7

The second recommendation is a Taskforce to accelerate progress in monitoring Target 4.7 of SDG 4. The main function of the Taskforce will be to set in place structures that enable the development and implementation of holistic monitoring and evaluation framework/s for ESD-GCED implementation in G20 countries. Specifically, the Taskforce will consider measures that advance monitoring of global indicator 4.7.1, and thematic indicators 4.7.3, 4.7.4, and 4.7.5. The Taskforce will ultimately produce a report for the G20 leadership detailing assessment measures that are suitable for monitoring progress in ESD-GCED implementation in national education policies, curricula, assessments, teacher education programs, and related learning outcomes and actions.

The Taskforce will be steered by a group of experts and policymakers in education and related areas from across the G20 partnership.[13] The scope of the Taskforce includes the implementation of two core activities of the G20 Collaborative Strategy, namely the aforementioned Action Plan and Forums for monitoring ESD-GCED. The Taskforce will oversee a network of processes to facilitate sharing of experiences, including successes, challenges, and lessons learned from evaluation and assessment strategies used to track progress relating to Target 4.7. Kunda Marron and Naughton (2019, 7) noted that assessment is “a political phenomenon that reflects the agendas, tensions, and nature of power relations between political actors.” It is therefore critical that the proposed G20 Collaborative Strategy has the support of governments across the G20 partnership, as well as a broad range of stakeholders. The Taskforce will seek to enhance the quality of decision making and guidance on monitoring and assessment of ESD-GCED through consultations across a range of sectors and agencies. These include the government, the education and training sector, policymakers, practitioners, public broadcasting media (e.g., television and radio), commerce, industry, telecommunications, civil society, non-governmental organizations, parents, and representatives for marginalized and vulnerable groups. The Taskforce will, through participative and consultative exercises with this broad range of stakeholders, also implement an Action Plan for mapping and monitoring ongoing ESD-GCED integration and learning outcomes at all levels of education in the G20 countries. The Taskforce will put structures in place to host a series of forums where policymakers, leaders, researchers, and practitioners can share and discuss case studies of good practices vis-à-vis the assessment and monitoring of ESD-GCED processes, practices, and outcomes. Finally, the Taskforce will advise on and allocate financial and other support necessary for implementing the aforementioned activities.

Recommendation 3: Action Plan for mapping and monitoring progress in relation to ESD-GCED integration and outcomes

The third recommendation is the design and implementation of an Action Plan for mapping and monitoring ESD-GCED integration and outcomes. This will result in the identification of quality assessment processes that can be used to scale up the monitoring of progress on Target 4.7, specifically in relation to global indicator 4.7.1 and thematic indicators 4.7.3, 4.7.4, and 4.7.5 under Target 4.7. The Taskforce will implement the following activities within the Action Plan:

- Conduct a preliminary mapping exercise to build sample national profiles vis-à-vis performance in ESD-GCED integration and outcomes (aligned with indicators under Target 4.7). Data extracted from international assessments in education and qualitative data gleaned from a review of academic literature and reports will be used in this process.

- Commission a review of academic literature and reports across G20 countries to identify qualitative and quantitative measures being used to assess the translation of ESD-GCED policy into practice and local innovations in assessing ESD-GCED integration across education and community contexts in partner countries.

- Conduct a review of the nature and quality of data[14] that can be extracted from these measures with respect to the integration of sustainability and global citizenship within national education policies, curricula, teacher education, learning assessments, and performance outcomes relating to the indicators mentioned above for Target 4.7. The review will also ensure the examination of any gender-related impacts.

- Examine the suitability and feasibility of scaling-up engagements by G20 countries in future international large-scale and local assessments in education exercises. Commission case studies of local ESD-GCED assessment innovations that have the potential to contribute to the monitoring of progress on indicators 4.7.1, 4.7.3, 4.7.4, and 4.7.5.

- Conduct a review of the resourcing required and the willingness of G20 countries to engage in assessments that have the potential to provide data relating to Target 4.7. For example, the consultation on the 1974 Recommendation, WPHRE, ICCS, TIMSS, PISA, and Sulitest discussed in this policy brief, or other unexplored assessments, such as the World Values Survey.15

- Collate and commission case studies in target G20 countries to explore innovative means of identifying and collating data on the translation of the ESDGCED policy into practice, learner performance outcomes, and learners’ actions for ESD-GCED within and beyond educational institutions. Case studies can be gathered through existing ESD-GCED networks, such as the Global Regional Centres of Expertise on ESD (RCE) network16 or the UN Principles of Responsible Management Education network.17

Recommendation 4: Forums for sharing locally relevant practices and case studies of monitoring and assessment in ESD-GCED

The fourth recommendation is the establishment of online and face-to-face forums for sharing locally relevant practices and case studies of monitoring and assessment within ESD-GCED. A key function of the Taskforce will be to create an enabling environment for sharing assessment practices and case studies of successful ESD-GCED integration across the G20 partnership. These actions will allow for collective reflection and decision-making on quantitative and qualitative measures that work best for monitoring ESD-GCED in individual countries within the G20 partnership. They will inform frameworks for monitoring progress made toward achieving Target 4.7. The Taskforce will put in place structures that bring together representatives from high-level and grassroots agencies, as follows:

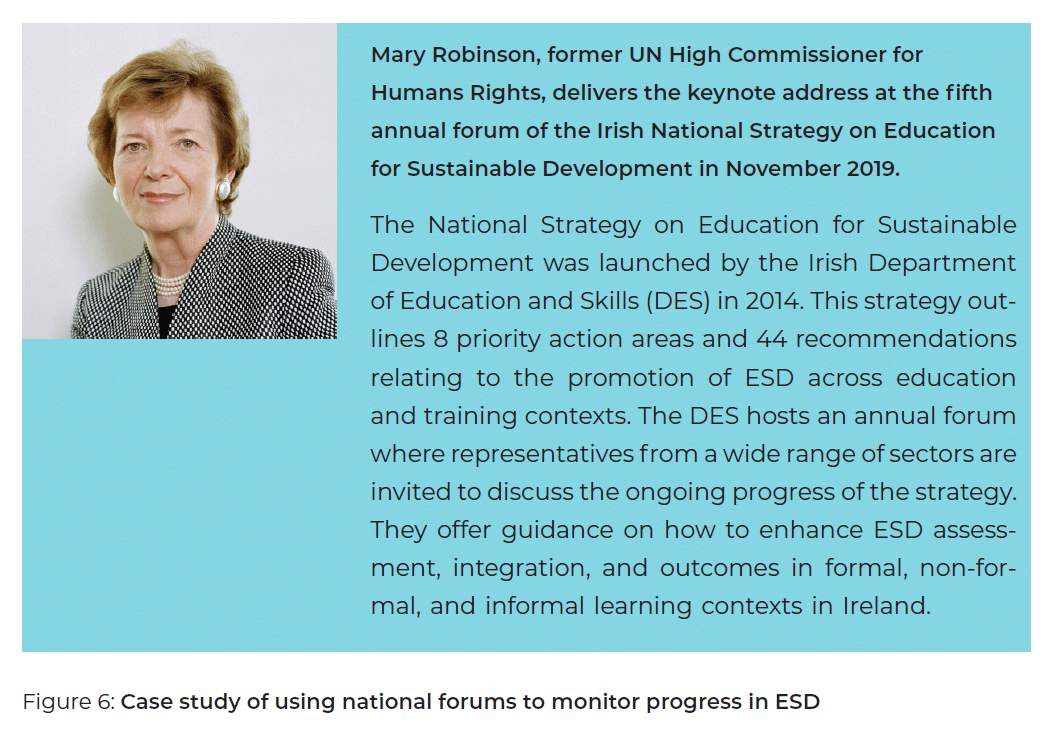

- Establishment of a high-level G20 Education Forum to be attended by policymakers, leaders, and practitioners in education and related areas to share innovative means of monitoring national progress in ESD-GCED integration and outcomes. A good example is the annual forum to monitor the progress of the Irish National Strategy on ESD (Figure 6).

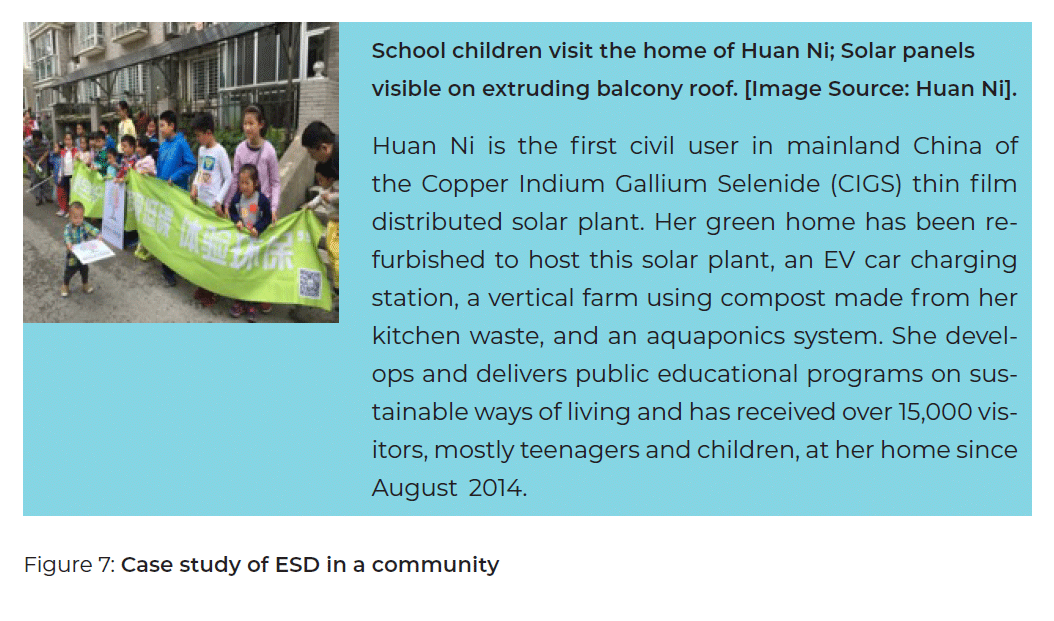

- Host a series of online forums where educators and other stakeholders share knowledge, successful practices, and case studies that can inform innovative performance measures. These include those that capture learning-in-action from successful ESD-GCED practices within and beyond educational institutions, such as the case study of ESD in a community (Figure 7).

- Create an Online Commons through which resources and sample practices for assessing and monitoring progress on the ESD-GCED integration and outcomes for Target 4.7 can be shared and reviewed by policymakers and practitioners. This platform will provide important information on local assessment practices. Through values-based approaches to indicator development, this can be used to generate locally valid indicators of progress on Target 4.7 (Kunda Marron and Naughton 2019). Benavot (2019) suggested that organizations such as the UNESCO may have an important role to play in mediating the review process of such repositories. The quantification and systematic assessment of ESD-GCED integration fall within their scope. The case study of Portugal below describes an innovative way in which online platforms and forums have been activated for the assessment of inclusion in action at the national level.

“The government created a national coordination structure, not to monitor learning outcomes directly but to assess how schools internalized their increased autonomy in curricular development, teaching strategies and allocation of time to subjects, and how schools dealt with the inclusion of all children, especially those with disabilities. As part of the two-year process of curricular development, dissemination activities included an online platform with education resources and curricular guidelines. School visits and invitations for model (or ‘lighthouse’) schools to present their practices to other schools also promoted reflection.”

(Extract from the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report, 2019c, 32–33)

Recommendation 5: Policy brief on life skills-based HIV, and sexuality education

As mentioned in the opening section, a discussion on thematic indicator 4.7.2, which is a measure of progress in relation to the integration of life skills-based HIV and sexuality education, has not been included in this brief. The UIS collects data from governments and heads of educational institutions on the integration of life skills-based HIV and sexuality education within the Survey of Formal Education.[18] Very few G20 countries are participating in the 2020 Survey of Formal Education,[19] which means that progress concerning this indicator will be monitored to a limited extent in the G20 partnership. This motivated the fifth recommendation: The development of a separate policy brief to investigate structures that can enable the monitoring of the integration of life skills-based HIV and sexuality education within school systems across the G20 partnership.

Recommendation 6: Guidance on advancing ESD-GCED infusion at all education levels

It is beyond the scope of this brief to engage in a discussion or analysis of ESD-GCED pedagogical practices and integration processes. Therefore, the sixth and final recommendation is the development of an additional policy brief that makes recommendations on what is necessary to enhance the inclusive nature of ESD-GCED at all levels of education in G20 countries. It should also respond to any issues in implementing ESD-GCED, as identified within the mapping and monitoring processes addressed in this brief.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Akkari, Abdeljalil, and Kathrine Maleq. 2019. “Global Citizenship: Buzzword or New

Instrument for Educational Change?” Europe’s Journal of Psychology 15, no. 2 (May):

176–82.

Auld, Euan, and Paul Morris. 2019a. “Science by Streetlight and the OECD’s Measure

of Global Competence: A New Yardstick for Internationalization?” Policy Futures in

Education 17, no. 6 (January): 677–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318819246.

Auld, Euan, and Paul Morris. 2019b. “The OECD’s Assessment of Global Competence:

Measuring and Making Global Elites.” In The Machinery of School Internationalization

in Action: Beyond the Established Boundaries, edited by Laura C. Engel, Claire

Maxwell, and Miri Yemini, New York: Routledge.

Benavot, Aaron. 2019. “The Past and Future of SDG 4.7.” FreshEd #141: The FreshEd

Podcast. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/freshed-podcast/freshed-141-the-past-and.

Decamps, Aurélien. 2017. “Analysis of Determinants of a Measure of Sustainability

Literacy.” UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report. Accessed June 24, 2020.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259581.

Dill, Jeffrey, S. 2012. “The Moral Education of Global Citizens.” Society 49, no. 6 (October):

541–46.

Dill, Jeffrey S. 2013. The Longings and Limits of Global Citizenship Education: The

Modern Pedagogy of Schooling in a Cosmopolitan Age. New York: Routledge.

Dower, Nigel, and John Williams. 2016. Global Citizenship: A Critical Introduction.

New York: Routledge.

Engel, Laura C., David Rutkowski, and Greg Thompson. 2019. “Toward an International

Measure of Global Competence? A Critical Look at the PISA 2018 Framework.”

Globalisation, Societies, and Education 17, no. 2 (July): 117–31. https://doi:10.1080/14767724.2019.1642183.

Goren, Heela, Miri Yemini, Claire Maxwell, and Efrat Blumenfeld-Lieberthal. 2020.

““Terminological “Communities”: A Conceptual Mapping of Scholarship Identified

with Education’s “Global Turn.”” Review of Research in Education 44, no. 1 (March):

36–63.

Higher Education Sustainability Initiative, HESI. 2019. “Raising and Mapping Awareness

of the Global Goals.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.sulitest.org/hlpf2019report.pdf.

Hellberg, Sofie, and Beniamin Knutsson. 2016. “Sustaining the Life-Chance Divide?

Education for Sustainable Development and the Global Biopolitical Regime.” Critical

Studies in Education 59, no. 1 (April): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1176064.

Holfelder, Anne-Katrin. 2019. “Towards a Sustainable Future with Education?” Sustainability

Science 14, no. 4 (May): 943–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00682-z.

Huckle, John, and Arjen E. J. Wals. 2015. “The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable

Development: Business as Usual in the End.” Environmental Education Research 21,

no. 3 (March): 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1011084.

International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, IEA. No

date. “ICCS International Civic and Citizenship Education Study.” Accessed June 24,

2020. https://www.iea.nl/studies/iea/iccs.

International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, IEA. 2020.

“Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. TIMSS Participating Countries.”

Accessed June 24, 2020. https://nces.ed.gov/timss/countries.asp.

Istance, David, Anthony Mackay, and Rebecca Winthrop. 2019. “Measuring Transformational

Pedagogies Across G20 Countries to Achieve Breakthrough Learning:

The Case for Collaboration.” Accessed June 20, 2020. https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-measuring-pedagogies-g20-countries-achive-learning.

Jickling, Bob, and Arjen E. J. Wals. 2008. “Globalization and Environmental Education:

Looking beyond Sustainable Development.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 40,

no. 1 (January): 1–21. https://doi:10.1080/00220270701684667.

Kunda Marron, Rosaria, and Naughton, Deirdre. 2019. “Using Learning Assessment

Data to Monitor Progress for SDG target 4.7.” Bridge 47 – Building Global Citizenship.

Accessed June 24, 2020. https://bridge47.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/using_learning_assessment_data_to_monitor_progress_for_sdg_target_4.7_0.pdf.

Mason, Alicia, M. 2019. “Sulitest ®: A Mixed-Method, Pilot Study of Assessments Impacts

on Undergraduate Sustainability-related Learning and Motivation.” The Journal

of Sustainability Education 20, (April 2019). Accessed June 15, 2020. http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/sulitest-a-mixed-method-pilot-study-of-assessment-impacts-on-undergraduate-sustainability-related-learning-and-motivation_2019_05.

Morris, Paul. 2016. Education Policy, Cross-national Tests of Pupil Achievement, and

the Pursuit of World-class Schooling: A Critical Analysis. London: UCL Institute of

Education Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD. 2018a. “TALIS

2018 Country Notes.” Accessed June 24, 2020. http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis-2018-country-notes.htm.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2018b. “TALIS 2018

Technical Report.” Accessed June 24, 2020. http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS_2018_Technical_Report.pdf.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2018c. “Questions Relating

to Global Competence in the Student Questionnaire.” Accessed June 24, 2020.

https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA-2018-Global-Competence-Questionnaire.pdf.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2020. “PISA Programme

for International Student Assessment. Participants.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/aboutpisa/pisa-participants.htm.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2017. “Second

Phase (2010–2014) of the World Programme for Human Rights Education.” Accessed

June 24, 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/WPHRE/Third-Phase/Pages/ProgressReport3rdPhase.aspx.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2017. “Midterm

Progress Report on the Implementation of the Third Phase of the World Programme

for Human Rights Education.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/WPHRE/ThirdPhase/Pages/ProgressReport3rd-Phase.aspx.

Pashby, Karen. 2015. “Conflations, Possibilities, and Foreclosures: Global Citizenship

Education in a Multicultural Context.” Curriculum Inquiry 45, no. 4 (October): 345–

366. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2015.1064304.

Paul, Delia. 2018. “Education 2030 Committee Issues Recommendations on SDG 4.”

Accessed June 24, 2020. https://sdg.iisd.org/news/education-2030-committee-issues-recommendations-on-sdg-4.

RCE Network. n.d. “Global RCE network in Education for Sustainable Development.”

Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.rcenetwork.org/portal.

Sandoval-Hernández, Andrés, Maria Magdalena Isac, and Daniel Miranda. 2019.

“Measurement Strategy for SDG Global Indicator 4.7.1 and Thematic Indicators 4.7.4

and 4.7.5 using International Large-Scale Assessments in Education.” GAML6/REF/9.

Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Accessed June 24, 2020. http://gaml.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/08/GAML6-REF-9-measurement-strategy-for-4.7.1-4.7.4-4.7.5.pdf.

Sharma, Namrata. 2018. Value-creating Global Citizenship Education: Engaging

Gandhi, Makiguchi, and Ikeda as Examples. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sharma, Namrata. 2020. “Integrating Asian perspectives within the UNESCO-led Discourse

and Practice of Global Citizenship Education: Taking Gandhi and Ikeda as

Examples.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning, edited

by Douglas Bourn, 90–102. England: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sjögren, Hanna. 2019. “More of the Same: A Critical Analysis of the Formations of

Teacher Students through Education for Sustainable Development.” Environmental

Education Research 25, no. 11 (October): 1620–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1675595.

Sousa, Diana, Sue Grey, and Laura Oxley. 2019. “Comparative International Testing of

Early Childhood Education: The Democratic Deficit and the Case of Portugal.” Policy

Futures in Education 17, no. 1 (January): 41–58.

Sustainability Literacy Test. n.d. “Sulitest.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.sulitest.org/en/index.html.

Teigen, Charlotte, S.E. 2018. “Application of the Sustainability Literacy Test at NTNU

– A study on Integration of the SULITEST as Tool for Learning and Testing Sustainability

Literacy.” Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Accessed June 30, 2020. https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2578671/18741_FULLTEXT.pdf?sequence=1.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, UNESCO. 2014.

“UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education

for Sustainable Development.” Accessed June 24, 2020. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002305/230514e.pdf.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2015a. “Global Citizenship

Education: Topics and Learning Objectives.” Paris, France. Accessed June

24, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232993.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2016. “UNESCO

1974 Recommendation Used to Measure Progress Towards Education Target 4.7.”

Accessed June 24, 2020. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/media-services/single-view/news/unesco_1974_recommendation_used_to_measure_progress_towards/.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2018a. Global Citizenship

Education: Taking it Local. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2018b. “Progress

on Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship Education. Findings

of the 6th Consultation on the Implementation of the 1974 Recommendation

Concerning Education for International Understanding, Co-operation and Peace

and Education Relating to Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (2012–2016).”

Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/

180320eng.pdf.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2018c. “SDG-Education

2030 Steering Committee Meeting: Synthesis of Key Recommendations

– March 2018.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.sdg4education2030.org/sdg-education-2030-steering-committee-meeting-synthesis-key-recommendations-march-2018.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2019a. “SDG – Education

2030. Part II. Education for Sustainable Development Beyond 2019.” 206 EX/6.

II. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366797.locale=en.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2019b. “A Stepping

Stone Towards Measuring Progress Towards SDG 4.7.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://en.unesco.org/news/stepping-stone-towards-measuring-progress-towards-sdg-47.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2019c. “Beyond

Commitments: How Countries Implement SDG 4.” Prepared by the Global Education

Monitoring Report team. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000369008.

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2019d. “Educational

Content Up Close. Examining the Learning Dimensions of Education for Sustainable

Development and Global Citizenship Education.” Accessed June 20, 2020.

https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/200004eng.pdf.

United Nations General Assembly, UNGA. 2004. “59/113. World Programme for Human

Rights Education.” Accessed June 15, 2020. https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/59/113.

United Nations General Assembly. 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda

for Sustainable Development.” A/RES/70/1. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E.

United Nations Global Compact. n.d. Principles for Responsible Management Education.

Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.unprme.org.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics, UIS. 2016. “Instruction Manual: Survey of Formal Education.”

Accessed June 24, 2020. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/uis_ed_m_2016_0.pdf.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2018a. “Quick Guide to Education Indicators for

SDG4. UNESCO Institute for Statistics.” Quebec, Canada. Accessed June 24, 2020.

http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/quick-guide-education-indicators-sdg4-2018-en.pdf.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2018b. “Instructional Manual: Survey of Formal Education.”

Montreal, Canada. October 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/instruction-manual-survey-formal-education-2017-en.pdf.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2018c. “Request to Upgrade to Tier II Global Indicator

4.7.1 and 12.8.1.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/meetings/webex-13dec2018/1_4.7.1_12.8.1_Tier%20reclassification%20request_UNESCO.pdf.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2018d. “TCG4: Development of SDG Thematic Indicator

4.7.2.” Accessed June 15, 2020. http://tcg.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/08/TCG4-17-Development-of-Indicator-4.7.2.pdf.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2020. “UIS Questionnaires-2020 Survey of Formal Education.”

Accessed June 24, 2020. http://uis.unesco.org/uis-questionnaires.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics and Global Alliance for Monitoring Learning. 2017.

“Measurement Strategy for SDG Target 4.7: Proposal by GAML Task Force 4.7.”

Global Alliance for Monitoring Learning. Fourth meeting 28–29 November 2017, Madrid,

Spain. Accessed June 24, 2020. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/gaml4-measurement-strategy-sdg-target4.7.pdf.

World Values Survey. n.d. “WVS Contents.” Accessed June 24, 2020. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp.

Appendix

[1] . SDG 4: Target 4.7: “By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (United Nations General Assembly 2015, 17).

[2] . ESD “empowers learners to take informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability and a just society, for present and future generations, while respecting cultural diversity” (UNESCO 2014, 12).

[3] . GCED aims to “empower learners of all ages to assume active roles, both locally and globally, in building more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive and secure societies” (UNESCO 2019d, 10), and “emphasizes political, economic, social and cultural interdependence and interconnectedness between the local, the national and the global” (UNESCO 2015, 14).

[4]. The instruments in Figure 2 are mainly large-scale international assessment exercises that gather data typically at the national level, with the exception of the Sulitest, which facilitates local data collection by individual higher education institutions (HEIs).

[5]. The United Nations Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG indicators formally approved the methodology for measuring progress on indicator 4.7.1, which foregrounds the 1974 Recommendation consultative process (UNESCO 2019b).

[6]. UN General Assembly resolution 59/113 A.

[7]. To date, data from ten G20 countries have been gathered across the second and third World Programme on Human Rights Education surveys through the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The data sources for:

• Second WPHRE – https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/WPHRE/SecondPhase/Pages/Secondphaseindex.aspx

• Third WPHRE – https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/WPHRE/ThirdPhase/Pages/ProgressReport3rdPhase.aspx

[8]. The ICCS and TIMSS surveys are deployed by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), and the TALIS and PISA surveys are deployed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

[9] . The UIS review demonstrates that PISA 2018 could contribute data for thematic indicator 4.7.4 on three thematic areas: interconnectedness and global citizenship, health and well-being, and sustainable development, but not in the thematic areas of peace, non-violence and human security, gender equality, and human rights (Sandoval-Hernández, Isac, and Miranda 2019).

[10] . Charts relating to G20 country participation in PISA (Figure A1) and TALIS (Figure A2) have been included in the Appendix.

[11] . The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) Survey of Formal Education has been extended to collect data that can be used to “monitor and report on international development goals related to education, including the education goal of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (UIS 2016, 4).

[12] . The Sulitest emerged from the Higher Education Sustainability Initiative (HESI) in 2012 and has the support of a broad range of bodies within and beyond the United Nations. The Sulitest can be used by HEIs to assess sustainability literacy levels. The Sulitest Organisation is a non-profit. It has received financial support from a range of sources, including corporate organizations.

[13] . This policy brief builds on the recommendation of the T20 policy brief submitted by David Istance, Anthony Mackay, and Rebecca Winthrop (2019), on “Measuring Transformational pedagogies across G20 countries to achieve breakthrough learning: The case for collaboration.” They recommended that the G20 establish a Taskforce comprising leading thinkers from the G20 and around the globe to develop these shared measures.

[14] . A systematic methodological approach and specialized tools will be needed for analysis of these large datasets, such as those used by Goren, Yemini, Maxwell, and Blumenfeld-Lieberthal (2020).

[15] . The World Values Survey seeks to help scientists and policymakers understand changes in the beliefs, values, and motivations of people worldwide, and can potentially contribute toward monitoring progress on the global citizenship dimension of indicator 4.7.4. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp

[16] . The Global RCE network has over 170 Regional Centres of Expertise involved in ESD at various levels of education. https://www.rcenetwork.org/portal

[17] . The Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME) is a UN-supported initiative founded in 2007 to raise the profile of sustainability in higher education. https://www.unprme.org

[18] . The UIS initially piloted questions and collected information on the integration of sexual and reproductive health education in formal curricula in their annual Survey of Formal Education in 2017. It re-framed this subsection to include generic life skills and HIV prevention in 2018, which since then has been titled “Life skills-based HIV and sexuality education” (UIS 2018d).

[19] . Data on country participation in the 2020 Survey of Formal Education was sourced from http://uis.unesco.org/uis-questionnaires.